Draymond Before Draymond: The Complicated Legacy of Dennis Rodman

When you hear Dennis Rodman’s name, what—or more accurately, who—do you think of?

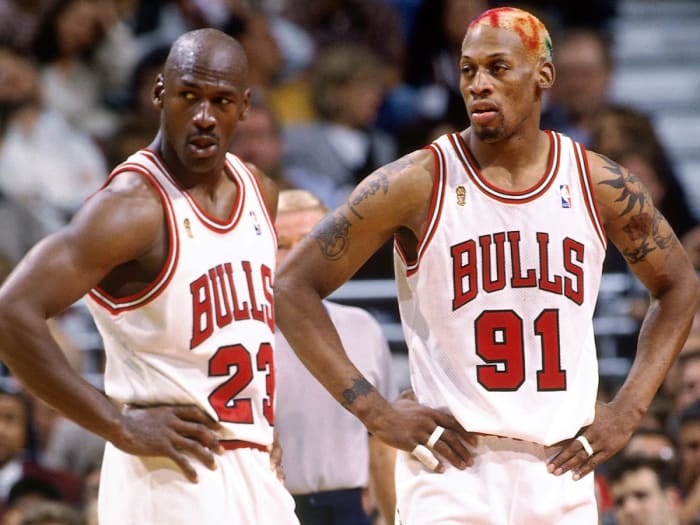

Perhaps you remember Rodman the basketball player. That man—tireless, relentless, owner of elite basketball IQ—sprinted off the Delta Center Court 20 years ago this month, arms raised, having logged 39 minutes in the Bulls’ clinching Game 6 NBA Finals win over Utah, the last title of the Jordan era. Despite coming off the bench, the 37-year-old Rodman was the primary defender on Karl Malone and led the playoffs in rebounds.

At the time, Rodman was considered an outlier, for what other 6’7" forward could pull down 20 boards and defend both point guards and centers? Now he instead seems ahead of his time, a wiry preview of the modern NBA: a long, heady defender capable of switching any matchup; a big who could lead the break; an intuitive passer and screener. He was, in many respects, Draymond Green before Draymond Green, down to his ability to infuriate opponents (something Green has done with delight during these playoffs).

The similarity isn’t lost on the Warriors, who are in the midst of establishing their own superteam legacy. Steve Kerr first mentioned it during his inaugural season as coach in 2015, at the dawn of Golden State’s small-ball era. Green, he noted at the time, “has a lot of Dennis Rodman in him,” citing how he “defies positions,” “guards anybody,” and “rebounds like crazy.” Had Dennis been able to knock down threes—something Chuck Daly and Phil Jackson occasionally let him do as a reward for all those rebounds—he’d have fit perfectly in 2018. “What he did was so unique and incredible and different,” Kerr says after a Warriors practice. “I’ll never forget it.”

Then again, Kerr was on that Bulls title team. He lived it.

But that was 20 years ago now. These days, basketball’s not always the first thing that to comes to mind with Rodman.

“My next guest is a five-time NBA Champion, a Hall of Famer and..."—Stephen Colbert pauses—"possibly all that is standing between us and thermonuclear war with North Korea!”

This is six months ago. Rodman, now 57, ambles onto the set of Colbert’s show, wearing cargo pants and a T-shirt that reads “Potcoin,” which, he explains, is a “cryptocurrency…or something like that” dedicated, he explains, “to legalizing marijuana.” The shirt, which still bears creases from being hastily put on, features an image of Donald Trump, Kim Jong-un and Rodman, superimposed over the American and North Korean flags and above the word UNITE.

After the requisite banter, Colbert turns serious, asking about Rodman’s five trips to North Korea since 2013.

Have you spoken to Kim Jong-un about his nuclear program at all?

Have you said, “Please don’t start a nuclear war?”

Have you spoken to him about human rights?

Rodman eludes. Rambles. Veers. “I don’t really judge people by their color,” he says. “I don’t judge where they come from…we all human beings, you know?” And: “Well for some reason he likes me. I’m being honest, he likes me.” And: “I don’t discuss politics [with Kim] because that’s not my job…my job’s to be a human being.” Colbert’s responses range from incredulous to dismayed to horrified.

