Understanding the NFL's motive to suspend players implicated by Al Jazeera report

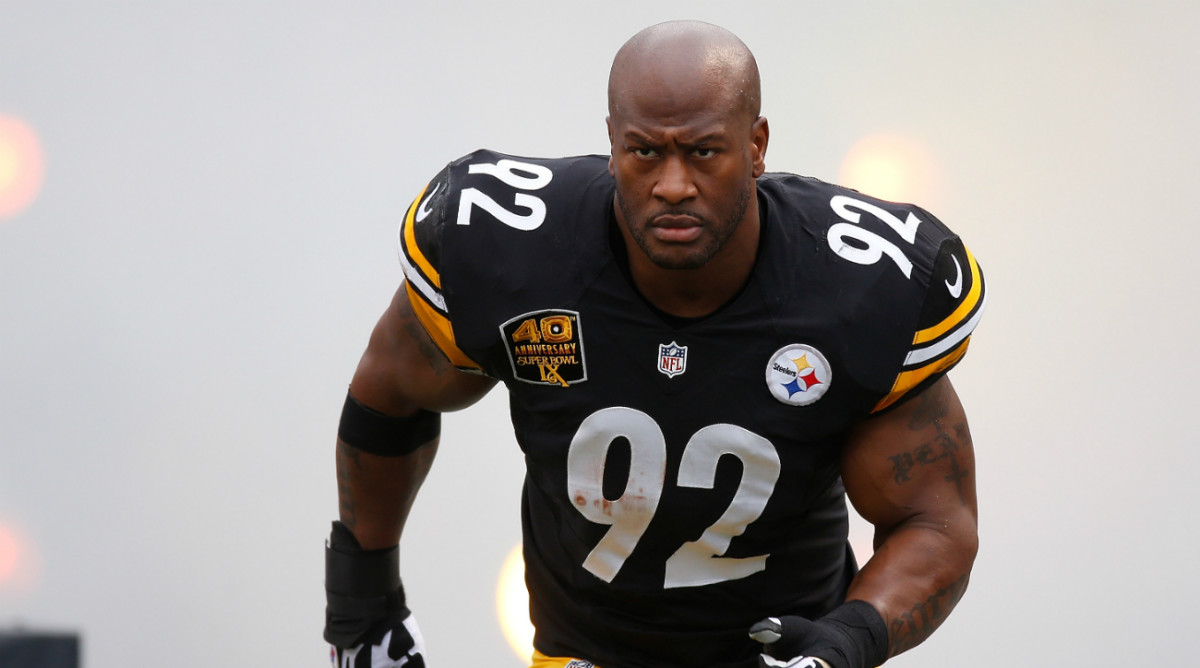

Emboldened by legal victories over Tom Brady and Adrian Peterson, the National Football League on Monday formally threatened four players implicated in the Dec. 29, 2015 Al Jazeera America report, “The Dark Side: Secrets of the Sports Dopers,” with suspensions. In the report, five players—retired Denver Broncos quarterback Peyton Manning, Green Bay Packers linebackers Clay Matthews and Julius Peppers, Pittsburgh Steelers linebacker James Harrison and free agent linebacker Mike Neal—were accused of using substances in contravention of both the law and the collectively bargained Policy on Performance-Enhancing Substances. While the league in July announced that it “found no credible” evidence to support accusations that Manning used Human Growth Hormone, a letter sent by NFL senior vice president of labor policy and league affairs Adolpho Birch to the NFLPA on Monday demands greater cooperation from the other four players. In fact, Birch warns the NFLPA that unless these four players submit to interviews by Aug. 25th, they will face suspensions beginning on Aug. 26th.

NFL threatening to punish players from Al Jazeera PED report

From Birch’s vantage point, the NFLPA has actively stonewalled the league’s investigation into the four players. Birch claims the NFLPA has repeatedly refused interview requests and instead only submitted “cursory” and “wholly devoid of detail” statements on the players’ behalf. Birch also expresses skepticism towards the NFLPA’s pledge that the four statements can be treated as sworn statements—meaning any of the four players could theoretically face perjury charges if their statements contain knowingly untrue assertions. Along those lines, Birch’s letter casts doubt on both the veracity and reliability of the four statements by highlighting that Neal supplied a “demonstrably false” claim or omission in his statement (the NFLPA, per Birch, later corrected Neal’s statement to acknowledge a prior steroid policy violation).

Understanding the NFL’s demands

It is logical why Birch would demand that he interview the four players in person or at least by phone or webcam. In interviews, Birch could much more accurately assess the believability of the players’ denials. Birch, who is an attorney, could ask probing questions and possibly also confront the players with evidence that contradicts or at least complicates their denials. Even if NFLPA attorneys competently represent the players during interviews, the players would still either be forced to answer questions or refuse to answer those questions. The NFL could treat refusals to answer as conduct detrimental to the NFL and thus grounds to suspend.

