Last Night on 'The Last Dance': Episodes 1 & 2

If we could conjure up a metaphorical watercooler right now—a place where we gather (observing social distancing of course), grouse and gab—would the word Jordan be on most of our lips? Is there a comparison to be made with a long-ago Monday morning, specifically Feb. 10, 1964? That’s when the national conversation centered on Paul, John, George and Ringo, the previous night’s guests on The Ed Sullivan Show, that program being our national cultural clearinghouse back in those three-channel days.

We will know more when we get ratings from Sunday night’s first two episodes of The Last Dance, the ESPN-Netflix Michael Jordan documentary that will answer the question: With a great majority of us in quarantine, will the already-well-told tale of an athlete who hasn’t played since 2003 serve as our collective conversation piece? Moreover, does The Last Dance have the goods to carry us through eight more hours over the next four Sundays?

My answer to the last query: a definite maybe.

There are a limited number of athletes we would even consider to have a chance at passing the 600-minute litmus test. Muhammad Ali? Sure. Serena and Venus Williams together? Maybe. Tom Brady? Uh … no. Now, Ken Burns gave The Roosevelts 14 hours over seven episodes, but you had three of them to get at, including Eleanor, and two of them were, you know, president. Charlie Pierce, who toggles between sports and politics about as well as anyone, questioned on Twitter why Jordan would even remotely warrant that much time, since he never had much interesting to say about subjects outside of basketball.

A reasonable point. But as someone who covered Jordan for the better portion of his NBA career, I can say: You didn’t go to Jordan to plug into the national zeitgeist. You went to Jordan to chronicle his basketball journeys, to bear witness to his GOAT-ness, to write about this fierce force of nature who never tired of dominating, to try to deconstruct this most-hyped of athletes who somehow always lived up to his hype, a very difficult thing to do. Which is another way of saying: You went to Jordan to watch him play.

Plus, if Jordan was vanilla on politics, he was never an anodyne personality. He could get wound up, and working in the doc’s favor is the fact that Jordan was most wound up before and during the 1997–98 season, which serves as the grounding point for The Last Dance.

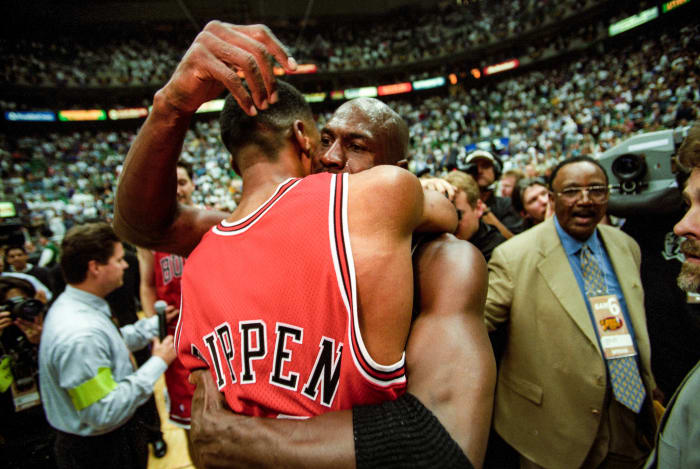

The Bulls were coming off two straight championships, but Scottie Pippen was injured and furious with his contract; Dennis Rodman was a here-today-gone-tomorrow heyoka, in Phil Jackson’s words (a backward-walking man from Native American culture); and management, as if propelled by some mysterious centripetal force that even they didn’t quite understand, was determined to break up the team.

So with an NBA Entertainment camera crew already having been granted unlimited access, coach Jackson—master of aphorism, creator of themed content—termed the ’97-98 season “The Last Dance.”

Phil also liked The Band. We’ll get back to that.

A personal admission. I would be less than honest if I said it didn’t matter to me that I wasn’t interviewed for the doc, though over the years I have pontificated about Jordan and others of his generation on outlets too numerous to count. According to The Last Dance’s producers, 130 subjects were interviewed on camera, so I must’ve been, in the comforting words of former Sports Illustrated colleague Michael Farber, “No. 131, for sure.”

I was scheduled on at least four occasions to talk on camera, but each was called off, one of them because, I was told, “We have to do J.T.”

Holy hell, James Taylor? James Taylor’s in the Jordan doc!? Must be a “Going to Carolina in My Mind” connection with MJ. But, no; the singer-songwriter, is not in the doc. Justin Timberlake, however, is. Among others who make present-day appearances, just in the first two episodes: Barack Obama, William Jefferson Clinton, Larry Bird, Magic Johnson and Isiah Thomas. Ten hours is a big canvas, so you better have a lot of paint.

* * *

Regarding the title, it’s doubtful that Bulls players were fans of Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm and the boys, but in the back of Phil Jackson’s mind was Martin Scorsese’s classic 1978 concert film The Last Waltz, which chronicles the final gig for The Band, which took place two years earlier at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco.