Throughout the seven-minute interview, Rodman wears sunglasses, as he does for pretty much all public appearances these days. He’s clearly more interested in hawking his sponsor than engaging with the audience or Colbert. Most distressing, he displays a stunning ignorance of the political reality and dangers of North Korea. At one point Rodman tries to defend Kim as being just a regular guy and Colbert responds by noting that Kim murdered his own uncle (Rodman seems surprised). Dennis ends the interview by trying to get Colbert to wear a T-shirt with his own face added to the Kim-Trump-Rodman triumvirate. Responds Colbert, for the second time in the interview: “You. Must. Be. High.”

In the months that follow, as a potential Trump-Kim summit stays in the news, Rodman, a longtime friend of Trump’s, goes on BuzzFeed and then TMZ, hoping to take preemptive diplomatic credit for any potential positive outcome. Or at least stay in the spotlight.

Sadly, none of it is all that surprising. The post-basketball version of Dennis has spent two decades squandering his money, drinking himself in and out of rehab, and making desperate pleas for attention (This 2013 Sports Illustrated story is a good primer).

With each passing year, his legacy further blurs. It’s easy to forget that in his own way he was once something of a trailblazer—intentionally or not—for gender identity and acceptance in sports, the rare man in the structured culture of professional athletics who encouraged people to let their freak flag fly. Just as it’s easy to forget how revolutionary he was as a player.

Imagine double-teaming someone who rarely, if ever, scores. Now imagine doing it even if he doesn’t have the ball.

Such was the strategy Pacers coach Bob Hill resorted to in an effort to slow down Rodman in 1992, during his record run of seven consecutive seasons leading the league in rebounds. Not the easy, missed free throw kind either. Rodman terrorized teams by sprinting in from the perimeter on offense, hurtling in and tipping and tipping to himself before kicking it back out. The night he grabbed 34 boards, in March of 1992, eighteen were offensive. As Scottie Pippen once said of playing with Rodman, “It felt like we were always on offense.”

Hill couldn’t stand it. “Every time he did it it’d piss you off. It’s on the board [in the locker room], it’s in the walk through. Put a body on him, faceguard him, knock him down! And he still got the ball!” So instead Hill assigned two forwards—Detlef Schrempf and LaSalle Thompson—to double Rodman when a shot went up, hoping it would throw a wrench in the Pistons offense.

How did that work out?

Says Hill: “It didn’t. He was too active and too strong.”

The same way Jerry Rice ran every route as hard as possible even when he knew he wasn’t getting the ball, Rodman chased every shot. Try for nine and he’d get the 10th, he figured. He studied ball flights and angles, and possessed an uncanny ability to gauge caroms. Like Wayne Gretzky, he felt he could see two seconds into the future.

Leaning on LeBron: Can the King Carry the Cavs Again in Game 3?

His ascent was almost as unlikely as his backstory. Rodman’s father left home when he was three. Short and awkward, he didn’t play basketball in high school, and was working as a night janitor at Dallas/Fort Worth airport when a nine-inch growth spurt changed his fortunes. After one semester at junior college, he landed at Southeastern Oklahoma State, an NAIA school, where, as a senior he eventually averaged 24.4 points and 17.8 rebounds. In 1986, the Pistons took a chance on the 25-year-old in the second round of the draft.

He made an immediate impression. “I’d try to kick his ass and punk him as much as I could in practice,” recalls Rick Mahorn, the incumbent power forward. “You got a young guy with a lot of ability that's trying to get your minutes. But he didn’t back down. Our practices were so intense that the games were easy.”

By the 1990 season, Rodman was starting. Two years later, he averaged 18.7 rebounds, a number no one (other than Rodman) has come close to in the 28 years since. (Only Kevin Willis, Ben Wallace, Kevin Love, DeAndre Jordan, and Andre Drummond have averaged more than 15, and none have topped 16.)

Back then, before Madonna, multi-hued hair and all the rest of it, coaches and teammates recall Rodman with fondness. Mahorn tells of coming into the locker room and finding Rodman crying. “We’d just won a big game in Boston and I realized it was tears of joy because he was so glad and humbled that he was playing in the NBA.”

Brendan Suhr, an assistant coach for the Pistons and head scout for the 1992 Dream Team, calls Rodman, “The smartest player I ever had, and I’ve had 13 in the Hall of Fame.” Says Suhr: “No matter who was on the other team, [Rodman] could tell you the strengths and weaknesses of every player. Not because we had it in the scouting repot. He studied them.”