Birch is also clearly unconvinced by the NFLPA’s assurance that the four written statements may be “treated” as sworn statements. For starters, the league has already identified one apparent error or omission in Neal’s statement. This arguably casts doubt on the trustworthiness and completeness of all of the four statements.

NFL gets as close as it can to clearing Peyton Manning as HGH probe ends

Second, and more significant, a statement treated as a sworn statement is not necessarily an actual sworn statement. If the NFL referred the statements to a prosecutor’s office to investigate for potential perjury charges, the prosecutor could raise doubts about whether the statements are in fact sworn statements.

The NFL was not present when the four statements were made or memorialized into writing, and it is not clear if the players’ statements were duly notarized. These are important distinctions from Brady’s hearing with NFL commissioner Roger Goodell on June 23, 2015 in New York City. During his hearing, Brady gave sworn testimony in the presence of the NFL and in response to questions posed by NFL officials and attorneys.

Understanding the NFLPA’s objections

While Birch has logical reasons to demand interviews with the four players, the NFLPA has its own set of sensible rationales to refuse those interviews. The NFLPA can argue that the league has already cleared Manning, a decision that arguably doubts about the accuracy of Al Jazeera’s portrayal of the four other players. Put more bluntly, the NFLPA might ask, if the NFL could not substantiate a media company’s claims against Manning, why would the league expect to substantiate claims raised by that same media company against other players?

This rationale, however, is vulnerable to counter-arguments. The NFL could insist that it did not technically “clear” Manning but instead found no credible evidence—a narrow but meaningful distinction in that the NFL has not refuted Al Jazeera’s claims, only not corroborated those claims. The NFL could also posit that even if Al Jazeera’s report was wrong about Manning, the company could be right about the other four players and the league has a duty to investigate the claims.

The NFLPA has other reasons to object to player interviews. The NFLPA can maintain that it does not want to unwittingly create a precedent whereby whenever a media company accuses a player of some type of wrongdoing, the player is then subject to an interview with league officials. The NFLPA can insist that such a dynamic would be both disruptive and burdensome, particularly in an era where media companies have substantial financial incentives to levy accusations against athletes.

Cam Newton: Criticism has nothing to do with race

The underlying legal problem: the CBA does not address whether interviews are required

Birch’s letter cites Article 46 of the collective bargaining agreement as well as the NFL Player Contract, which every player must sign in order to obtain eligibility to play in the league. Article 46 accords Goodell with sweeping authority to discipline players for any “conduct detrimental” to the NFL. Goodell has sole discretion to determine whether a player’s conduct is detrimental and whether and how the player should be punished. Similarly, the NFL Player Contract empowers Goodell to punish players for “any” form of misconduct “reasonably judged” by the commissioner.

Notice the intentional expansiveness of these statements. They are broadly worded so as to furnish the commissioner with as limitless discretion as possible. Along those lines, the ambiguously worded “conduct detrimental” standard can include a failure to fully cooperate—again, as determined by Goodell—in a league investigation. Brady, of course, was punished in part for an alleged failure to fully cooperate in the Deflategate investigation when he made his phone unavailable.

Similarly, then New York Jets quarterback Brett Favre was punished in 2010 for a failure to fully cooperate in a league investigation over alleged inappropriate messages and lewd photos (while Brady was suspended four games, Favre was merely fined $50,000). Birch’s letter to the NFLPA on Monday interprets Article 46 and the NFL Player Contract to mean that the four players are legally obligated to “submit to interviews” and “provide meaningful responses to the questions posed.”

Neither Article 46 nor the NFL Player Contract, however, expressly mentions an obligation on the part of players to submit to interviews or answer questions. Although there is a cooperation requirement in the NFL Player Contract, it is—somewhat ironically given that this controversy stems from a media allegation—that the player “will cooperate with the news media, and will participate upon request in reasonable activities to promote the Club and the League.” The cooperation requirement is not expressly mentioned in the context of league investigations.

Roger Goodell's power to discipline stronger than ever after win vs. Adrian Peterson

NFL has the upper hand on law due to the Brady and Peterson decisions

Does the absence of an express requirement in the CBA or NFL Player Contract that players be interviewed by the league mean that players can refuse to be interviewed? Or does the absence of an express protection for players against interviews mean they do, in fact, have to be interviewed upon league request?

Unfortunately for the four players, the Brady and Peterson decisions suggest the latter. In those cases, the U.S. Courts of Appeals for the Second and Eighth Circuit, respectively, determined that the failure of the NFLPA to negotiate express protections for players meant that no such protections existed. As that reasoning applies to this controversy, the failure of the NFLPA to collectively bargain protections for players in regards to league interview requests signals that the players must comply with those requests or face suspensions. Even if the league did not interview Manning, who retired in March, as aggressively as it would interview these four players, the league is not expressly obligated to conduct interviews of players using identical styles and structures.

Further, given the Brady and Peterson decisions, the players would likely find no relief in court. To the extent the NFLPA wants process protections for players, it will need to negotiate with the NFL for those protections.

Michael McCann, SI's legal analyst, is a Massachusetts attorney and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire School of Law.