In Push to Restore HBCU Wrestling, Athletes Regain Their 'Choice' Starting at Morgan State

Jahi Jones was moments away from standing eye-to-eye with his opponent on the mat for the 2020 NCAA Division I wrestling championships. After qualifying for competition on the biggest stage—despite setbacks and a pursuit of persistence—his dream of competing in front of thousands at U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis was finally happening.

Or at least, so he thought.

The emergence of the coronavirus in the U.S. canceled all remaining winter and spring NCAA championships that March. He was devastated.

“I was having the best season I’d ever had when COVID-19 ended my chance to compete for a national title,” Jones says.

So Jones did what he’s always done, even back before his collegiate wrestling dreams ever became a reality: He persisted. And he found a new way to live out his passions in the sport.

“I had no plans to attend college if I could not wrestle,” says Jones, who is currently finishing up the final semester of his master’s degree in business analytics at Maryland.

When he graduated from Oxon Hill (Md.) High School in May 2015, Jones, a Prince George’s County native, applied to only two universities in Maryland: Morgan State, a historically Black college and university in Baltimore, and the University of Maryland in College Park.

Jones, then a 145-pound wrestler, opted to become a Terrapin that fall because Morgan State lacked a wrestling program. The Bears’ program had been on hiatus for 24 years due to a lack of funding and resources.

There was still one big problem: Maryland offered Jones only an academic scholarship and not a spot on the wrestling team. But his persistence would not let him take no for an answer.

“I tried to walk on the [Maryland] team my freshman year, but I got cut [in favor of] a guy who ended up being one of my best friends to this day,” Jones says. “We laugh about it all the time now.”

Two years later, Jones made another attempt at his collegiate dream. This time, he struck gold. He joined a Terrapins wrestling team rich in success, with 24 conference championships in school history, tons of all-time letter winners and two individual NCAA champions in 1965 and ’69.

A year later, during the 2018–19 season, he was voted the team’s captain by his teammates and was awarded the Big Ten Medal of Honor, the first person in Maryland wrestling history to receive the prestigious award.

Jones finished his bachelor’s degree in May 2019 but decided to return that fall to use his last year of wrestling eligibility and to pursue a second degree. It was the perfect way to prepare him for the next phase of life—mastering business with his love for wrestling. However, the way Jones envisioned intertwining the two took a twist.

While COVID-19 ended his dreams on the mat, his experiences prepared him to be a champion for people. After shifting his focus, Jones began a new mission: advocating for access to greater opportunities for young athletes, with wrestling at the forefront.

Jones is the director for the Historically Black Colleges and Universities Wrestling Initiative (HBCUW), a first-of-its-kind program geared toward restoring wrestling programs at HBCUs and developing young Black wrestlers. In October, the program announced a $2.7 million donation to Morgan State, making it the only HBCU in the country that will have a D-I varsity men’s wrestling program starting with the 2023–24 season.

There are more than 100 HBCUs across the country, but many lack wrestling programs. However, take a journey back less than 50 years and HBCUs, including Morgan State, were hotbeds for the sport.

HBCUW board members and collaborators—that include Nate Parker, vice president of the Black Wrestling Association, two-time Olympian and two-time NCAA champion at Penn State Kerry McCoy, two-time Super Bowl champion Tony Dungy and well-known philanthropist and CEO of Galaxy Digital investment firm Mike Novogratz—strategically chose to invest in Morgan State.

Reasons included the university’s deep history in wrestling and the fact that students and wrestlers in the Baltimore community take advantage of the city’s Beat the Streets program, a nonprofit organization that helps students with their academics while helping them grow as wrestlers.

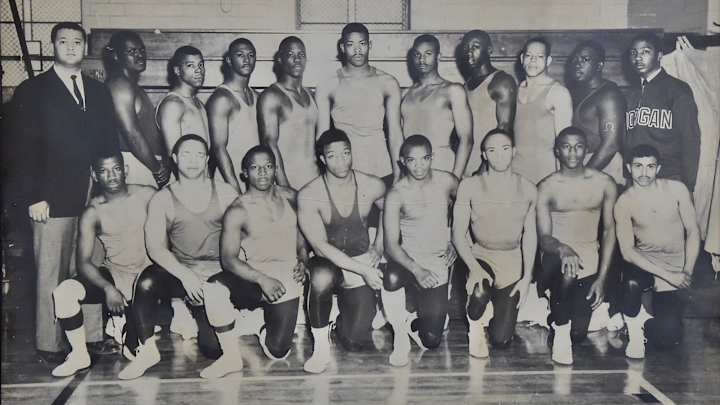

Morgan State hasn’t had a wrestling program since the 1996–97 season. Before the team was dismantled, it amassed great success dating all the way back to the 1950s. The Bears claimed three consecutive Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) championships from ’63 to ’65, produced 13 Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference championships, hosted the ’84 NCAA Eastern Wrestling Regional Championship and produced four NCAA Division II champions while hoisting four national champions and approximately 75 All-Americans.

