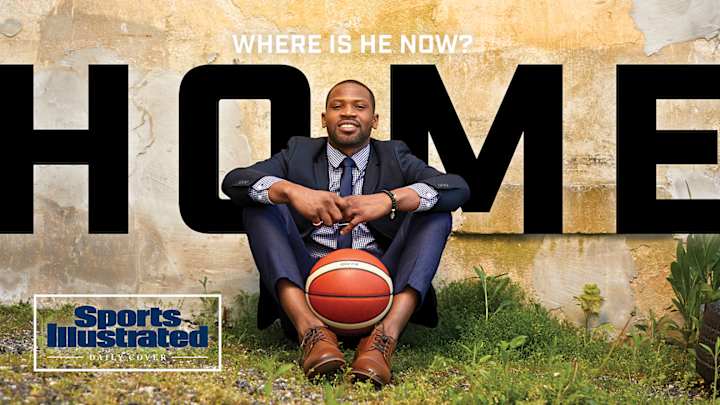

When COVID-19 Hit, Isaiah Lamb Headed Home—Because Now He Has a Home To Go To

He was 6,000 miles from his family and friends in Baltimore, and incalculably further culturally. He didn’t speak the language. He was cold, even when the wind didn’t whip. His girlfriend was in Iceland, multiple time zones and flights away.

But Isaiah Lamb didn’t want to leave Armenia. In the several months since he’d arrived in the unlikeliest place to play pro basketball, he’d grown to like the country and revel in its charms, in his own fish-out-of-water story. This wasn’t the NBA, but he was thrilled to be playing in a league where coaches didn’t adhere to a rigid system, where they let their players ball. At 6' 4", Lamb could get his shot off against any defender in the league. He wasn’t making millions, but he was making out O.K. His team, Aragats, in the Armenia Basketball League A, provided him with an apartment; food was cheap; and his paycheck more than covered his expenses. He was traveling to places he’d never dreamed he would set foot—Russia, Belarus, Georgia. “All and all,” he says, “yeah, I was happy. More happy than homesick, that’s for sure.”

But then came the coronavirus. Even in Armenia’s capital, Yerevan, not far from the Turkish border, the virus did its equivalent of a Eurostep. And so in March, Lamb, grudgingly, made plans to head back to the U.S. It was a long flight, almost 24 hours, and after that inconvenience he would suddenly be unemployed. Working from home, taking Zoom calls all day, is, of course, not an option for a professional basketball player.

Isaiah Lamb, though, is to optimism what Steph Curry is to outside shooting. We’re talking world-class-practitioner level. And it didn’t take much to soften the blow of his first professional season ending prematurely. See, there was this: When he told teammates he was “heading home,” he was referring to a physical location. Which had not always been the case.

***

One of the cardinal journalistic crimes, a seminal act of storytelling malpractice, entails burying the lead. Don’t wait too long to share a critical detail with your audience. So let’s state this upfront: Here comes a happy story, a source of light in this time of darkness. And, speaking personally, here comes a Where Are They Now? update I’ve never had more pleasure in delivering.

I first met Isaiah Lamb in the summer of 2014. Kevin Durant, you’ll recall, had just won the NBA’s MVP award and delivered a memorable speech. He turned to his mother, Wanda Pratt, and, voice quavering, said: “Everyone told us we weren’t supposed to be here. You made us believe. You kept us off the street, put clothes on our back, food on the table. When you didn’t eat, you made sure we ate. You went to sleep hungry, you sacrificed for us. You’re the real MVP.”

It was an almost unendurably touching moment. Durant and his mom deserve all sorts of credit for persevering through a period of bleakness. But their experience presented questions. How many other U.S. athletes are homeless? And, heartening as it is to hear successful athletes reflecting on overcoming hard times, what is it like for athletes in the present tense to play sports without a "fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence,” such is the Department of Education’s definition of homelessness?

Teaming with investigative journalist Ken Rodriguez, Sports Illustrated started probing the issue, and it quickly became clear that there are no federal statistics on homeless athletes. But extrapolating the data and talking to experts led us to conclude that between 80,000 and 100,000 high school and college students play sports—sometimes at the most elite levels—while lacking permanent shelter.

To personalize this issue, we began looking for subjects. Soon a high school coach in Maryland contacted us: “I have the sweetest kid you could ever imagine, who’s gone through some unbelievably rough times.” As scouting reports go, this was dead on.

At the time, Isaiah Lamb was a rising senior at Dulaney High, outside Baltimore. A small forward, he could dunk with ease, penetrate with a subliminally quick first step, and also, reliably, stick outside shots. This success was all the more remarkable given that he’d spent much of his teen years pinballing around Maryland, sometimes sleeping in his family’s 2002 Hyundai Elantra, parked outside a laundromat called Sudsville, where he would do his homework on a folding table and brush his teeth in the bathroom.

There had been no single trauma that befell the Lamb family. Isaiah’s adoring parents were hardworking folks who, too often, had a lousy relationship with luck. His mother, Valerie, a dignified woman with a voice so high it sounds like she sings when she speaks, had worked a series of jobs. His father, known to all as “Lamb,” suffered a heart attack and was laid off from his job at a nursing home.

Read Isaiah Lamb's Sports Illustrated cover story from 2014

Suddenly, the family’s expenses edged out its income. The smallest emergency—car trouble, an unexpected bill here, a doctor’s visit there—compounded matters. And soon Isaiah was among the million-plus homeless children in the U.S. “Sleeping in a car when you’re 6' 4" is absolutely terrible,” he said. “I would just lay in the backseat with bags. … To be in a parking lot—hoping that no one you know walks by and sees you—is pretty rough.”

