A Weekend in Buffalo, in the Eye of the Kaepernick Storm

BUFFALO — Before we talk about this city, and football, and effigies, and Tom Brady, Donald Trump and buttocks beer-luges, let’s talk about God.

On Sept. 25, the Episcopal Rev. Will Mebane Jr. stood before the congregation at 128 Pearl Street in the 165-year old red Medina sandstone landmark, wearing not his standard black-and-white vestments but a red No. 7 jersey he’d bought for $100 on NFL.com. Rev. Mebane is one of only a handful of black deans of Episcopalian churches in the United States. The church’s membership is 99% white. The Reverend planned to read a lesson of compassion from the Book of Amos.

“Today’s lessons offer powerful reminders of the pitfalls that await us when we ignore the cries of the oppressed,” Mebane announced in a slow, deliberate rhythm. “It is out of concern for our nation, and frankly, for our souls, that I have chosen to wear this jersey.

“It may be the only way I can get you to think about the killing of unarmed black men and women.”

Mebane, who turned 64 on Sunday, the day the 49ers visited the Bills in Orchard Park, worked various positions for a hospital and a Buffalo TV news station before graduating from Yale Divinity School in 2006. He is tall, mocha-colored and deliberate in all things. Mebane believes Buffalo is leaving behind its African-American population as it makes an economic and cultural comeback, and that the city is one bad police shooting away from erupting into Baltimore or Ferguson.

In a sermon that lasted seventeen minutes and 56 seconds, Mebane described the fear he feels in interactions with police. He crescendoed, voice booming: “God sends prophets like Colin Kaepernick to awaken us! To wake us up before it’s too late. Indifference to the plight of our sister or brother is not acceptable. It is not an option.” In the end, the parishioners broke into applause, the first time, Mebane says, that they’d done so at the conclusion of one of his sermons since he joined the Buffalo church in 2014.

One of the folks not clapping was Sarah Steinmetz, a member of the church leadership who grew up in a military family. Afterwards, she complained about the sermon to friends in the church, who grew concerned she might stop attending as a result of Mebane’s words. He invited her to his second-floor office across the street to talk. For 45 minutes, they discussed nuanced terms like patriotism and idolatry, and the differences therein.

“I still get a little fired up over it,” Steinmetz said on Monday. “Now that I understand why Kaepernick is doing it, I still don’t find it appropriate, but I appreciate what he’s trying to do. Will’s saying the flag should be respected but it shouldn’t be an idol. I still have issues, but fortunately we came to an understanding.”

* * *

There’s something for everybody in the hallowed gravel and dirt parking lots surrounding the building in Orchard Park formerly known as Ralph Wilson Stadium. Men, women and children of all ages and persuasions come here to celebrate the Buffalo Bills, and also to get weird.

You want to see a man light himself on fire? They’ve got that. How about some old-fashioned Tom Brady hate, with a helping of homophobia? That’s just past Gate 2, on Abbott Rd. How about an improvised alcohol luge using only a woman’s naked backside? Yup, right this way. The practice of body-slamming fellow fans through plastic folding tables became so prevalent it was banned in several of the lots closest to the stadium. Yet much of the available parking consists of backyards along Abbott and Big Tree Rd., and owners have traditionally imposed fewer guidelines for those spaces. This is America, after all.

On Sunday, at a tailgate party in a black gravel lot on the north side of the stadium, fans offered passersby opportunities to tackle a dummy dressed in a Kaepernick jersey and afro wig.

As fans streamed through the gravel lot to the stadium, I heard two men in the crowd shout, “Tackle the Muslim!” Why they said that was unclear. It could be due to the unfounded notion that Kaepernick is secretly a Muslim, a rumor borne of his relationship with a female Muslim activist and propagated in conservative media circles and the alt-right.

It’s a tradition in these parts to hang quarterbacks like Brady in effigy, but the arrival of Kaepernick and his national anthem protest left some fans uneasy with traditions. Vendors hawked T-shirts with Kaepernick’s face in the crosshairs of a rifle scope, but two fans who proudly shelled out $10 for the shirts declined to be interviewed or pictured. Said one fan walking by the dummy tacklers: “You’re just making Buffalo look bad!”

The Year of Trump and his no-holds-barred ascension to the brink of our highest office inspired competing groups of Buffalonians to make known their allegiances in the parking lots of Orchard Park. Down the street from the Kaepernick dummy, 38-year-old season ticket holder Chris Sherry and friends played cornhole in the grass behind his camper. Painted on the back of the vehicle in red and blue letters: MAKE BUFFALO GREAT AGAIN. To buttress their statement, the group planted a Trump campaign sign in the grass. One further message, a sticker in the back camper window, read: STOP HORSE ABUSE RIDE YOUR COWGIRL.

