Enshrinees different, but alike

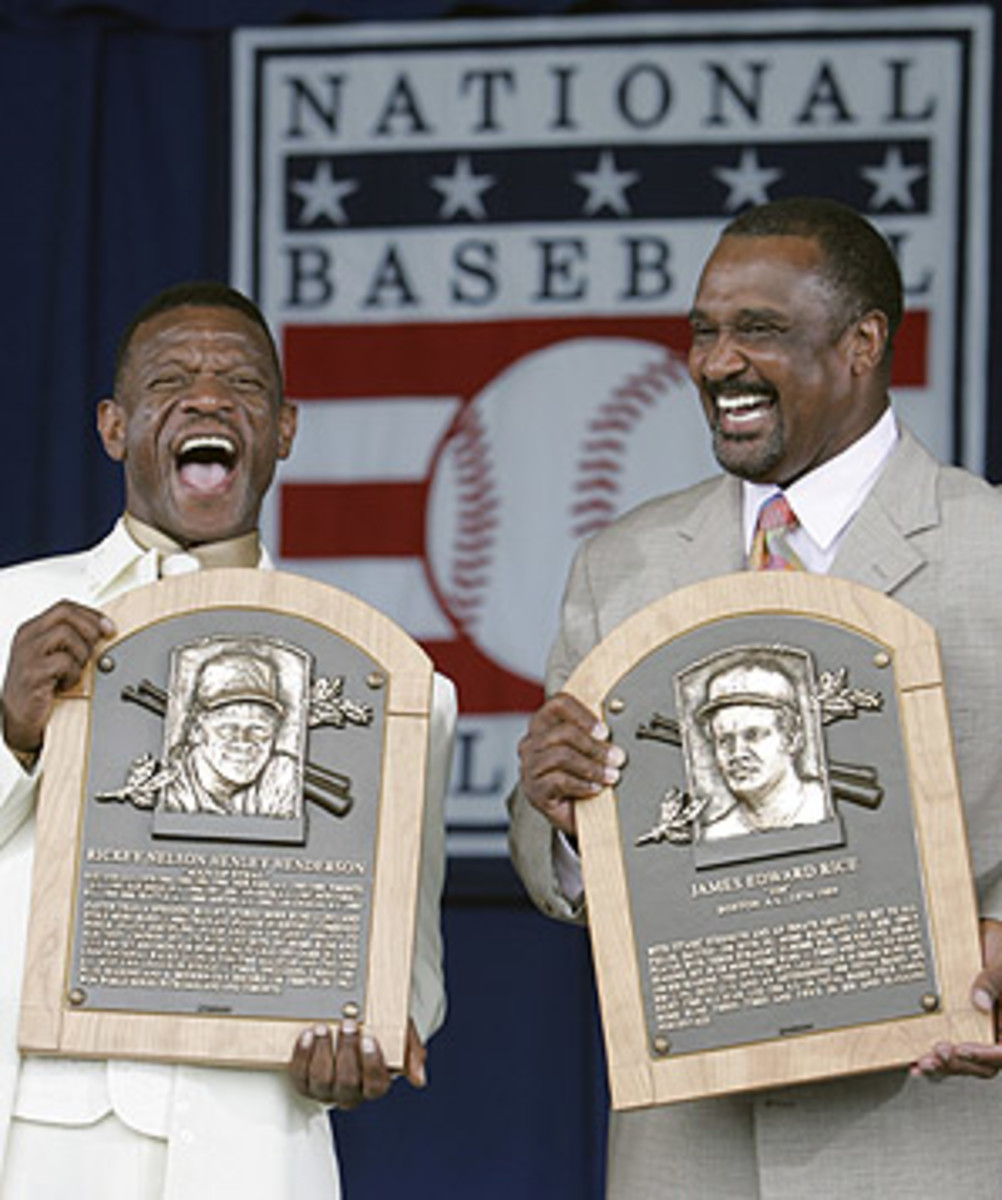

Yet for the two men who made up the core of the Hall Class of 2009, when it came to the playing careers that were being immortalized Sunday, they could not have been more different.