As it turned out, shortly before my visit the Lambs found a ground-floor apartment they could afford, not far from Isaiah’s school. The family, however, had nothing left over to spend on furniture, leaving Isaiah to sleep on an air mattress. Before our interview, we purchased stools from Target so we could speak sitting down while recording a video.

In October 2014 the story came out, and Isaiah was on the cover of Sports Illustrated. “It changed my life,” he says. He was a high school senior and, overnight, there were invitations to go on television, requests to autograph the cover as if he were LeBron or KD. He was relieved that teammates and classmates finally knew why he never invited friends over for sleepovers or parties. There was a slight backlash over his wearing expensive Air Jordans for the cover shoot, trolls questioning how he could be homeless and have such sweet kicks. His response? “I borrowed those from a friend. I didn’t want to wear my ratty shoes on the cover of a magazine!”

A few weeks later, Lamb tore his right ACL. He’d endured homelessness and hunger, but this was, he says, “one of the few times I really got depressed.” Most of the 20-plus D-I programs that had been recruiting him—dangling not just scholarship offers but promises of a better life—retreated. One school that kept its word: Marist College, a Catholic school in leafy Poughkeepsie, N.Y., best known in basketball circles as the alma mater of Rik Smits. When Lamb arrived as a freshman, he worked through the last bits of rehab. By the time basketball season arrived, he was doing this.

College ball was something of a mixed bag. Lamb took a while in regaining the explosiveness that his ACL injury had blown up. In a new system, he was seldom his team’s first option on offense. After the Red Foxes went 21-72 in Lamb’s first three seasons, there was a coaching change. Then again, Lamb started the majority of the time. He got to play against Grayson Allen’s Duke (“I was looking forward to Jayson Tatum, but he was injured!”) and Jevon Carter’s West Virginia. By Lamb’s senior year, he was named a captain.

Time and again, people would approach him before games and ask him to sign his Sports Illustrated cover. Occasionally, he’d get calls from the media, asking him to update his story. He generally complied, but, he says, “I wanted to talk about basketball. I didn’t want to keep repeating the same story. But, yeah, a lot of people recognized me.”

Leave it to Lamb to see this all as a disguised blessing. Perceived as a classmate and not a future star, he enjoyed a “generally wonderful” college experience. He took classes in new subjects. There were late-night dorm room conversations about matters large and small. There were trips abroad, marking the first time he left the country. His freshman year, he started dating a player on the Marist women’s team, Lovisa Henningsdottir, a native of Iceland. On the surface, anyway, their backgrounds could scarcely be more different. They are still together.

Meanwhile, outside of Baltimore, Lamb’s parents moved again and endured another brief period of homelessness. Finances were always tenuous. But Isaiah took some solace in knowing that, at a school where tuition, room and board can run $60,000 a year, he was on scholarship.

If you are—not wrongly—cynical about the “student-athlete” who arrives on campus as an unpaid vassal of the athletic department . . . well, consider Lamb some strong counterprogramming. He graduated in 2019, majoring in marketing and minoring in communications. In school he was inspired to launch Lo-Lamb, an online fitness business, starting by selling core sliders. “Growing up, I didn’t have access to a gym,” he says, “so I would always do push-ups, sit-ups in the house; use what I have. If I had a heavy water jug, a book bag, I’d lift that. Use your own bodyweight as your resistance.” He learned about ecommerce and expanded the business to apparel, including sneakers and beanies, fanny packs and, now, protective face coverings.

If his basketball dreams had eroded, they hadn’t died. After graduation, Lamb entertained offers to play overseas and settled on Armenia. By this point in his life he’d already done the culture-shock drill; he was spared the sense of displacement that besets so many other players who venture overseas. He was happy to cook his own meals. He took online courses to get his personal training certificate. (He started offering fitness classes on Instagram Live.) And as a swingman he put up his biggest numbers since high school, averaging more than 20 points per game and playing himself into contention for the league’s equivalent of the MVP award. Valerie and Lamb kept absurd hours streaming their son's games on YouTube.

Now back in Maryland, for the time being, he lives with his parents in a new apartment in Parkville, near the campus of Morgan State University. His mom works as a tech in the emergency department of a nearby hospital and is as busy as ever. Both his parents, he reports, are healthy. If or when the current epidemic subsides and life returns to some semblance of normal, Isaiah hopes he can continue playing overseas, but this time in Iceland, where Lovisa relocated after school to play ball.

Still only 23, Lamb is already philosophical about his story. He’s as eager as anyone for another Where Are They Now? dispatch, a few years down the line. He concedes: His experience is not quite the Kevin Durant Cinderella story, but, “hopefully people can see me and see that it doesn’t always turn out how you want it. [That’s] normal. There’s such a slim chance of going to the NBA.”

“I’m really happy with where I’m at,” he says, but “I have tons more to do before I’m satisfied.”

Jon Wertheim is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated and has been part of the full-time SI writing staff since 1997, largely focusing on the tennis beat , sports business and social issues, and enterprise journalism. In addition to his work at SI, he is a correspondent for "60 Minutes" and a commentator for The Tennis Channel. He has authored 11 books and has been honored with two Emmys, numerous writing and investigative journalism awards, and the Eugene Scott Award from the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Wertheim is a longtime member of the New York Bar Association (retired), the International Tennis Writers Association and the Writers Guild of America. He has a bachelor's in history from Yale University and received a law degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He resides in New York City with his wife, who is a divorce mediator and adjunct law professor. They have two children.

Follow jon_wertheim