Bill Laimbeer remembers being shocked by Rodman’s athleticism. “I always thought Dennis would have been an Olympic champion in the 220 or the hurdles,” says Laimbeer. “I’ve never seen a basketball player faster than Dennis. He had a gear, like a Carl Lewis or Usain Bolt, where all of sudden he kicks it in and everyone was left in the dust.” According to Mike Abdenour, the Pistons trainer at the time, Chuck Daly actually suggested to Rodman that he go to the U.S. track and field qualifiers. “Chuck said, 'Maybe you should go qualify for the 400,” says Abdenour. “There’s no doubt in my mind that with that stride length he could have done it. He had tremendous acceleration.”

The Pistons utilized that speed in creative ways. “When Pitino came in with the Knicks, he would press teams and drive them crazy,” recalls Suhr. “But in all of Chuck’s offenses, if they trapped Isiah [Thomas] and Joe [Dumars] in the backcourt we’d throw it to Dennis and he’d dribble it down as fast as any point guard in the league. And he could really pass the ball. The only reason he didn’t score more was he didn’t want to. He was a very unselfish player.” (It helped that Rodman never got tired; during the 1992 season the Pistons at one point played four games in five days and Rodman logged 47, 48, 47, and 48 minutes).

Then there was his defense: annoying, ever-present, utilizing his deceptive strength and leverage. When Suhr later wrote a book describing the Pistons’ “Jordan Rules,” Michael ended up reading it while visiting one of Suhr’s practices (the two knew each other from the Dream Team). Says Suhr: “And then he came over and said, ‘F--- these Jordan rules. There were no Jordan rules. You just put Rodman on me!”

To many, the Bad Boys version of Rodman is the one they choose to remember. As Mahorn puts it: “I don’t know Dennis. I know Worm.”

And then it all changed.

“Rare Bird,” read the cover of the May 29, 1995 issue of Sports Illustrated. It’s difficult to appreciate now just how impactful the accompanying image was: a prominent black athlete on the cover of a national magazine, wearing only a rhinestone dog collar, short leather shorts, a shiny vest and, for good measure, holding a blue parrot.

The story, written by Michael Silver, was unlike any that had come before in the magazine, or likely since. Silver had flown to Los Angeles before Game 6 of the Spurs-Lakers conference semifinals, hoping to get Rodman to open up. That night, after a series-clinching win, Silver found himself at a club in Beverly Hills with Jon Lovitz and Rodman. “Dennis was just starting to get weird, and I knew he was supposed to be a guy who could drink,” recalls Silver. “I’m like, ‘I’m 29, he’s 34, I party pretty hard. I can hang with one 34-year-old for one night. It’s not going to be a problem.’” Silver pauses. “Cut to me pouring shots out under the table—and they’re all the girlie shots like kamikazes. I’m like holy s---, freak of nature!”

A three-day odyssey ensued: a late-night flight to Vegas (Pearl Jam blaring on the plane, craps, strippers, booze); a night at a gay bar (more booze); a near-showdown with then-Spurs GM Gregg Popovich (shockingly, Pop preferred Rodman be with the team rather than staying in Vegas in advance of the conference finals); and, finally, a sleepless Saturday night at Rodman’s house, Silver typing out his story on a bulky laptop surrounded by squawking exotic birds while Rodman entertained himself with strippers.

Silver filed Sunday. In New York, SI editors deemed one quote too risqué to include. As Silver recalls, “Dennis told me, ‘If I ever do decide to love another man, I’m going to find one just like me and love the s--- out of him, it’s going to be like two bulls going at it, bro. I promise you that.’” (When Silver warned of the potential response to such a quote: “Dennis said, ‘Yeah, but it’s going to make me a f---load of money.’”)

When Silver’s story came out, it nearly overshadowed the conference finals. Talk radio went nuts. Newspaper columnists weighed in. “The beginning of the end,” wrote a concerned Mitch Albom. “RODMAN ROBS GAME OF VALUES,” read the Seattle Times headline. “RODMAN: CLOWN OR MONSTER?” asked the Miami Herald. Rodman eventually appeared on Letterman. The attention nudged him ever further toward his new stated goal: to exist as “an entertainer” rather than a basketball player.