I wondered what these fans thought of Kaepernick kneeling during the anthem in protest of police brutality and what he sees as systemic racism. Sherry searched for the appropriate answer. “I don’t want to get all Trump here, but maybe I should,” he said. “There’s the right time and right place to do things… I don’t like this. Ask these guys.”

Sherry’s friend, Greg Becker, jumped in: “We have to understand that not every cop is bad and not every cop is good. In certain situations something bad can happen. To be honest with you, the best way for something not to happen to you is just to follow directions.”

Kaepernick didn’t earn any points among this crowd with his socks depicting police officers as pigs, or his donning of a T-shirt depicting a young Fidel Castro meeting with Malcolm X in 1960.

Another member of the crew, Andrew Heinen, agreed with Kaepernick’s [right to express his] message though not with his method. “The anthem’s a time for us all to come together as a country, so maybe set aside the protest at that time,” Heinen said. “His protest is valid, but I think it's wrong to go about it that way. Putting your fist in the air is better than sitting or kneeling.”

In parking lots west of the stadium, about 60 activists from local organizations Just Resisting (JR) and Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ) clustered among Black Lives Matter banners hanging from beat-up sedans and a planned to kneel outside the stadium at game time, 1 p.m., in solidarity with Kaepernick.

“Critics don’t understand what the offense is with the national anthem, but the national anthem stands for a lot of ugly things,” said Shaketa Redden, a 34-year-old community organizer and graduate of the University at Buffalo. “Black people were still slaves [when it was written]; it was not written for us. And this country still promotes white supremacy.”

Many from this group had also protested in April at a Trump rally in Buffalo, where Bills coach Rex Ryan introduced the eventual Republican presidential nominee. Pressed last week to address the revelation of Trump’s 2005 comments to then-Access Hollywood host Billy Bush in which Trump brags of grabbing the genitals of women without their permission, Ryan said he hadn’t seen the comments and didn’t care to. “I’m under a rock,” he said. “I’m focused on whoever we’re playing, and that’s it.

In addition to supporting Kaepernick, SURJ and JR leaders called on Ryan and several of Buffalo’s Republican elected officials to drop their endorsements of Trump. Said protester James Lopez: “We have one of the most segregated cities in America and a it’s hotbed for Republican leadership that has been very vocal for Trump.”

Added Redden: “Our public figures do not connect with the values we think we should have as a city.”

Numerous studies have listed Buffalo among the most segregated cities in the U.S, and it also has one of the highest rates of poverty among minorities in the nation, according to a 2015 study. These intertwined themes are constantly discussed in regular meetings between Buffalo’s African-American clergy leaders, including Rev. Mebane, and its first African-American mayor, Byron Brown, a Democrat who took office in 2005. The informal meetings began in December 2014, following a grand jury’s decision not to indict the New York City police officer involved in the death of Eric Garner, who famously repeated the words “I can’t breathe” while being placed in a chokehold during his arrest. The phrase became a mantra for the Black Lives Matter movement, which has mobilized protests across the country in the wake of police shootings.

Clergy leaders in Buffalo see in the economic disparity and cultural disconnect a potential powder keg needing only a spark to set it off. “We’re trying to address the social ills here in Buffalo, even in the midst of this incredible renaissance,” Mebane says. “We’ve got to convince the powers that be that everybody ought to rise. The tension in this city is right below the surface. We’re working to make sure it doesn’t explode.”

* * *

When Niners coach Chip Kelly gave Kaepernick the starting nod over Blaine Gabbert early last week, it came as a surprise to some players around the league who’d grown intimately familiar with Kaepernick’s stance through a preseason players-only text group chat discussing the anthem protests.

“By the way he interacted in that group chat you could tell this was his main thing,” said one player who participated in the conversation. “Football has really taken a back seat for him.”

Whether Kaepernick buckled down and demonstrated a recommitment to football following the Week 1 protests across the NFL is a question for the Niners coaches. Of course, the alternative for Kelly was Blaine Gabbert, who was 1-4 in his five starts, averaging 178 passing yards per game, with five touchdowns and six interceptions. Enter Kaepernick, whose first test of 2016 came against a defense that was ranked fifth in the league in points allowed and had given up just two passing touchdowns entering Sunday’s game.

After he was joined by linebacker Eli Harold and safety Eric Reid in taking a knee for the anthem, Kaepernick took his first shot deep downfield on the fifth play from scrimmage and overthrew an open Torrey Smith. It would be a day of trial and error for the sixth-year quarterback, with forced passes, struggles with protection and one big highlight—a 53-yard bomb to Smith, marking Kaepernick’s first touchdown pass in 364 days.