“It was a big takeoff on that movie,” Jackson told me a couple of days ago. “Plus, I did often refer to working the triangle [offense] as being a dance. I taught the players to work on a 4/4 beat, like hip-hop time. I used to say: ‘You have two seconds to assess your position and act. If you hold the ball any longer, you are impeding the offense.’ ” Jackson told me that on many nights assistant coach Tex Winter, one of the architects of the triangle, would nudge him and say, “Take Jordan out. He’s holding the ball too long.” Jackson would usually ignore him.

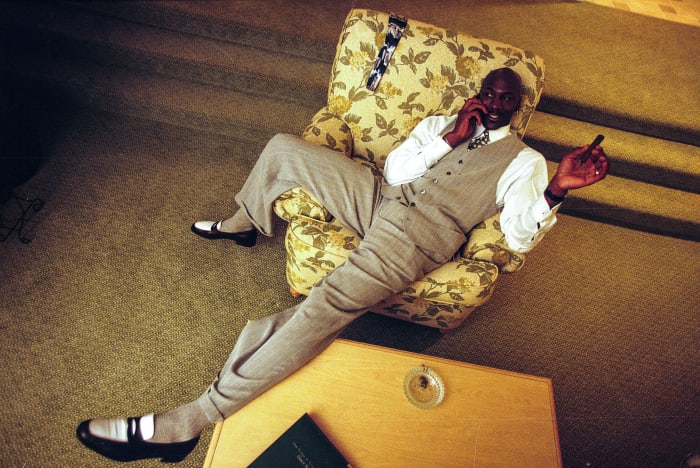

Today’s Jordan first appears in Episode 1 shot from behind—alone; big, bald head gleaming like Ving Rhames’s Marsellus Wallace in Pulp Fiction; left-ear-ringed; sliver-thin Zorro ’stache; expensive watch; staring out of a mansion window onto a cerulean sky and sea. He could be a Central American dictator in exile, which is not a terrible metaphor for Jordan, who surfaces rarely these days and once commanded comparable power and intrigue. One of the best things about the first two hours of The Last Dance is that it appears Jordan is all in, talking comfortably in an easy chair, a glass of something smooth beside him, cigar sometimes in hand.

We don’t stay there long, as director Jason Hehir shifts to the 1997–98 season, and the first thing we hear that version of Jordan say is: “You remember back in 1984, when they drafted Michael Jordan …”

Ah, yes, nobody has ever done third person better than Michael Jordan. Jack McCallum says that no one has ever done third person better than Michael Jordan. MJ sets the theme in that clip from the Bulls’ first game of the season: “We’re five-time champions, going for six, but we need your support.”

The Knicks were no obstacle to Jordan's 1997-98 Bulls, who swept N.Y. in the regular season.

Manny Millan

I wasn’t covering the NBA that season, and over the years I had forgotten how deep the rift was between the team and management, or more specifically between Pippen and general manager Jerry Krause. Jackson came up with the Last Dance theme to accentuate the finality, not to mention the difficulty of the challenge that lie ahead. Rarely does a team with a clear expiration date have the goods to win it all, but the Bulls were that rare team.

If there’s an antihero of the first episode it’s Krause, who died in 2017 at 77, rightfully remembered as the man who both assembled and disassembled the six-time champions. I was around the Bulls a lot during their first threepeat, in the early ’90s, and even back then both Jordan and Pippen could be cruel in their treatment of Krause, a small, socially awkward man whom they called “Crumbs.” Krause’s problem, says owner Jerry Reinsdorf, “was that sometimes he loved people who didn’t love him back, and it would disappoint him.”

By the Last Dance season, Pippen’s ridicule of Krause had turned toxic. The small forward had delayed surgery on his left foot so he could relax during the summer and rehab during the start of the season—“Scottie was wrong in that scenario,” says Jordan—then he planned to demand a trade. Krause had also begun a public friendship/courtship with a young Iowa State coach named Tim Floyd, sending the message that Jackson could easily be replaced as coach, another thing that made Jordan’s and Pippen’s blood boil. Jackson, and only Jackson, was their man.

All that set up the central tension of the 1997–98 season, but the documentary doesn’t stay there. In both Episodes 1 and 2, Hehir executes several successful pivot moves—in the former, back to the execrable pre-Jordan Bulls (where former WGN play-by-play man Bob Costas, with a wonderfully full head of wavy, blondish 1979 hair, makes a cameo); and then to Chapel Hill where, as Tar Heels teammate James Worthy puts it, “I was better than him … for about two weeks.”