Henderson was a thief, a speed demon who literally stole his way into the hearts of fans across the country, while suiting up for nine different teams. Rice was a power hitter, a menacing presence in the batter's box who starred for just a single team. Henderson was a starring member of two World Series winning teams while Rice lost the only Fall Classic he appeared in (Rice missed the 1975 World Series due to injury). And while they debuted just a few years apart in the 1970s, Rice's career was over by 1989, while Henderson played another 14 seasons in the majors. Rice said he left the game with no regrets, other than hanging around too long in 1989 and watching his lifetime batting average dip below .300. Henderson, in contrast, talked about the "burning desire" to still play the game and refused to acknowledge that even at 50 years of age, he would be unable to compete in the majors today.

Their personalities, too, are a study in contrasts. Henderson talks fast and thinks even faster, and his winning smile and colorful personality were a large part of his popularity throughout his quarter-century career. He didn't disappoint on Sunday, peppering his speech with laugh lines like when he thanked former A's owner Charlie O. Finley "and that donkey" or when he recalled once asking Reggie Jackson for an autograph as a child in Oakland and getting a pen with Reggie's name on it in return. (Asked later if he'd gotten Jackson's autograph yet, Rickey laughed and said, "No but he's looking for my autograph.") Rice, meanwhile, could be both hard to know and harder to like, even pointing out in his speech the irony that he had battled the press for so many years, and now was one of them, as an analyst on NESN. Their speeches, too, were different. Henderson's was rambling, lengthy and humorous, while Rice's was consistent, concise and serious.

There was one area, however, in which the men and their two careers had quite a bit in common. For baseball fans who prefer their heroes to love the game from their earliest days the way they do, it may come as something of a disappointment, or at least a surprise but neither had their heart set on being a baseball player in the first place and very nearly stopped pursuing the sport altogether.

Of course, judging by the role call of Hall of Famers that kicked off the ceremony, Rice and Henderson were not alone in this regard. Sandy Koufax played basketball in college, as did Dave Winfield, who was drafted by four teams in three different sports. Bob Gibson played basketball for the Harlem Globetrotters one year. Reggie Jackson had a football scholarship to Arizona State. It speaks to the pure athleticism that is required to reach a point where only the best of the best, one percent of all men to have ever played the game at its highest level, are enshrined, but it is also amazing to think that while Henderson and Rice were being celebrated as baseball legends that both had very different goals in mind for their athletic futures when they were younger.

Both men grew up loving football, playing both offense and defense and enjoying the sport's physical nature. Henderson was first caught the attention of college football recruiters after a dominant freshman season where, by his estimation, he "scored 13 or 14 touchdowns and rushed for 1,000 yards." Rice was good enough to be offered a football scholarship to Nebraska, only choosing baseball when his father suggested he had a better chance at a pro career on the diamond rather than the gridiron.

By that point, Rice was also a top baseball prospect, but he may never have even made it that far in his career if not for a local American Legion coach named Owen Sailors. When the summer came after a long school year of studying and sports, more athletic activity was the last thing Rice wanted. "I wanted to get a job and make some money," he said on Sunday. Instead, Sailors began showing up at Rice's home in Anderson, S.C., in an attempt to convince this prodigy that if he worked at the game it could become his job and he would make plenty of money. Sailors was initially rebuffed on his first attempt when Rice's mother told her son it was his choice, and Rice refused. But when he came back the second day, "Mom said you better go play baseball to stop this man from coming by the house," Rice said. "That's what I did. No regrets."

More than 3,000 miles away and a couple of year later, the man who would one day be hailed in Cooperstown by former teammate Dave Stewart as "one of the four or five best players to ever play the game" was also choosing to focus on other pursuits. Henderson preferred football, but his athletic gifts were obvious to all. A guidance counselor at his high school named Mrs. Wilkerson was especially impressed, and in an effort to get the school's best players to try baseball, she offered Henderson a deal: twenty-five cents for every base hit, run scored or stolen base. Henderson accepted, and after amassing 30 hits, 25 runs and 33 stolen bases in his first year soon had a few more dollars in his pocket and a new goal: become a professional baseball player. "She bribed me into playing baseball," Henderson said. "She's the one who got me to play."

Thankfully, there were those who saw something in Rice and Henderson that perhaps they didn't see in themselves and it was those people who put the newest Hall of Famers on the twisting road that ended in Cooperstown on a summer Sunday afternoon. Had they not steered them in that manner, think of what we would have missed. An electrifying base stealer who would break some of the most familiar records in the game's history. A dominating power hitter who set the standard of his era for slugging ability. Without them, the stage in this picturesque village on Sunday, to say nothing of the game they excelled at for so long, would have been very empty.