Seeing this initiative come to fruition starting with Morgan State is truly humbling for Jones.

“Everybody’s not going to the NBA or the NFL,” he says. “Knowing that I created an opportunity for many Black kids who wanted to wrestle but did not have my persistence is better than any national title that I could ever have.”

Novogratz, a former wrestler at Princeton, believes that wrestling teaches leadership. He donated the first $6 million to HBCUW and told Jones that if the program could garner $1 million per year, he would match it going forward.

Initial HBCUW discussions to partner with Morgan State began in May 2020, says Jones. Novogratz, along with board members, began holding discussions about ways more Black leaders could be created.

In reestablishing a wrestling team at Morgan State, Novogratz hopes the program will serve as a leadership blueprint emerging from HBCUs.

“Fifteen of our 46 presidents wrestled as well as many important business, political and community leaders,” Novogratz says. “It’s about growing the sport of wrestling and our bench of future Black leaders who will make our nation more just and prosperous.”

Discussions around Morgan State came three months after the university hired Lydell Sargeant from UCLA to be an associate athletic director for development and revenue generation.

Sargeant, who has a huge interest in and understanding for wrestling, began a series of in-depth conversations about building a program with Edward Scott, vice president and director of athletics at Morgan State. With their vision, the two believe the program will change the lives of young athletes.

“If you’re a young athlete who aspires to go to an HBCU and pursue wrestling at the Division I level, you don’t have to make a choice anymore,” Scott says. “For so long, that choice has been taken away.”

Of the $2.7 million donation to the university, $1.5 million will be endowed and used to create up to nine scholarships while having 17 or more tuition-paying members, allowing the university to generate a stream of revenue. The remaining money from the donation will be used to supplement overhead expenses in launching the program over the next 10 years.

Brian Waters, a 2013 Morgan State alum and native Baltimorean attended Baltimore City College, a magnet high school in the city.

Waters says the program is a massive opportunity for wrestlers who don’t have the financial ability or opportunity to attend predominantly white institutions but still want to play on the collegiate level.

“These scholarships will put them in positions to change their lives,” Waters says. “Being able to wrestle while being surrounded by Black excellence is incredible.”

Beyond Morgan State, HBCUW will look to raise an initial $18 million over the next year to launch endowments for six HBCUs within the next five years and expand the Black community’s footprint and power within wrestling.

Five of the 10 champions from last year’s NCAA wrestling tournament were Black. Scott believes wrestlers from HBCUs can be in that conversation moving forward if the program is launched successfully.

“If we don’t do it right, all the eyes from the wrestling world are going to be on us,” Scott says.

Jones, too, echoed the sentiments of Scott’s philosophy, putting a broader emphasis on resources for future programs to create success.

“We want programs to be sustainable,” Jones says. “We want to ensure that coaches get competitive salaries. We want to put the best leader in front and build programs competing for championships.”

As the university focuses on the creation of its men’s wrestling team, the goal is to later bring a women’s wrestling team to Morgan State. Iowa recently became the first Power 5 school to add the D-I sport in September. Until then, HBCUW will aid in the preparation for the Bears’ program while continuing its search for schools to create wrestling opportunities.

Like Morgan State, other historically Black colleges and universities have struggled to keep their wrestling programs alive. In the last 45 years, HBCUs like Delaware State (2009), Norfolk State (1998), South Carolina State (’88), Howard (’02), North Carolina A&T (’77), Coppin State (’01), North Carolina Central (’80) and South Carolina State (’88) dropped their wrestling programs because of resources and lack of funding.

Now, with the vision of Jones and the initiative’s growing financial support, HBCUW has the chance to change the narrative around wrestling at HBCUs.

While Scott did not play the sport, he knows what success looks like in a wrestling program. Before coming to Morgan State, he spent seven years as an associate athletic director at Binghamton University in New York. Current North Carolina State wrestling coach Pat Popolizio was the wrestling coach at Binghamton during part of Scott’s tenure.

As Scott embarks on building a wrestling program from the ground up, he believes that providing opportunities for wrestlers of color will serve as a reminder that success on the mat is possible for athletes from any background.

“When you put two men on the mat, it doesn’t matter whether they are black or white,” Scott says. “You can’t hide your weaknesses. Wrestling teaches patience, teamwork, the power of endurance and competing with heart.”

Jones could have viewed the coronavirus pandemic as the straw that broke the camel’s back to his wrestling dream. Instead, he decided to keep pushing, just as he would on the mat against his opponent in competition.

“Life can come at you hard, and just like wrestling, you might get put on the mat,” Jones says. “But if there’s still time in the match, you’re still eligible to win and reach your goals.

“You can be any size or race; it’s a man-to-man battle. There is nothing like the humility and discipline this sport teaches you. So, when life comes at you like it did for me, the lessons learned from the mat come into play. Now, I am able to reach back and touch lives like never before.”

More College Sports Coverage: