This Was The XFL: Pro sports’ most disastrous experiment gets a second look

Imagine a nightmare born of testosterone and cynicism that 16 years later remains an endeavor nearly too foolish and disastrous to be believed. Or re-live it! This Was The XFL, which debuts on ESPN Feb. 2 at 9 p.m., marks the latest sharp entry in the 30 for 30 documentary series, and it’s an instructive one, too. To this day, the XFL remains a black mark on Big Media and on American men, a feat of comprehensive stupidity, a triumph of the worst instincts. (To director Charlie Ebersol’s credit, he accurately paints the failure authored by his legendary NBC Sports exec father, Dick, and WWE’s Vince McMahon as borderline-contemptible rather than a well-intentioned moonshot along the lines of the USFL.)

Marketing was all the league had to offer. “X.F.L.” from the get-go stood literally for nothing; ”Xtreme Football League,” which was popularly thought to be the referent, belonged to someone else. This was just one way the league was out of its depth.

Atlanta Rising: The Falcons and their fan base embark on a new era

Pertinently, when he launched the XFL at a glitzy press conference in midtown Manhattan on Feb. 3, 2000, McMahon had no franchises, no coaches, no players, no television deal, no stadiums. He brought no football experience or novel ideas for the game… therewas no league. He was just a carnival barker in an ill-fitting suit, selling a fantasy.

Except… he had a gambit. He told the crowd and the cameras that the football establishment had lost its way. “Where’s the kind of football that the NFL used to be? Where’s my smash-mouth, wide-open football? It’s gone… We will take you places the NFL is afraid to take you, because we’re not afraid of anything.”

About that: Then, as now, the NFL was a witless behemoth, an institution that did right by all the wrong stakeholders and wrong by all the right ones. It moved too slowly except when it saw an opportunity to pander. It deserved and deserves much of the criticism it got and gets. Yet this particular attack was opportunistic and fatuous—the NFL wasn’t tough enough? The changes time had brought to the league were mostly good ones, supporting rather than stifling its best athletes. So Vince McMahon of all people was going to restore the glory of pro football?

Could such a nonsensical, vapid idea go anywhere? Well, no, not without the help of a desperate media. But with Ebersol in search of any football-like programming to boost his ratings after CBS won the AFC television contract in 1998, NBC bought in. The World Wrestling Federation and NBC became 50–50 partners in the league, intertwining the fortunes of this crass ringmaster and this ratings-dependent business, and in the process conferring legitimacy onto the league. NBC had had Toscanini, and now it had ER; NBC was familiar and iconic—how bad could the XFL really be? The network produced promotional spots that showed a putative apocalyptic training camp, with a Mack truck in place of a blocking sled, and a wrecking ball on punt coverage. Sponsors signed up in droves before the February 2001 premiere.

How huge the audience was on that first night! That first telecast doubled its promise to advertisers, bringing in a 9.5 rating, about 10 million viewers. What a spectacle: McMahon had taken the field pregame to bellow “THIS IS THE XFL” in his best wrestler voice, and Dick Butkus had accompanied him; Jesse Ventura was alongside Matt Vasgersian in the booth; the game’s director paid ample attention to the revealing outfits of the Las Vegas Outlaws cheerleaders while also using the Skycam for the first time in professional football. It was immaculate television.

Blanket Coverage: Recent coaching hires stray from the NFL's winning formula

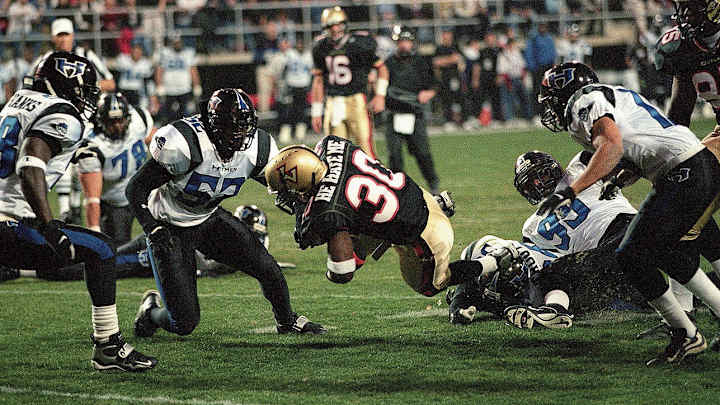

The football, though, was a disaster. These were not, by and large, the best people; NFL washouts and never-weres filled the rosters and coaching ranks. Because of poor planning, players were given only a month in training camp to cohere into full-fledged teams. Ebersol says in the movie, “I thought we were going to deliver good football. I don’t believe in my entire career in sports or show business, I was ever more wrong.” But of course the football was going to be bad—the league was nothing more than a contrarian sales pitch. Those dangerous, ballyhooed ideas that were supposed to shake football to its core? They were worse than what the NFL offered. Its no-fair-catch rule confused players; its game-opening possession scramble caused injuries to some of the league’s best athletes; its lax approach to bump-and-run coverage depressed scoring. The score on opening night was 19–0; NBC cut to another XFL game midway through.

Reasonable people tuned out from the XFL immediately thereafter, as the novelty wore off. Americans were curious, and then they weren’t. Perhaps they were horrified. They didn’t show up the next week—when, showcasing the incompetence of all involved, the telecast went dark because of an empty gas tank in an NBC generator, then ran so long Saturday Night Live started after midnight. More supporters defected as the season went on. McMahon would demote Vasgersian, a moderating influence, for failing to comment enough on the cheerleaders’ bodies, and replace him with old wrestling hand Jim “J.R.” Ross. Ventura was sent from the booth to the sideline to pick fights with players and coaches. The Los Angeles team put a hot tub behind one end zone and called a local strip club to fill it. Late in the season, the games were posting numbers that were among the lowest in the history of network primetime. (Only three percent of turned-on televisions were tuned to the game.) NBC, whose initial support had built the league, backed away from what it had wrought. And as McMahon lost support, he lashed out against the media.

NFL in action: How President Obama inspired a new wave of athlete activism

“Unfortunately, the media just can’t wait for this to die. I would hope the media dies before the XFL does,” he said. In one spirited interview with Bob Costas—agreed to in hopes of resetting the league’s relationship with the sports media—McMahon lost his cool, pointing his finger, screaming at Costas, with veins bulging, “Do you realize how many people enjoy, on a global basis, World Wrestling Federation entertainment that aren’t elitists like you?”

Mercifully, the league folded two months after that interview and one month after its championship game. Onetime NBC Sports president Ken Schanzer says in the film, “It all goes back to the success of our promotion and the failure of our execution. You just can’t do that.” The XFL ought to be remembered for three traits above all: its cunning approach to television, its eagerness to degrade women and its total failure to achieve anything like what it promised (owing to the shallowness of its ideas). Three months after it launched, everyone involved was tarnished and poorer.

Presumably a lesson was learned, and nothing like the XFL will ever happen again. Well, at least not in pro sports.