"It's Our Time"

In the bowels of what felt like a haunted house, at a defining moment for a city, a team and a franchise quarterback, the Indianapolis Colts looked to one man for salvation. As the players sat glumly in their RCA Dome locker room at halftime of the AFC Championship Game, reeling from a first half in which they'd fallen behind 21-6 to the New England Patriots, coach Tony Dungy strode among them, delivering a message that even the team's biggest star had trouble swallowing. "I'm telling you, this is our game," Dungy proclaimed, fixing his eyes on quarterback Peyton Manning, whose playoff struggles mirrored Dungy's own. "It's our time."

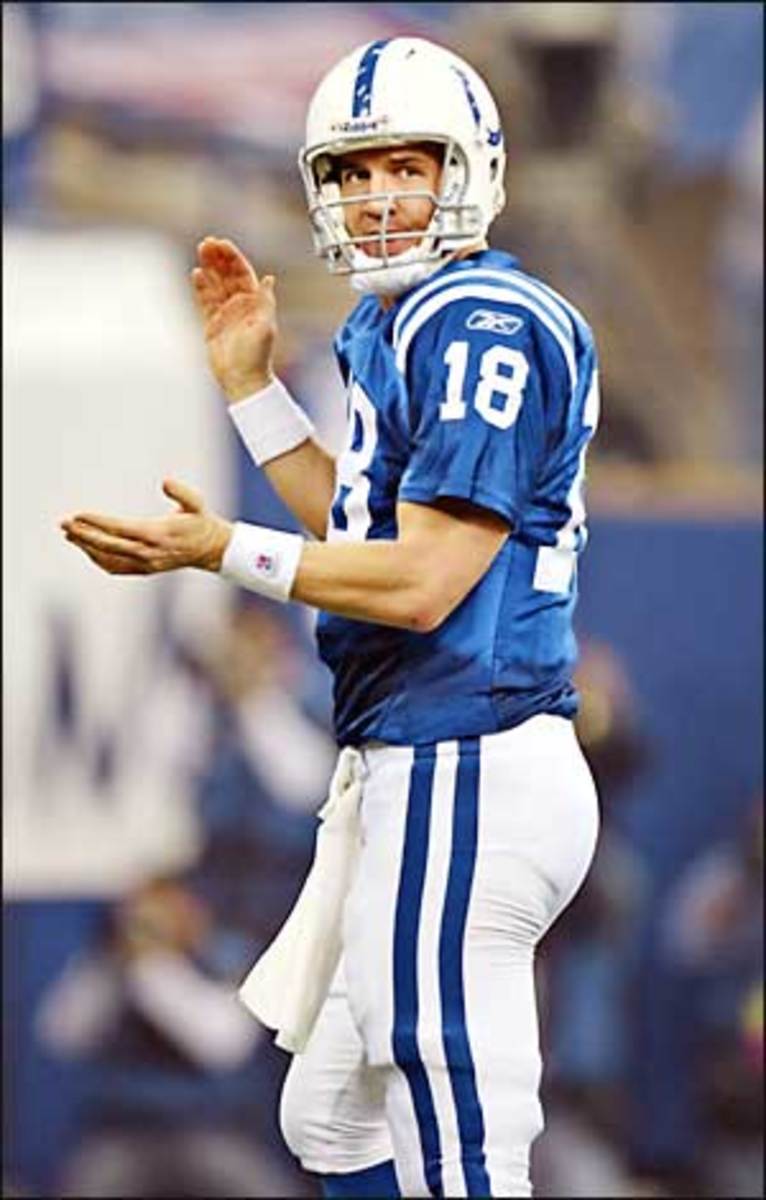

Dungy had uttered the same words the previous night as the team gathered at its downtown Indianapolis hotel, but now his optimism seemed unfounded. Manning, who before Sunday might as well have had can't win the big one tattooed on his forehead, was still obsessing over the 39-yard interception for a touchdown he'd served up to cornerback Asante Samuel, which had put the Patriots up 21-3 less than six minutes into the second quarter. It's our time? Had these words come from anyone other than Dungy, Manning would have tuned him out. "But Tony is one calm customer, no matter what the circumstance," the Pro Bowl quarterback said later, "and he has a way of making you believe. We're stressed out, and he's parading back and forth telling us we're going to win. That rubs off on the younger players, even the older players. It made a difference."