When I see this film of Jordan at Carolina, and in the early Chicago days, I think back to covering him in the mid-’80s, and I’m struck at what a kid he was. With the possible exception of Isiah Thomas, no eventually-great player has ever come into the league looking more like a kid than Jordan. Neither Bird nor LeBron ever seemed to be young, and, though Magic was kidlike in his exuberance, there was something CEO-ish about him from the beginning.

Not Jordan. The shot of the Tar Heels freshman pedaling his bike on the Carolina campus with roommate Buzz Peterson is priceless, as is Jordan’s own tale of knocking on hotel doors to find Bulls teammates in the preseason of his rookie year. And when he was finally admitted …

“It was things I had never seen in my life as a young kid,” Jordan says. “You got your [cocaine] lines over here, you got your weed smokers over here, you got your women over here.” Jordan announced to his team: “Look, man. I’m out,” and from that time on, Jordan was on an island of his own.

There was indeed a delicious naivete about him in those early years in the league. Jordan would chuckle in embarrassment when people used the f-word, and it never came out of his mouth easily—again, I’m emphasizing the early days—which made his eventual … let’s call it “withdrawal” all the more stark.

To a large degree, Bird and Magic had the same personality at the end of their careers as they had in the beginning; Jordan did not. He started a kid, and at the end he was a crusty oldster, beaten down by fame and the ravages of his own searing competitiveness.

Jordan the "crusty oldster, beaten down by fame and...his own searing competitiveness."

Walter Iooss Jr.

The second episode begins with Jordan’s eternal No. 2, and it was refreshing to see the hometown of “Scott” Pippen—as he was called by David Stern on draft night, 1987—and watch him dominate at Central Arkansas. I had never seen that footage. Then again, there was so much about Pippen I didn’t see, even when I was covering the team, so completely did Jordan suck up the Windy City oxygen. Pippen talks about his boyhood in Hamburg, Ark., with a father and a brother who were both disabled. “Two people in wheelchairs,” Pippen tells Hehir, who conducted many of the interviews. “Two people in diapers” is how he described it to me for a book I wrote about the 1992 Olympic Dream Team.

In those moments when Pippen talks about his boyhood, you can see the roots of his later dissatisfaction. He had agreed in 1991 to a seven-year $18 million deal, which even Reinsdorf advised him not to sign, aware of how underpaid that would make him in the final years. But Pippen wanted to take care of a family that had endured such a hard, hard road. So he signed, and neither Reinsdorf nor Krause would ever undo that mistake. By ’97, when Pippen was one of the top five players in the league, he was No. 122 in salary. On the Bulls alone, Toni Kukoc, Ron Harper, Rodman and Luc Longley, along with Jordan, all made more money than Pippen.

Episode 2 makes another hard pivot to Jordan’s boyhood, which was certainly easier than Pippen’s, but difficult in its own way. I’ve heard Jordan himself talk many times about the competitive drive of his older brother. “If you think I’m insane,” Jordan told me once, “you should see Larry.” But new to me was this revelation: “I always felt like I was fighting Larry for my father’s attention.”

Indeed, the late James Jordan—“Mister Jordan,” as his widow, Deloris, always refers to him—haunts the second episode, knowing, as we do, that in the summer of 1993, not that long after the documentary interviews took place, he will end up a murder victim. I saw Michael and his dad together many times and figured that Michael had always been the chosen one, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. James Jordan was a DIY kind of guy, and so was Larry, but Michael was not. Michael was more the mama’s boy, as James saw it, and from time to time told his son so. Jordan’s father was a harder man than I realized, and that had a lot to do with Jordan’s becoming a maniacal competitor.

By the time we see Jordan recover from his second-season broken ankle, get his storied back-to-back 49 and 63 points against the Celtics in the 1986 playoffs, then pivot again back to ’97, the trail of the doc is clear: The central story will be the Last Dance season, but there are dozens of possible cutaways and always something there to remind me (Dionne Warwick, ’63) of Jordan’s greatness as a player.

Somehow, the other questions about Jordan, his refusal to dip his toe into controversy, the “Republicans buy sneakers too” comment (I’m going to let the documentary straighten that out, because I never heard him directly say that) melt away. Do I wish that in 1990 he had endorsed the Senate candidacy of Harvey Gantt, a black man running against the race-baiting, “Dixie”-whistling anachronism known as Jesse Helms? Of course. Maybe Jordan’s reluctance to get involved in politics will be discussed, and perhaps rationalized away, later.

But, honestly? To see Jordan in any other arena besides a sporting one is not why most of us tuned in, nor will it be what most of us discuss at our metaphorical watercooler. See you next Monday.

Jack McCallum covered Jordan for years as an SI senior writer and remains a special contributor to the magazine. The author of the New York Times bestseller Dream Team, he is the narrator of the upcoming podcast The Dream Team Tapes, due out May 17. Subscribe here.