AIAW vs. NCAA: When Women’s College Basketball Had to Choose

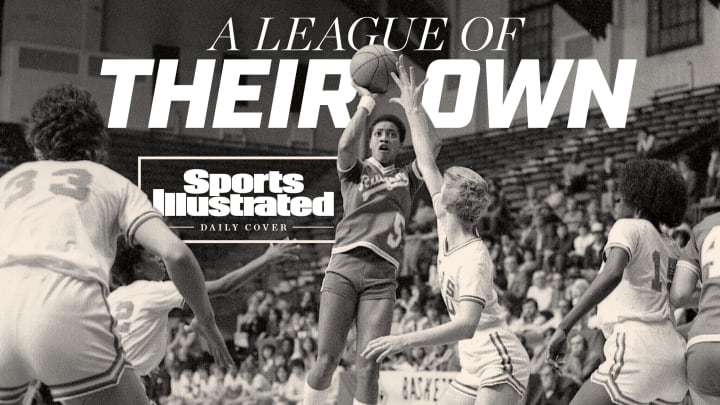

On March 28, 1982, No. 7 Rutgers beat No. 5 Texas to win the country’s most established women’s college basketball tournament.

On March 28, 1982, No. 1 Louisiana Tech beat No. 2 Cheyney State to win the country’s most competitive women’s college basketball tournament. It was a strange day, but those were strange times.

For the first time in its history—and nearly 10 years after the passage of Title IX—the NCAA was sponsoring women’s championships. Until the 1981–82 school year, that had been the province of the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, which both came into existence and held its first basketball tournament in ’72. With the two governing bodies each offering a trophy, schools could choose their tournament. That Tech and Cheyney went with the NCAA—which offered more perks, such as paying for transportation—was no surprise. Of the top 20 teams, 17 made the same choice.

How Rutgers wound up in the AIAW has been lost to time. “It was definitely above our pay grade,” says Mary Klinger, who, then known as Mary Coyle, ran point for the Lady Knights, playing alongside her twin sister, Patty. Even the team’s coach, Theresa Grentz, isn’t sure—the call came down from above and was never explained. “This was 1982,” she says. “The reasoning I got was, You’re lucky you’re even here.”

As for Texas, though, there was never any doubt that the school whose women’s sports were overseen by Donna Lopiano was going to ride it out with AIAW.

During the bubbled 2021 NCAA women’s tournament, players highlighted on social media the wide gap between their facilities and the men’s. Their posts sparked outrage—and pressured the NCAA into providing more equitable treatment this year. Similar pressure led to the women’s tournament finally being able to use the sobriquet of “March Madness” this season. To Lopiano, this was nothing new. By the time she sent her Longhorns to the AIAW tournament in 1982, she had seen enough of the NCAA to believe that it wouldn’t do right by women athletes—not unless it was made to.

She had grown up in pre–Title IX Stamford, Conn., playing sports with the boys on her street. “I don’t think I knew I was a girl until they told me I couldn’t play Little League baseball,” she says. Donna had been first pick in the draft but was prohibited from playing because the league’s bylaws banned girls.

So she played softball instead. Her dad, Tom, knew a scout for the Pirates who knew the coach of the Raybestos Brakettes, a local semi-pro fastpitch team. Tom had the scout come to dinner at his Italian restaurant, where ample amounts of food and—perhaps more significantly—Chianti were consumed. By meal’s end, Donna had a tryout.

In the sober light of day, the scout appeared to have second thoughts about vouching for a 16-year-old, so the car ride to the tryout was very quiet. When the drills started, he stayed in the car. But when he saw what Donna could do, he gradually moved closer and closer to the field, as if to say, Look what I brought you guys!

Lopiano spent the next 10 years traveling the world with the Brakettes as she completed her education, eventually earning a Ph.D. from USC. (She was inducted into the National Softball Hall of Fame in 1983.) She got a job in the athletic department at Brooklyn College in 1972, the same year the AIAW held its first hoops tournament.

The AIAW, composed almost entirely of women administrators, had been founded on a relatively simple ideal: Don’t make the same mistakes the men did. In an effort to avoid scandal, AIAW coaches weren’t allowed to recruit off-campus, and if a prospect visited a school she had to foot the bill. Scholarships were also forbidden until, ironically, the AIAW was sued for denying women the same opportunities men had (even then, scholarships usually covered only tuition, not the full ride of books and living expenses).

The first tournament was won by Immaculata, a small all-women school outside of Philadelphia that would win the next two as well. Home games featured nuns banging on buckets to create an unholy ruckus in a packed gym. Skirt-clad Grentz (the Rutgers coach, then known as Theresa Shank) was the team’s star, and the Coyle sisters, who grew up on the Main Line, were among its fans. The team sold buttons—WE’RE GOING TO BE NUMBER ONE WE TRY HARDER—to fund their trip to the tourney.

A few weeks before that tournament tipped off, Birch Bayh, a Republican from Indiana, introduced legislation on the floor of the Senate that would seek to eliminate the need for teams to sell tchotchkes to fund their travels. Title IX (at the time labeled Title X) would, of course, go down in history as a landmark statute, though no one involved with sports knew it at the time.

The vaguely worded act makes no mention of sports, and no one knew it would apply to extracurricular activities until the NCAA’s counsel thought to ask the question two years later. When the answer came back—yes—the NCAA sprung into action. And that action was to fight Title IX tooth and nail.

The worry was that forced funding of women’s sports would dilute men’s sports, especially football and basketball, which at most schools were the primary sources of athletics income. In 1974, John Tower, a senator from Texas, introduced an amendment that would exempt revenue-producing sports from Title IX. It passed in the Senate but was dropped in conference with the House. So in the summer of ’75—after three years of legal wrangling over Title IX’s enforcement—Tower introduced a bill with the same aims.

One of the statements entered into the record in favor of S.2106 was a letter from Nebraska football coach Tom Osborne, who wrote, “College football has a tradition that goes back 100 years and has evolved into a sport that has great spectator appeal. . . . It would seem logical that women’s athletics be allowed to grow and develop naturally along similar lines, in accordance with interest level, rather than to legislate into existence a large number of sports.”

Among the witnesses called to testify before the congressional committee handling the bill was a self-described “naive” 29-year-old recently hired by Texas as its first women’s athletics director: Donna Lopiano.

AIAW lawyers had called her because they figured she’d be able to get a hold of the Texas men’s athletics budget (which approached $2.5 million), as well as her own (which totaled $128,000 and was partially funded in part by proceeds from campus Coke machines).

When asked to testify, Lopiano’s initial reaction was, “My mother and father will be so proud.” Then the morning she was to leave she got a call from Lorene Rogers, the school’s new president and the first woman to hold that office. Lopiano thought it was going to be a get-to-know-you chat. It began more ominously: I understand you’re going to Washington to testify about Title IX.

“And the light went off,” Lopiano says.

She asked Rogers, “Are you saying I shouldn’t go?”

“No, no,” Rogers said. “I’m going to say how to keep your job.”

Rogers reminded her that Tower was the best friend of the chairman of the UT Board of Regents, and that it would behoove her to pay the senator a courtesy call. Lopiano was also to make it clear that she was not representing the views of the University of Texas. “I said I could do that,” Lopiano says. “She said, Have a good time. And I did.”

On the stand, Lopiano was far from naive. After beginning with the disclaimer that her views were her own, she attacked the bill’s under-lying assumption that an athletic department could not offer women a fair chance without cannibalizing the men’s programs. “Besides taking issue with the insinuation of my lack of administrative ingenuity,” she said, “I question whether this assumption is valid even under the most obviously discriminatory, unequal programs. For example, my situation at the University of Texas.”

The bill died in committee, but the NCAA filed multiple lawsuits in the three years before schools were required to be in compliance with Title IX. The last one was dismissed in 1978, at which point NCAA leaders realized they were going to have play ball with women’s sports. Also factoring into the NCAA’s thinking was the fact that the AIAW was proving that women’s sports were a viable TV commodity. (The ’80 women’s basketball title game would get better ratings than that year’s NBA playoff action.)

And so the NCAA began talk of staging its own women’s tournaments. Lopiano and the AIAW loyalists were steadfastly against the idea on the grounds that women’s athletics would be largely run by men for whom women’s athletics were not a priority.

There was, however, a faction of women’s administrators who wanted to join forces with the NCAA, citing its deeper pockets, better television connections and established infrastructure. “Eventually we’re going to have to get together,” Nora Lynn Finch, the women’s AD at NC State, said before the vote. “There are differences in rules now. The AIAW discriminates against women athletes because the NCAA allows men more in recruiting and scholarships.”

The ultimate showdown came in January 1981, at the NCAA convention at the Fountainbleu Hotel in Miami. The debate on whether the NCAA should hold championships for women was intense. Arkansas athletic director and football coach Frank Broyles spoke vehemently against the idea, calling the NCAA’s attempt to take over women’s sports a “blitzkrieg.” He likely just feared women’s expenditures would cut into his budget, but that didn’t matter to the AIAW crowd. “He wasn’t doing it for the right reasons, but that was all right,” Iowa director of women’s athletics Catherine Grant said years later. “We adopted him at that convention.”

The vote was a 124–124 tie. The recount showed that the nays had won 128–127. As Lopiano and her victorious allies met with writers, the pro-NCAA side came up with a plan. They realized that Cal had voted no at the urging of its women’s athletic director. When she left the room, the NCAA backers approached the Bears’ faculty athletics representative and convinced him to introduce a motion to reconsider.

