NFL players concerned about past, future as they work to end lockout

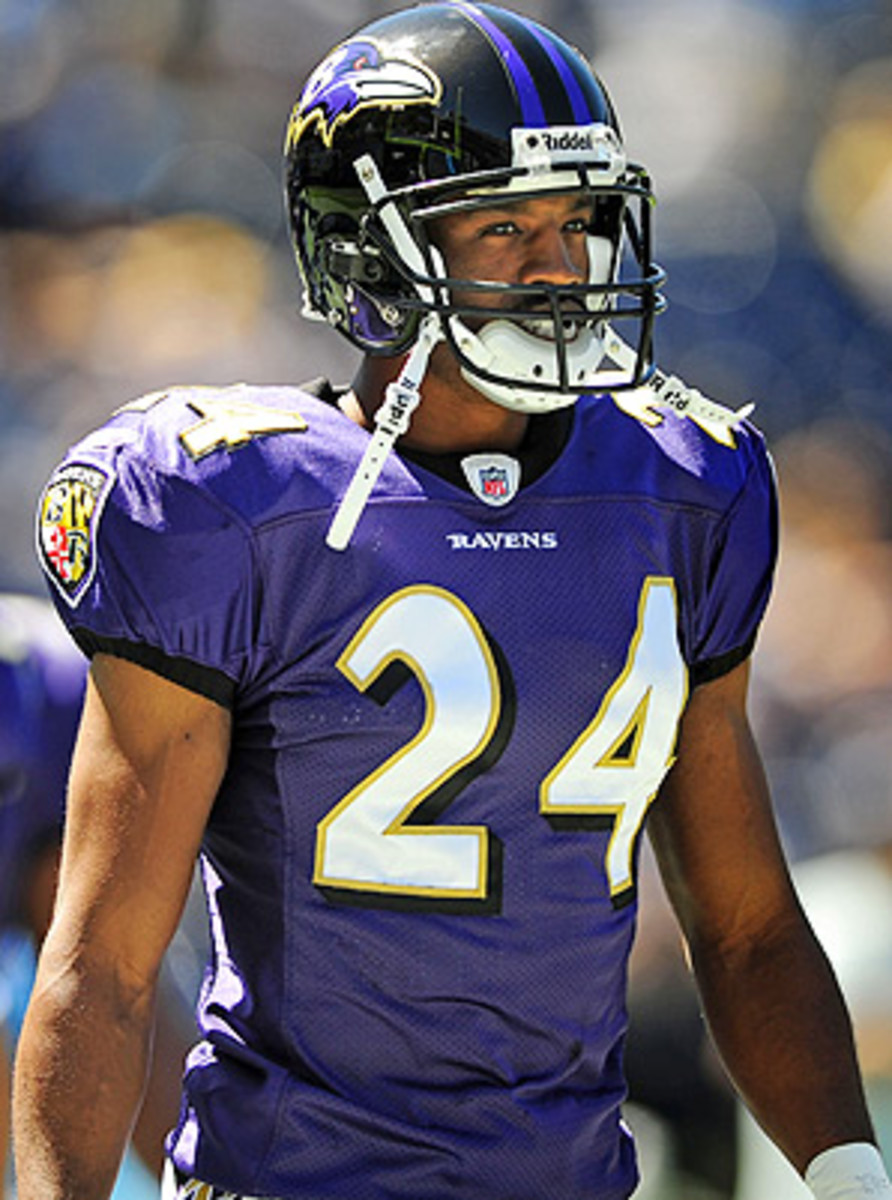

With Peter King on his summer vacation, Ravens cornerback Domonique Foxworth took time away from the offseason to write today's Monday Morning Quarterback column. Foxworth is entering his seventh season in the NFL and third in Baltimore, after spending time in Denver and Atlanta. Foxworth is also a member of the NFLPA executive committee and has been in the room as the NFL and the players try to work out a resolution to the ongoing labor standoff.

"When is this lockout going to end?"

It's a question I hear in one variation or another nearly every day whenever I am approached by NFL fans of all allegiances. Just this weekend, for instance, while I was at the store picking up some diapers for my daughter, a woman approached me with this now-familiar refrain: "When are you guys going to get back on the field?" As I began to try to answer her question, she blurted out, "You don't understand. Without football, we won't make it!"

I know, perhaps even better than she realizes, where she is coming from. In 2009, when I signed with the Baltimore Ravens as a free agent, I was euphoric. Not only was I living out the childhood fantasy of playing for my hometown team -- I grew up in the Baltimore area, and played college football at Maryland -- but also I was joining a legendary defense on a team ready to compete for a Super Bowl championship. Unfortunately, we fell short in our quest in the AFC championship game, but I went into the offseason with the highest aspirations for the team's performance and my own that next season.

In those days between when the Lombardi trophy is handed out in February and the preseason begins again in August, I was hard at work training, studying film and talking strategy with my teammates. With the most anticipation I carried into any season of football in my life, I finally stepped onto the practice field on the first day of training camp ready to help the Ravens win an NFL championship. The anterior cruciate ligament in my right knee, however, had different plans. I tore it during non-contact drills, and the result was my first fall without football since I was 8.

A torn ACL is a season-ending injury -- one of the ones that makes you press the reset button on in Madden's Franchise mode rather than deal with the consequences. In real life, of course, there is no such thing and thus I spent the entirety of last year on the sidelines, nursing the pains of a torn ligament and the deep frustration of losing something so personally important.

Now, with the labor agreement between the NFL Players' Association (NFLPA) and the league expired, we are all -- players, owners, stadium and team employees, small business owners, and most importantly, fans -- facing the possibility of missing out on a season of football if we do not come to an expedient and fair resolution. I have no desire whatsoever to miss any of the 2011 season, and, given the arduous road back from last year's injury, I would contend that my enthusiasm to get the league back to work exceeds anyone's. Indeed, I have worked on the NFLPA's executive committee in labor discussions for the past two years precisely to ensure that this will happen -- but it must happen fairly.

***

There is adage that says, "Wise men don't argue with fools, because people from a distance can't tell the difference." Unfortunately, it often appears from afar that the NFL labor discussions are nothing more than an argument between fools, or a greed-driven errand more akin to a game of Hungry, Hungry Hippos, whose only end is who has the most marbles. Speaking from the perspective of the players, however, we are fighting for things you're more likely to find in a game of LIFE: a safer practice regimen, better pensions for former players, long-term health insurance and more time and support in the pursuit of higher education and post-football careers.

The fight over these benefits is a cause the players, like union workers in many industries, are willing to stand in solidarity for. We are not only taking this stand for ourselves, but also for former players from a less lucrative era, and future players who will take the game to new heights.

We are also living up to the responsibility that the NFL has as the professional league and guiding force for our sport in this country and around the world. What our league does is emulated by all who play our game, from 6-year-olds playing Pop Warner football, to high school athletes carrying their towns' hopes, to young men trying to make a name for themselves on the college gridirons.

Leading scientists have gathered increasingly conclusive data on the dangers football players face from collisions in practice and in games. A University of Michigan survey of former NFL players has found a rate of memory-related diseases (i.e., Alzheimer's, dementia) that is five times higher than the national average for those over 50, and 19 times higher than the national average for those between 30 and 49.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill researchers recently published a series of studies that show that NFL players with three or more concussions were more likely to be clinically depressed, three times more likely to experience significant memory problems, and five times more likely to develop early-onset Alzheimer's.

We cannot compromise on player safety, especially in reference to the number of hits to the head during the preseason and in practice, which neuroscientists have come to consider as important long-term as in-game collisions. We are not only aiming to protect today's gridiron stars from futures of depression and dementia, but also to lead the way in protecting our young people in college, high school, and youth leagues. This can be the sterling legacy of our generation to the future of football.

Meanwhile, the entire NFL has a duty to the "gladiators" who paved the way for the league's current success by sacrificing -- often without knowing to what extent -- their minds and bodies to live up to the game's traditions. We will proudly stand for improving the pensions for former players and the message it sends.

Players who retire from the NFL leave with, at most, five years of health insurance, but often with several lifetimes worth of injuries and recurring mental health issues. Elvin Bethea, the Hall of Fame defensive end for the former Houston Oilers, for example, has had over 25 operations relating to his football career and racked up astronomical medical bills, all without the pension support that other professional leagues provide to their retired athletes.

Finding a way to guarantee that the players giving everything they have out on the field receive adequate health insurance is not a nicety, it is a necessity. Improvements on this front will not only give our players, their wives, and children an important sense of security, but also ensure that players who suffer serious injuries will not fall on hard times.

***

A fair settlement to this lockout provides this sort of support for players and has consequences well beyond the field. Having healthy and productive ex-NFL players can be a great benefit to our cities and communities. Ex-players like Bert Emanuel, Jack Brewer and Jamal Lewis have all started successful companies, with a number of employees, in field such as financial services, sportswear and trucking. The NFLPA is committed to developing the full talents of our players both on and off the field, by providing for a more genuine "off"-season and more extensive league support for players pursuing educational, business and public service opportunities.

The existing offseason is a relic of a bygone era where athletes were less likely to stay in football-shape. During the lockout, far from getting heavier, my teammate Haloti Ngata has lost 25 pounds and become even quicker than before.

Several NFL players have used the time off during the lockout to concentrate on these dimensions of their lives, and have become more well-rounded people and role models because of it. Troy Polamalu of the Pittsburgh Steelers, for example, completed his bachelor's degree in history from the University of Southern California. In a statement on his website, Polamalu said it "was very important to me personally, because I want to emphasize the importance of education, and that nothing should supercede it."

A number of athletes, despite our profession's less than stellar academic reputation, share this sentiment, and take part in existing programs like the institutes the NFL has run at Harvard Business School and the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Business.

This initiative and dedication to education prepares players for a more impactful life after football. It readies them for a much better opportunity to create successful businesses that employ our neighbors or become public servants that advocate for important issues. With greater support our athletes can even better promote the importance of education and giving back.

When I returned home to Baltimore, I started a non-profit program for boys called Baltimore BORN, which provides supplementary educational programming, individualized mentoring and tutoring support, and other growth experiences, including summer camp scholarships and year-round enrichment activities to low-income boys. A more efficient offseason would allow NFL players -- many of whom are working on community service projects with great potential -- to devote more time to these important off-field pursuits.

***

So what happens next and when will we see an end to this lockout? The short answer is: I don't know. I have been in the room during all of the most recent discussions and the news I can share is that players are focused and working hard to offer solutions to the issues we have identified. I will not speak on behalf of the owners, nor will I breach the confidentiality of the talks, but I feel strongly that we must push even harder to find a resolution as we are approaching a critical time.

I don't think about, nor do I want to characterize the mood as "optimistic" or suggest that "we're close." All of that is relative. The fans want to see football and I want to play it. Right now, neither one can happen. Players know what's fair and we know what's right. As an NFL player on the field, I have a job. If I don't get that job done consistently, I lose my job. I don't ever hear a reporter saying that my coverage of a certain wide receiver was "close." That's how I feel about this lockout. It's still a lockout.

The more pertinent question in my mind today is: Where do we begin? This week, the NFL Players Association will host "The Business of Football: Rookie Edition." Nearly 200 drafted players will get together to discuss all aspects of how to be a successful professional football player. The issues covered will include financial responsibility, and a group of experts will share some knowledge with the rookies.

Where do we begin explaining to them what kind of business they are entering? Where do we begin talking about what their impact is on the community? Where do we begin to share with them the risks associated with being an NFL player? Players, now more than ever, are entrusted with shaping the future of the game. I think we have a tremendous responsibility to players past, present and future to get it done. We can't fail them and we won't.

1. I think the Falcons are going to be a tough team in the NFC. Watching Matt Ryan, with one more year under his belt, and rookie wide receiver Julio Jones opposite Roddy White, plus a healthy Micheal Turner, could be exciting.

2. I think the intensity in the Ravens-Steelers rivalry is the best in the league because of the similarities of the two cities. The tough, no excuses, blue-collar culture of each city is embodied by both teams and is never more apparent than when Baltimore and Pittsburgh compete on the field.

3. I think Baltimore should get to host a Super Bowl. If Detroit can handle the country's biggest game, then so can Charm City.

4. I think the NBA players are in for a tough fight in their labor situation and should remain strong. It is going to be a tumultuous several months. There will be a number of obstacles, pressures internal and external, expected and unforeseen. Good luck.

5. I think these are my non-sports thoughts:

a. Today's technology is amazing. At least once a month I look at my smartphone or iPad and say, "Holy $*&@, this is incredible."

b. Hey, fellas, you should be clothed in your Twitter profile pic. Nothing is more unsettling than reading "The US economy is in shambles. We can't afford to raise the debt ceiling" while looking at greased-up abs.

c. I think the education crisis is today's civil rights movement. Our inability to provide high level education and opportunities to children in every community is just as oppressive to some children as an America that permits racial discrimination.

d. I think cell phones have ruined pushing people into pools.

e. Whenever someone says, "I'm not book smart, but I'm street smart," all I hear is, "I'm not real smart, but I'm imaginary smart."

6. I think I'd like to thank Peter King for the opportunity.