Legal issues raised by Falcons asking prospect if he likes men

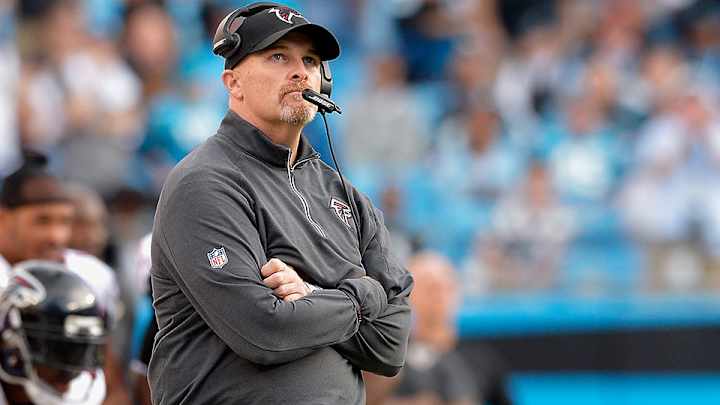

In the latest example of an NFL team representative improperly asking a prospective NFL player about his sexual orientation, Ohio State cornerback Eli Apple revealed on Friday that an Atlanta Falcons coach asked him, “So do you like men?” The question was posed during last month’s NFL combine in Indianapolis. Falcons head coach Dan Quinn, on behalf of his coaching staff, has apologized to Apple, who is a projected first-round pick in next month’s draft. This situation is reminiscent of University of Colorado tight end Nick Kasa being asked if he “likes girls” prior to the 2010 NFL draft and of players complaining of similar types of questions leading up to the 2013 NFL draft.

The NFL clearly prohibits teams from asking players about their sexual orientation, among other topics that implicate privacy interests and that are irrelevant to someone’s ability to play football. The league, in fact, has adopted a set of sexual orientation anti-discrimination and harassment policy guidelines as part of its Excellence in Workplace Conduct program. To illustrate, NFL team officials are barred from asking players such questions as, “Do you like women or men?” or “How well do you do with the ladies?”

Falcons apologize for asking draft prospect Eli Apple if he likes men

The NFL’s internal guidelines are not the only source of law that forbids teams from asking players about their sexual orientation. Although federal law does not bar sexual orientation discrimination by private employers, the Human Rights Campaign finds that 22 states and Washington, D.C. impose this prohibition. There are also numerous counties and cities, including Atlanta and Indianapolis, that impose related prohibitions through ordinances. Given that the NFL combine is in Indianapolis and given that nearly all teams play home or away games in jurisdictions that prohibit sexual orientation discrimination, all NFL teams could be vulnerable to litigation if their coaches and scouts discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. New York attorney general Eric Schneiderman made this point clear in his March 14, 2013 letter to NFL commissioner Roger Goodell. Schneiderman demanded that the NFL prevent employment discrimination in the recruiting process.

The issue of sexual orientation discrimination in the NFL is also addressed in the collective bargaining agreement signed by the NFL and NFLPA. Under Article 49, any discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin or sexual orientation against a player is prohibited. As this prohibition is broadly worded, it should allow the NFL to punish a coach or scout that subjects a player to homophobic taunts, derogatory insults or inappropriate lines of questioning. It could also be interpreted as requiring NFL teams to remove fans from stadiums who heckle a player on the basis of sexual orientation. Article 49 garnered some attention after University of Missouri defensive end Michael Sam, who is openly gay, was drafted by the St. Louis Rams in the 2014 NFL draft.

Did Article 49 protect Apple prior to the draft? This question is important because it highlights the unclear role of the NFLPA at the combine, an event featuring NFL teams and college players. The NFLPA, keep in mind, is “the union for professional football players in the National Football League.” It is not the union for college football players or amateur football players. This would seem to be true of those who try out for NFL teams.

Further muddling the analysis of whether the NFLPA protects players at the NFL combine is determining when exactly one becomes an NFL player and thus an NFLPA member. The earliest possible point in time would be when an amateur player attends the combine and works out for, and interviews with, NFL teams. This is clearly a “professional” experience. Then again, activities at the combine better resemble a tryout than a job—especially since many of the players at the combine won’t ever have NFL careers. A player at the combine is also not a member of any NFL team and is thus not paid by any NFL team. The player’s agent, in fact, often pays for the player’s expenses at the combine. This player also has no influence over the NFLPA because he is not a voting member of the NFLPA. A player at the combine therefore seems more like a job applicant than an employee.

A later possible moment when a football player becomes an NFL player would be when that player is drafted. At that moment, the player’s employment rights to play in the NFL are exclusively assigned to one NFL franchise. He is not yet paid by an NFL team but is paired with that team.

An even later point in time would be when that drafted player signs a contract with an NFL team and begins receiving compensation. Signing a contract and/or receiving pay are often thought of in the U.S. workplace as signifying when one becomes an employee.

The latest possible time would be when a player actually appears in an NFL game. Until then, his stat sheet has “0s” across the board.

At first glance, then, it would seem that Article 49 would not protect a player at the combine. The NFLPA might therefore not have a suitable role at the combine to protect the interests of players.

This view may miss the mark for two reasons.

First, the NFLPA licenses and regulates the agents who represent players at the combine. At least from the standpoint of monitoring agency practices, the NFLPA has a clear stake in happenings at the combine.

The SI Extra Newsletter Get the best of Sports Illustrated delivered right to your inbox

Subscribe

Second, under federal labor law, collectively bargained rules generally apply to both current and prospective players. This point was at issue in Maurice Clarett’s challenge against the NFL in 2004 over the league’s eligibility rule. This rule prohibits a player from entering the league until he is three years out of high school. I was a member of Clarett’s legal team and we argued, among other things, that the eligibility rule fell outside the scope of NFL-NFLPA bargaining. As we insisted, the rule primarily affects those who, by virtue of the rule, must be outside the NFLPA’s bargaining unit: players not yet in the league. A three-judge panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals disagreed, reasoning that so long as the NFLPA signed off on the eligibility rule, it fell within the purview of the CBA.

Instead of contemplating potential discrimination law and labor law actions, the most effective way to see NFL coaches and scouts stop asking players about their sexual orientation is for those coaches and scouts to start acting like adults.

Michael McCann is a legal analyst and writer for Sports Illustrated. He is also a Massachusetts attorney and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire School of Law. He also created and teaches the Deflategate undergraduate course at UNH, serves as the distinguished visiting Hall of Fame Professor of Law at Mississippi College School of Law and is on the faculty of the Oregon Law Summer Sports Institute.

Michael McCann is a legal analyst and writer for Sports Illustrated and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute (SELI) at the University of New Hampshire School of Law, where he is also a tenured professor of law.