At the same time, the story had a galvanizing effect on the LGBTQ community. This was two decades before Jason Collins. Rock stars like David Bowie and Freddie Mercury had played with gender identity but little precedent existed in the world of major men’s sports. And now fans were reading quotes like this, from Rodman: “Everybody visualizes being gay—they think, 'Should I do it or not?' The reason they can't is because they think it's unethical. They think it's a sin. Hell, you're not bad if you're gay, and it doesn't make you any less of a person.''

Silver witnessed the effect. “[Dennis] lived most of his life scared to show his weirdness,” says Silver, who remained close with Rodman, writing the second of his four memoirs. “Once he showed it, he was so overwhelmed by how many people came out of woodwork to support him. All the freaks, and that’s a broad definition, anyone who’s freaky in any way, he was their hero for speaking out. And he got all this positive reinforcement he hadn’t seen coming. He was surrounded by other artists, people that didn’t fit in, whether transgender or people who lived on the fringes.”

In retrospect, Rodman had a remarkable platform. He could have become an advocate or cultural ambassador. That wasn’t his style though. “Dealing with Dennis is like dealing with your best friend when you're 10 years old,” says Silver. “There's nobody better. You love that guy. It’s beautiful. But sometimes when you need to have an emotionally developed interaction or a logistically important interaction, it’s like, I’m dealing with my best friend when I’m 10.”

When I ask Kerr, in retrospect, if Dennis might have been something of a trailblazer, he pauses. “Once I got to know him, I realized that a lot of it was just shocking people,” says Kerr, one of a handful of teammates who kept in touch with Rodman. “I think Madonna taught him a lot about marketing and the value of shock. It was not only good for his brand but he just liked to stir it up. Whether that made people more comfortable with transgender issues, I don’t know. I don’t think so. I would say no. I think the key moment is Caitlyn Jenner for the transgender world.”

Kerr pauses. “I think Dennis was just being Dennis.”

In 2000, Rodman retired after a final truncated season with the Mavs. In a different universe, a player with his basketball IQ might have become an analyst, coach, or guru, dispensing wisdom. Like Barry Bonds, A-Rod, and other prickly athletes who eventually made the switch, you imagine Rodman has a lot to share.

Instead, well, you know the story: Celebrity Apprentice and the Lingerie Bowl and police blotters. When Rodman became eligible for the NBA Hall of Fame, in 2005, he didn’t make the list of finalists, despite those five rings, two All-Star appearances, and seven All-Defensive First Team selections. Neither did he make it the following year, or the year after that, or the one after.

What's LeBron's Best Option This Summer? Debating 10 Teams and One Crazy Idea

As voters ignored him, however, another community was reassessing Rodman. In the 10 years since his retirement, the NBA analytics revolution had taken wing. New terminology took hold: Player Efficiency Rating and rebound percentage and on/off-court metrics. And so, in 2010, an amateur quantitative analyst named Ben Morris, who was making a living at the time by exploiting data sets in online poker, set out to prove a theory he’d long held: that Rodman, whose game he’d long admired, was more valuable than people realized.

Over a series of 12 posts on his blog, Morris made what he termed “The Case for Dennis Rodman”. You should read the whole thing—it’s fascinating, even seven years later. He began by stating that Rodman’s rebounding ability was, “substantially underrated” calling him, “unquestionably—by a wide margin—the greatest rebounder in NBA history.” By using a variety of statistical measures, Morris proceeded point-by-point, offering comparisons—“Kevin Garnett’s career rebounding percentage is lower than Dennis Rodman’s career *offensive* rebounding percentage”—and rebutting the assumption that Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell were superior at the craft. Wrote Morris: “Due to the fast pace and terrible shooting, the typical game in 1960-61 featured an average of 147 rebounding opportunities. During Rodman’s seven-year reign as NBA rebounding champion (from 1991-92 through 1997-98), the typical game featured just 84 rebounding opportunities. Without further inquiry, this difference alone means that Chamberlain’s record 27.2 RPG would roughly translate to 15.4 in Rodman’s era—over a full rebound less than Rodman’s ~16.7 RPG average over that span.”