To credit a coach's demeanor for inspiring the biggest-ever comeback in a conference championship game and a historic trip to Super Bowl XLI would be overly simplistic, for Indy's thrilling, 38-34 victory required every bit of resourcefulness that this long-tormented team could muster. But it's true that everything the 51-year-old Dungy did at halftime, from his shrewd strategic adjustments to the perspective he provided, steeled a group of men who revere him at a time when abject panic was a couple of bad plays away. In return, with 30 transcendent minutes of football, the Colts claimed a triumph steeped in significance: They vanquished their archnemesis, a team that had twice humbled them in the postseason while winning three of the last five Super Bowls; Manning vaulted closer to the realm of the Pats' Tom Brady, his chief rival for supremacy at the sport's most glamorous position; and the franchise, which moved from Baltimore to title-starved Indy in 1984, earned its first Super Bowl berth in 36 years.

Oh, and this: The Ultimate Game just got a double dose of overdue diversity. When the Colts meet the Chicago Bears at Dolphin Stadium in Miami Gardens, Fla., on Feb. 4, Dungy and Lovie Smith, his close friend and former assistant, will make history as the first African-American head coaches to stand on a Super Bowl sideline. A man who appreciates the milestone's importance, Dungy smiled on Sunday as he watched the Bears take an 18-point lead over the New Orleans Saints in the NFC title game. Heading to the field for pregame warmups shortly afterward, he thought, Lovie's done it; now I've got to do my part. Dungy figured an 18-point deficit was insurmountable -- a notion, oddly enough, that his Colts would dispel a few hours later.

In a league of ultracompetitive jockeying and ulterior motives, few figures are as widely admired as Dungy, who despite being one of the most successful coaches of the postmerger era (a 114-62 regular-season record) had lost eight of 13 playoff games before Indy entered this postseason as a No. 3 seed. After reviving the once-pathetic Tampa Bay Buccaneers with an impressive six-season run as their coach, Dungy was fired before the 2002 season -- then saw his replacement, Jon Gruden, lead the Bucs to a Super Bowl victory. "[Dungy] built that team, and watching it win after he was gone had to hurt," Colts wideout Reggie Wayne said last Thursday night as he and 10 Indy defenders dined at an Indianapolis steak house. "We want to make up for that, and we know that this can be the first time an African-American coach is in the Super Bowl. We want to do that for him so bad, because he's like a father figure."

The players also are painfully aware of what the affable, deeply religious Dungy went through last season: In December 2005, Tony and wife Lauren's son James committed suicide at age 18. Tony missed the second-to-last regular-season game but returned after a weeklong absence. In its playoff opener top-seeded Indianapolis looked understandably distracted and suffered a 21-18 upset to the eventual champion Pittsburgh Steelers.

A little more than a year later Indy seemed to be replaying the Pittsburgh game, as the fourth-seeded Patriots caught the Colts napping in Naptown. New England took a 7-0 first quarter lead when Patriots guard Logan Mankins dived on the ball in the end zone after Brady and Laurence Maroney had mishandled an exchange from the Colts' four. (The football gods would return the favor early in the fourth quarter on a strangely similar play that bounced Indy's way, with center Jeff Saturday getting the star turn.) A seven-yard run by Corey Dillon put New England up 14-3, and two plays later Samuel jumped a sideline pass from Manning to wideout Marvin Harrison that hit the mute button on 57,433 fans. The Colts drove to the New England eight late in the half but settled for ex-Pats kicker Adam Vinatieri's second field goal.

The deficit called for adjustments, and Dungy and his assistants delivered. New England coach Bill Belichick, as is his custom, had devised a new wrinkle to throw at Manning, benching pass-rushing linebacker Tully Banta-Cain, shifting veteran inside backer Mike Vrabel to Banta-Cain's outside spot and giving third-year linebacker Eric Alexander his first career start. The move put Alexander, who's speedier than Vrabel, on tight end Dallas Clark and allowed the Patriots to disguise some of their zone coverages with man-to-man looks -- a ploy that helped Samuel bait Manning into throwing the interception.

