Range of emotions

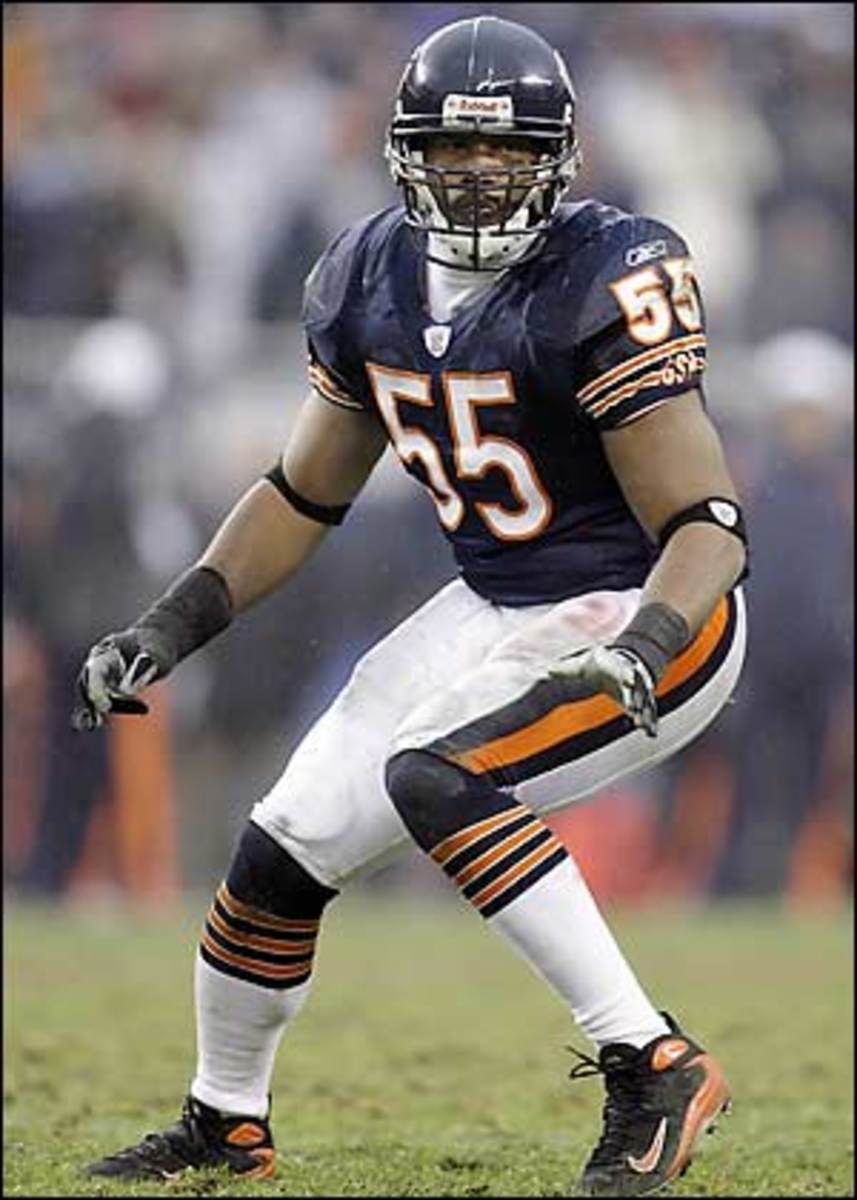

The NFL's free agency period begins Thursday at midnight and most fans have a wish-list of players they'd love to see their team acquire. Unlike the draft, which is vastly more speculative, free agency is really the only time to secure proven NFL commodities like cornerback Asante Samuel and linebacker Lance Briggs, two of the biggest names in this year's crop.

But what are the players thinking as this process unfolds? Are they excited, anxiety-ridden? I spoke with both former free agents and soon-to-be free agents in an effort to gauge what the process is like for them. Bear in mind, that for every Samuel or Briggs, there are two or three players who wish their contracts had never expired.

Players who fall into this category are about to hit the lottery. Within hours, if not minutes, after midnight, Samuel and Briggs are likely to receive offers of guaranteed money well in excess of $20 million. The total contract value will likely exceed $50 million each.

Another top-tier player likely to experience a financial boon is Jake Scott, an offensive guard/tackle who played the four previous seasons with Indianapolis and has been a starter since midway through his rookie season in 2004. With players like Steve Hutchinson, Eric Steinbach and Derrick Dockery recently re-setting the bar for top offensive guards, Scott will join Alan Faneca as one of the top guards available on the free agent market.

"I am really more excited than nervous," said Scott, "I know I am going to get something done quickly and gonna go somewhere."

It's not uncommon for a top-tier free agent to be on a plane the first day of free agency and likely sign a contract three or four days later, if not sooner -- one that could provide financial security for the rest of their life.

Though Scott would love the opportunity to return to the Colts, the team that drafted him and the team he helped win a Super Bowl, his increased value has probably priced Indy out of the market.

"I have not really heard from them in a while and don't expect to," he said. "I had four good years there, but they are pretty tight against the cap and I know there are other teams that are interested in me.

Most first-tier free agents gravitate to the highest, and Scott is no different. After all, this is a business. But there are other factors that he says he'll take into account.