Morris spent over a year, on and off, on the research and posts. By the end, he made a bold claim. “Now, to be completely clear, as I addressed in Part 3(a) and 2(b), so that I don’t get flamed (or stabbed, poisoned, shot, beaten, shot again, mutilated, drowned, and burned—metaphorically): Yes, actually I AM saying that, when it comes to empirical evidence based on win differentials, Rodman IS superior to Michael Jordan. This doesn’t mean he was the better player: for that, we can speculate, watch the tape, or analyze other sources of statistical evidence all day long. But for this source of information, in the final reckoning, win differentials provide more evidence of Dennis Rodman’s value than they do of Michael Jordan’s…. If the 5 championships, the ridiculous rebounding stats, the deconstructed margin of victory, etc., aren’t enough to convince you, this should be: Looking at Win% and MOV differentials over the past 25 years, when we examine which players have the strongest, most reliable evidence that they were substantial contributors to their teams’ ability to win more basketball games, Dennis Rodman is among the tiny handful of players at the very very top.”

In 2011, Rodman finally gained acceptance to the Hall of Fame, giving a tearful speech in which he promised to be a better man, husband, and father (he has three children, two of whom are currently promising high school athletes). Two years later, Rodman publicly thanked Morris, tweeting, “Really cool analysis of my career by my boy Benjamin Morris,” while leaving a comment on Morris’s site that read, in part: “I can honestly say I’ve never seen my numbers broken down this way” and ended “much love honey.”

In the years since, Morris, who now works for FiveThirtyEight.com, says he still hears from people who read the posts. Each time Rodman surfaces in the news again, he gets a traffic bump. “I think people start searching trying to find out why we’re talking about this guy.”

Morris wonders if it’s all related. “People say he’s crazy now but maybe he never was sane,” he says. “If he’d been sane, would he have been the same basketball player? I don’t know. Maybe he would have tried to play a conventional style and been good, but maybe he wouldn’t have won five championships and made so many teams a contender.” Indeed so much of what Rodman did—the piercings, the hair, the tattoos, choosing jersey No. 91, refusing to shoot and bailing on practice and all the rest—fit with his contrarian nature. “Maybe,” Morris says, “that’s exactly what made him great.”

Like Morris, I always had a soft spot for Rodman the player. As a teenager watching those Pistons and Spurs teams, I didn’t care if Dennis couldn’t—or didn’t—shoot. He understood the game, and how to win, like few others. He was unselfish and relentless. He made you believe that if you just wanted it more than the other guy, that’s all that mattered. I wanted that Dennis to endure.

So, a few months ago, I headed to a Warriors practice to talk to Draymond Green. I’m not sure what I expected him to say. I guess I hoped to hear that Green had patterned his game after Rodman’s. Or maybe watched old film to uncover tricks of the trade. That a direct line existed between him and the Worm, between those Bulls and these Warriors.

"Rodman?” Green paused for a second. I could see him considering what to say. Green, as you probably know, is an unfailingly good quote: smart, funny, candid, profane. It can seem at times as if it’s just one more way he can compete with his contemporaries—I’ll beat you at the quotes too.

This time, though, he lacked a ready opinion. Finally he offered: “He made an entire living off playing hard and outworking his opponent and I appreciate anyone who does that.” He called Kerr’s comparison, “an honor.”

More probing followed but Green deferred. “To be honest, I modeled myself more after Ben Wallace,” he said. “I never really watched Dennis.” And, despite the similarities, Green does differ from Rodman in important ways: a locker room leader rather than, at times, a divisive loner (Rodman referred to David Robinson as “Most Valuable P----”), a player who fuels his team, and a more well-rounded offensive player.

Indeed, while players still occasionally mention Rodman—including Kawhi Leonard, Tristan Thompson, and, most recently, Warriors guard Nick Young, who said he dreamed about Dennis during these playoffs, Green’s relative indifference shouldn’t be surprising. While Pippen holds forth on ESPN and Jordan’s legend grows in retirement, Rodman has done little to remain relevant to the basketball community. Plus, as Kerr points out: “It was 25 years ago. Whatever happened 25 years prior to that, people probably forgot too. It’s just that everything tends to fade with time. But those of us who played in that era certainly don’t forget.”

Kerr last saw Rodman during the 2017 playoffs. Silver has spoken to him on and off the last couple years, including when he got out of rehab this spring. “The most lucid I’d heard him in a while,” says Silver. “He was taking about Korea. He said, ‘I know I’m being used…I know what he’s doing.’ He said ‘You gotta trust me, if you saw how cut off these people are from the world, I still think it’s worth it, the way we’ve been able to open their eyes.’” (The conversation ended the way all apparently do with Rodman: with Dennis hanging up abruptly.)

