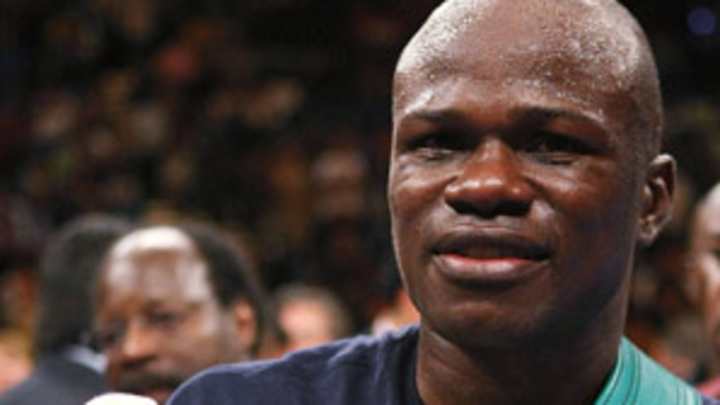

In losing Forrest, boxing lost one of its classiest champions

"See that?" he'd asked excitedly.

"See what?" I'd asked, confused, since no one had gotten hit, much less hurt.

"Watch again. Look close. When I reverse, Shane gets his feet tied up."

And a few sequences later: "Oh, see that!"

"No. What?"

"Look how his elbow drops when I lead left."

Forrest was a fighter's fighter, a self-described purist, who embraced the sport's nuances and geometry. Though lanky and wiry strong, he was much more likely to win a fight by outflanking his opponent than by beating the crap out of him. "The goal of boxing," he explained, "isn't just to bust the other guy up."

Forrest was a member of the 1992 U.S. Olympic team -- beating out Mosley, ironically enough. He was undefeated for the first decade of his pro career. In his prime, he was a contender for boxing's mythical title of the world's best pound-for-pound fighter. But his profile was modest, the sad fate of a contemporary fighter who simply does his job honorably. No flash. No concussive knockouts. No shtick. Even his obligatory nickname, "The Viper," never took hold. "Sometimes I wish," Forrest said, "I had come along in the '50s."

He was atypical in other ways, as well. Forrest grew up in Augusta, Georgia -- not the azalea Augusta we see during the Masters telecasts, he was quick to point out -- no boxing hotbed. He had moved to Atlanta, but lived in a quiet southside suburb where he mowed his own yard and grilled with the accountant and lawyers on his block. When he wasn't boxing, he was running Destiny's Child, a group home for mentally retarded adults. Technically, it was a business. He received a fee from the state for every boarder. But clearly it was philanthropy. When he went to the facility, Forrest was swarmed by grown men, and hugged them all. They all had stories about how Vernon -- never "Mr. Forrest" or "the champ" -- engaged them in water-balloon fights or cooked breakfast or took them to job interviews.

On my second day with Forrest, he met Shirley Franklin, the mayor of Atlanta, for one of those key-to-city presentations. She expected a quick photo op with an athlete; she did not expect to be pressed on her commitment to various social programs. Forrest figured so long as he had an audience, he might as well speak his mind. "Was that OK?" Forrest asked later. "Was I too aggressive?"

For as often as we hear about "senseless killings," the cold-blooded murder of Forrest, shot to death Saturday night after an apparent botched carjacking, might set a new standard. Here was a saint of a man, gunned down over nothing. And this murder was as ironic as it was tragic. Here was the rare boxer who had little use for violence, killed in the most brutal way imaginable. Here was a champion of Atlanta, killed on its streets. Here was a man who cared deeply about boxing's portrayal, yet his death will represent still another threat to its well-being.

Forrest joins Alexis Arguello and Arturo Gatti as the third champion to die unexpectedly in the past month. Never mind the dearth of dynamic figures, the usual sanctioning body nonsense, and the rise of the UFC -- when even the most decorated champs die young, that's an image problem.

But, like Arguello and Gatti, Forrest represented what was right with boxing, not wrong with it.

In his rematch with Mosley, Forrest was, again, the technically superior fighter and won a decision. He got the HBO deal and life was good. But in his next fight he faced Ricardo Mayorga, a Nicaraguan who was everything Forrest wasn't: unorthodox, undignified, uncaring. Mayorga was known to puff cigarettes between rounds when he trained. The night before fighting Forrest, he was spotted at the blackjack table and allegedly fell asleep on the casino floor. He then won the fight. And the rematch.

Forrest then disappeared. He had injured his arm and was undergoing surgery, but it went beyond that. He'd studied and trained and lived like a monk, and had lost to this brawling madman. His trust in the sport has been broken.

Forrest, though, eventually returned, repairing his record and confidence in equal measure. By 2007, he'd claimed another belt, the WBC light middleweight title. Last fall, at 37, he beat Sergio Mora and was angling for one last big-money fight, perhaps against Kelly Pavlik.

There are some athletes who die young and, while it's unmistakably tragic, it's not altogether unexpected. As a fighter, Forrest won with savvy and professionalism, not incapacitating force. But his death is a hell of a blow.

AP: Forrest killed in apparent robbery

VAULT:Forrest wins belt, but was already a champ (7.29.02)

Jon Wertheim is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated and has been part of the full-time SI writing staff since 1997, largely focusing on the tennis beat , sports business and social issues, and enterprise journalism. In addition to his work at SI, he is a correspondent for "60 Minutes" and a commentator for The Tennis Channel. He has authored 11 books and has been honored with two Emmys, numerous writing and investigative journalism awards, and the Eugene Scott Award from the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Wertheim is a longtime member of the New York Bar Association (retired), the International Tennis Writers Association and the Writers Guild of America. He has a bachelor's in history from Yale University and received a law degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He resides in New York City with his wife, who is a divorce mediator and adjunct law professor. They have two children.

Follow jon_wertheim