But Dungy proved that his mind is as robust as his heart. "Belichick gets all the credit for training smart football players," says San Francisco 49ers backup QB Trent Dilfer, who played for Dungy in Tampa, "but Tony teaches football IQ as well as anybody in the NFL." Dungy's first move at halftime was to tweak Indy's predictable deployment of its Pro Bowl wideouts: Harrison on the right and Wayne on the left. Instead, the Colts sent Wayne into the slot, with third wideout Aaron Moorehead or Clark taking his place on the outside. This, said receivers coach Clyde Christensen, forced the Patriots out of their base 3-4 and into a nickel package that used a Cover Two scheme. With the corners playing press coverage, Clark and Wayne could exploit openings in the middle of the field.

Dungy also flashed back to one of his team's crushing losses to New England: a 38-34 home defeat in '03, when Indy trailed 31-10 before mounting a comeback that fell a yard short. "This gap is easier to close," Dungy told his players at the half. "We get the ball first, and if we score a touchdown on our first drive, we're only one score down."

Manning and the offense came out firing; he ended a 14-play, 76-yard drive with a one-yard sneak to make it 21-13. The Pats went three and out, and Manning mobilized once again, beginning with a 25-yard pass over the middle to Clark. The drive ended, improbably, on Manning's one-yard toss to backup defensive lineman and goal line fullback Dan Klecko. When Harrison made a terrific catch of a gorgeous Manning fade to the right corner for a two-point conversion to tie the game with four minutes left in the third quarter, it was time for the world's two best quarterbacks to step on the gas.

Gentlemen, start your spirals. Brady's willowy six-yard toss to wideout Jabar Gaffney in the back of the end zone put New England up 28-21. Manning answered by driving Indy to the Patriots' two, whereupon Saturday recovered running back Dominic Rhodes's fumble to tie the game. The two teams traded field goals before rookie Stephen Gostkowski's 43-yarder gave New England a 34-31 lead with 3:49 left. Each defense forced punts without allowing a first down, and when Manning trotted onto the field with 2:17 to go and the ball at his own 20, these were the stakes: Drive 80 yards and take a trip to Electric Bradyland; fall short and face at least another year's worth of chokes-under-pressure barbs.

Manning was on his game even before kickoff on Sunday, as his mother, Olivia, attested outside the Colts' locker room afterward. Noting that she and her husband, former Saints quarterback Archie, were celebrating their 36th wedding anniversary, Olivia gestured toward Peyton's older brother, Cooper, and his younger brother, New York Giants quarterback Eli, standing nearby. "Only one of my boys remembered," Olivia said, pulling out her cellphone to reveal a text message sent at 2:58 p.m. happy anniversary. i love y'all -- peyton.

On the most glorious drive a Manning quarterback has ever led, Archie was hiding in the tunnel behind the end zone, nervously sneaking peeks at the field. Peyton sandwiched completions to Wayne around a 32-yard deep out to third-string tight end Bryan Fletcher. Suddenly it was first down at New England's 11, and a pair of runs by rookie Joseph Addai set up a third-and-two at the three. The Pats typically blitz in such situations, but Dungy reasoned that they'd be hesitant because they'd been burned while doing so -- on a Manning fade to Harrison for a TD -- during Indy's 27-20 win in Foxborough in November. He was right. The Pats sat back. Addai took a handoff and blasted up the middle for the sweetest score any Colts fan has seen since Johnny Unitas hung up his high-tops.

Still, this epic wasn't finished until Brady, with 24 seconds to go and the ball at the Indy 45, zipped a pass over the middle toward tight end Benjamin Watson. Colts cornerback Marlin Jackson saw it like a neon light on South Beach. He raced in to make the interception that sent a choked-up coach and his jacked-up players to Miami.

Long after the confetti-laced celebration on the field, Dungy retreated to the dressing area and let his emotions flow. He talked of the inspiration he'd derived from James's memory and from the other parents of suicide victims whom he has befriended in the wake of his son's death. And he recalled the goodbye hug he got from Lauren on Sunday afternoon as he prepared to leave for the Dome.

"I want a blowout," she'd said, to which her husband replied, "It's probably not gonna be that way. It's gonna be a nailbiter." Then she clutched him tight and whispered, "No matter what happens, no matter what you do, I support you."

On this landmark Sunday, Lauren Dungy had more company than she could have known -- most notably from a locker room full of players whose leader refused to let them wilt. And really, why should they have? It was their time.

Issue date: January 29, 2007