The motion passed, and a new vote was called. Sensing the shifting winds, the delegates approved the measure by a count of 137–117. And that brought about one of the great ironies of Title IX: It indirectly led to women losing the authority to govern their own athletics.

Lopiano turned her attention to reforming the NCAA from within. “Athletes don’t take their ball and go home,” she says. (She stayed at Texas until 1992, leaving to head the Women’s Sports Foundation.) But the AIAW had no choice but to go into what Lopiano calls “lawsuit mode,” filing a futile antitrust suit against the NCAA as it planned what turned out to be the last basketball tournament it would stage.

The 1982 AIAW final four featured a pair of regional rivalries. Grentz’s Philly-heavy Lady Knights took on Villanova in the semis, while the Longhorns played Wayland Baptist, a small school in the Texas panhandle that was the most storied program in the sport’s history.

In the 1950s, a local businessman named Claude Hutcherson who owned an airplane company adopted the team, flying them all over to play. The rest of the teams at Wayland were known as the Pioneers; the women’s basketball team was called the Hutcherson Flying Queens. Recruits, often from rural outposts where commercial flights were rare, were dazzled by flights to visit the school. The Queens won 131 straight games from 1953 to ’58 and were still a force in the ’80s.

Their regional was in Berkeley. “Right before we went to California it had come out that we weren’t going to be able to go [to the] NCAA and we were gonna have to go NAIA,” former player Darla Armes Ford says. “My mom kept a scrapbook. THE GLORY YEARS ARE OVER FOR THE FLYING QUEENS is one of the articles I have.”

And there’s the second irony of Title IX. As more schools committed resources to women’s athletics, the early adopters, the often small, local programs that outhustled everyone else when that—and maybe a fleet of airplanes—was enough to win, lost their status. As the stage got bigger, there was no room on it for Wayland Baptist. Or Immaculata, which now plays in the NAIA. Or Cheyney State, the Philadelphia-area school—and the nation’s oldest HBCU—that reached that 1982 NCAA final. Two years ago, the school disbanded the team.

“It definitely is bittersweet,” Ford says. “The Queens had a lot of history in getting the women’s game to where it is now.”

Wayland’s chance to go out on top ended with a loss to Texas. Rutgers beat ’Nova to set up the final in front of a small but boisterous crowd at the Palestra, where the Coyle family hung a banner from the scoreboard that read welcome home. “We had come full circle,” Mary says.

The AIAW had a deal to televise its championship with NBC—until the network switched sides. On March 28, 1982, it aired the NCAA final. The Longhorns and Lady Knights game was not televised.

The night before the game, Mary, Patty and another local native, Jennie Hall, went to the Finnegan playground in Southwest Philly for old time’s sake. Mary ended up playing for two hours. “I think it was my way of dealing with the nervous energy,” Mary says. “Patty and Jennie just watched like, You better not get hurt or Theresa will kill you.”

The point guard came through unscathed, and in the title game, Mary ran the show and Patty dropped a career-high 30 points as Rutgers pulled away late to win 83–77. The Lady Knights were champs, and they didn’t care that it was of an organization that would soon be defunct. “AIAW had a lot of really good teams in it,” Patty says. “You know, it wasn’t like chopped liver.”

No champagne flowed, but the players had the next best thing. “It was so hot and I was just sweating like crazy, but walking back to the hotel from the Palestra, I remember just meeting up with friends and fans,” Patty says. “They gave me a beer.” Later that night, Grentz took the girls out to dinner at Bookbinder’s, a fancy restaurant, where she and her husband put the meal on three personal credit cards.

Before the Lady Knights left Philly, a couple of players handled one last piece of business. At the NCAA final in Norfolk, Va., they knew that Louisiana Tech had beaten Cheyney State, 72–62. They also knew that it had been a grueling year for the Cheyney coach, C. Vivian Stringer. In November she and her husband, Bill, had been told that their 1-year-old daughter, Janine, had spinal meningitis. She would never walk or talk and would require lifetime care. Stringer spent many nights sleeping in Janine’s room at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, being brought changes of clothes by an assistant coach.

The Rutgers players took a toy stuffed bear and went to the Children’s Hospital to visit little Janine and Bill Stringer, who had stayed home while Vivian was with her team. “It’s the camaraderie, you know,” Grentz says of her players’ visit. “The camaraderie between the teams and the women who were coaching—we had our own sorority. We were there to take care of each other, to support each other.”

More Title IX 50th Anniversary Coverage

• 50 Years of Title IX: How One Law Changed Women’s Sports Forever

• These Women Are Setting a New Standard for College Athletes

• Title IX Timeline: The Defining Moments of Women’s Sports