Like many, Silver always appreciated Rodman’s earnestness—and Dennis is often described by those who know him as good-hearted, if naïve and self-destructive. Silver hopes it goes well for his friend. But he knows there’s little he can do.

“At one point, early on, I remember it was late and we’re hanging out and he said, 'Bro, I know I’m going to blow the money. I know it’s going to end bad. I know what everyone says, they look at me and say he’s a trainwreck and he’s going to blow it all and it’s going to be sad at the end.’ I know all that. But if you understood where we were when this all started, and how crazy this all is that we even made it out of that shitty town in Oklahoma and we’ve lived this life we’ve lived and all the good times and all this s---. Hey, if we blow the money, we blow the money.”

It’s an ongoing challenge in sports: How do we separate—can we separate—the athlete from the human being? Is it possible to appreciate elements of Kobe Bryant—the competitive instinct, the work ethic—and also remain horrified by his rape case? Can we respect Barry Bonds’ swing and also deem him a first-rate prick?

When I began work on this story, some time ago now, I debated whether or not to try to talk to Rodman. After all, it’s usually what you do when you write about someone. Then I looked back at his quotes the last time he spoke to SI, in 2013. A representative one: “If you ranked the 10 most identifiable people on the planet, I'd be Number 5….I'd come in right after God, Jesus, Muhammad Ali and Barack Obama.” The next column SI ran, by Michael Rosenberg, summed him up thusly: “Dennis Rodman is a desperate and pathetic character who will do anything to get noticed.”

More recently, in 2017, the Washington Post described Rodman’s post-basketball life as “a string of legal troubles, voluminous alcohol consumption and trading off B-list fame,” noting how “in 2012 he allegedly owed more than $800,000 to his ex-wife and the mother of two of his three children. In legal filings, his representatives responded by saying he was broke and unable to pay, his alcoholism having sapped his corporate marketing opportunities.” That same year, CNN reported on a petition to remove Rodman from the Hall of the Fame citing his “coddling” of Kim. (This is part of what frustrates those in the political community. As easy as it is to dismiss Rodman’s trips, he’s been granted unique access.)

His contemporaries don’t get it. “I always worry about him a little bit,” says Bob Hill. “I don’t know anything about his life or his habits now. He did like to drink. I always worried that he’d get in a car accident. Why he went to North Korea, I have no idea. Publicity? Money? The real guy was the one that played so hard every day. We need guys like him in the league.”

“I love the guy,” says Mahorn. “But when the business of basketball comes, it usually messes people up.”

“I think he’s misunderstood,” says Tom Thibodeau, an assistant during Rodman’s time in San Antonio. “He had a big heart. He was the first guy I was around that, after a game, would go and do another full workout. And who knows what he did after that…Some of the off-court stuff was obviously over the top but when you watch the way he played the game…” And here Thibodeau trails off, one defensive aficionado reminiscing about another.

Abdenour says he still hears about Rodman via emails from old friends. “They say Dennis is still Dennis, he’s surviving," says Abdenour. “He’s a guy who could be part of the Walter Mitty society. Doesn’t care about a whole lot, enjoys life.” He pauses. “But the drummer he’s listening to, it’s not a beat I can hear.”

In my case, I choose to leave Rodman in the past. Hold our youthful heroes up to the light and we’re bound to see all the cracks and imperfections, and in Rodman’s case there’s a lot to see. Sit for an interview and he’d probably look for an angle or try to sell something. (On his website, among other offerings, Rodman sells customized, signed basketballs for $1,200.) Chances are, others can better tell his story at this point, anyway. So why not appreciate who he was, not who he’s become. Maybe it’s even possible to separate the two, the same way music fans might do with Kanye West.

In the week ahead, with the June 12 North Korea summit looming and another Warriors title appearing likely, Rodman’s name will continue to surface, in bizarrely different contexts. Yesterday, the New York Post reported that he will be in Singapore for the summit, and suggested he might even play a role alongside Trump. Let that marinate for a moment.

With each successive mention, a choice will exist. Which Rodman should we remember? The one whose legacy is authored by TMZ or by people like Ben Morris? Green knows which he prefers. “I know basketball,” he says. “I don’t get off into politics. I don’t think of [Rodman] as the guy who went to North Korea.” Green pauses. “I just look at him as Dennis Rodman, world champion, Hall of Famer.”

I’d like to think I can do the same. But it’s not getting any easier.