"I want to win. Football is not fun at all when you aren't winning," he said.

So what numeric value would he place on the importance of winning? Scott said he could envision a scenario in which he took 10-15% less to sign with a team that had Super Bowl potential.

That is borderline philanthropic in a league in which, as one assistant coach said, free agent decisions "always come down to money."

Who could blame Scott for maximizing his full financial potential? He has made the playoffs ever year, won a Super Bowl in 2007, and protected arguably the best player in the game for the past four years. But he didn't break the $1 million mark for career earnings until halfway through last season. The guaranteed money in his next contract will likely surpass his career earnings up to this point by a minimum of tenfold.

Not every free agent has the good fortune of being in the upper echelon of available players. Tight end Mark Campbell and defensive end Ryan Denney, for instance, had slightly different experiences when they hit the market in 2006.

Campbell was initially happy when he was released by Buffalo in a cap-saving move before free agency began. As the days mounted, his thoughts began to waver.

"I think it is a case of be careful what you wish for sometimes," he said. "I was happy to be a free agent, but when nobody called the first couple of days, I began to worry. We had just had our son in November and I felt a strong sense of duty to provide for my family. I really had a tough time sleeping. I'd get up at 5 a.m. and work out for two or three hours to burn the nervous energy. I didn't really hear from anyone until eight or nine days after free agency started."

While Campbell spoke with his agent on a daily basis during the process, Denney said he spent a great deal of time on the Internet, looking to see what other defensive ends were getting paid.

"It is tough to watch other players at your position -- players who you think you are as good as -- getting contracts that are significantly higher than what you are being offered," said Denney.

Ultimately, Denney and Campbell had to wait until first-tier players signed their big-money contracts before they could see what options were left on the table. Denney made a visit to Kansas City but chose to re-sign with Buffalo. Campbell landed in New Orleans.

This tier consists typically of veteran back-ups who have not received a lot of playing time in recent years and special-teamers who don't know if another team will value their skills in the kicking game.

I was a third tier free agent a year ago and it was a very unpleasant position to be in. While other players are enjoying the fruits of their labor, I was just hoping to have the opportunity to keep the dream of playing in the NFL alive another year. In addition to the work of my agent, I called several coaches whom I had played for earlier in my career. Gregg Williams, then of the Redskins, and Hue Jackson, then of the Atlanta Falcons, both expressed an interest in bringing me in to improve the depth of their team's offensive line. I was fortunate to sign a contract within Washington and receive another opportunity in the NFL. Many others are not so lucky.

There was plenty of feedback after my column last week on HGH and steroid use before the combine and pro day events. One active player mentioned that "it would just be too hard to take steroids because of how often we get tested. You would really need to be under a doctor's supervision." Another player, however, felt there would always be a "certain level of doubt" about HGH until a test is implemented. Here are a couple of questions that readers wanted answered.

• How can players allow the combine/pro day pressure lead them down the path of using performance-enhancing drugs?

Very easily. Imagine working seemingly your entire life towards one goal and then finally staring that opportunity directly in the face. Now imagine that a small difference in your weight, 40 time or vertical jump could be the difference between getting an opportunity or not, of getting drafted or not, of making millions or not. I don't condone players going the performance-enhancing drug route, but I recognize the dynamics that leads some to do so.

Like several of the players I spoke with before writing the column and afterwards, I briefly considered taking steroids to help ensure that I could play in the NFL. I was a well-educated Princeton senior in 2000 and had already accepted a job on Wall Street, yet the allure of pro football was great. I just wanted a chance.

The fact that I played my senior season with a sports hernia (which wasn't repaired until December 2000) and that I wasn't invited to the combine only fueled my sense of urgency. A lot of scouts will not even put in the film work necessary to evaluate a small school prospect until he has proven he has the numbers that legitimize him as a potential prospect. That's the position that I felt I was in.

Ultimately, I decided against using steroids for a number of reasons. Chief among them was my desire to see what I could accomplish without the aid of any performance enhancers. If I wasn't good enough to get into the league on my own merit, then so be it. Aside from that, I would not have known where to get steroids from, how to take them, how I would afford them, and what the potential negative health repercussions might have been. Clearly, these factors are not enough to dissuade every player from a shot at their dream.

• How big of a problem is HGH use among NFL players?

I wish I knew. Most of the players with whom I have spoken tend to agree with my assessment that it is not a widespread problem. But given that a former teammate of mine, Rodney Harrison, was suspended for four games for purchasing HGH, it certainly makes me wonder who else might be doing the same thing.

That wonderment is really the crux of the problem. As I get closer to filling out my retirement paperwork in June, I can't help but wonder how many of my peers or opponents used performance-enhancing drugs.

Did I get beat out for a starting position with the Redskins because my competition had taken steroids or HGH? Or was he just naturally better? If I had secured the starting job, how different would my career have been?

Were my opponents able to bull-rush me effectively because of my shortcomings or possible steroid use on their part?

I have often said that I wish someday I could get a list, 20 years from now, that told me exactly who did and who did not take performance-enhancing drugs during their NFL career. I would just like to know where I really stood among the game's elite.

That list, however, will never be compiled, and so my thirst for the truth will never be quenched. In the end, isn't that why we need to find a way to rid the game of any doubt about the legitimacy of its players' accomplishments?