The Niners QB found the going rough against Buffalo’s resurgent defense.

Tom Szczerbowski/Getty Images

He would complete 13 of 29 passes for 187 yards and that one Td, and rush for another 66 yards, earning a tepid endorsement from Kelly as the starter for at least another week.

Watching closely on Sunday was Kaepernick’s former coach at the University of Nevada, Chris Ault, whose pistol-formation concepts were employed by the 49ers when Kaepernick led them to a 12-4 record and an NFC championship in 2013. In a column in August written for the Reno Gazette Journal, Ault supported Kaepernick’s right to champion a cause but decried his choice to sit on the bench during the national anthem as “selfish,” adding, “You never lead by sitting down.”

After the Bills game, the 69-year-old coach offered separate takes on Kaepernick’s performance and his protest. “For a guy that hasn’t had much playing time for three-fourths of a year, I thought he played well enough to create some optimism,” Ault said via text. “Obviously he had some timing issues with a few throws, but I saw him do some good things. As he gets more comfortable with the offense I feel he will be a positive contributor.”

And had Ault changed his mind on the protest? “The only difference,” texted Ault, who’s now coaching in Italy, “is when I wrote that [August column], he was sitting. Now he’s kneeling. We’re halfway there.”

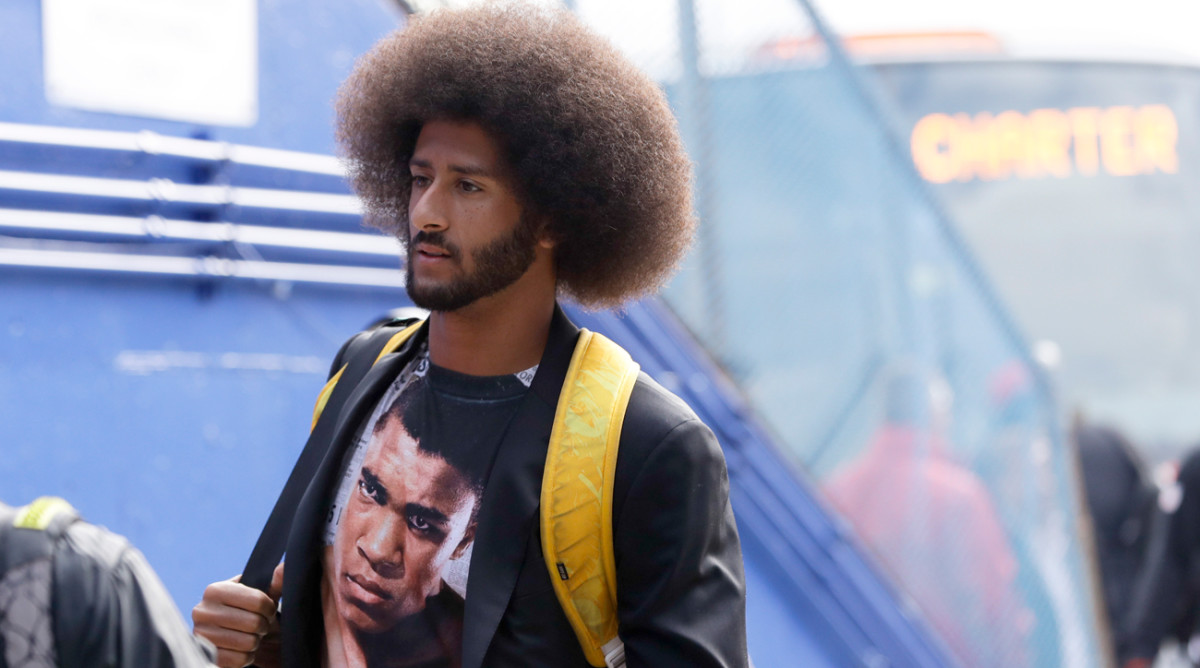

After the game, a decisive 45-16 drubbing that elevated the Bills to 4-2 and dropped San Francisco to 1-5, Kaepernick wore a Muhammad Ali T-shirt to his press conference and spoke at length about his cause, acknowledging the protesters who joined him in sprit at the gates of the stadium.

“Until us as people recognize and address that some of us have privilege, some of us don’t… Some of us are able to do certain things without consequences, and others of us can’t,” he said. “Those are all things that need to be addressed.”

Across the hallway, in the visitors locker room, Bills safety and former Nevada defensive back Duke Williams reflected on the transformation of the player with whom he once shared a college locker room into the man at the center of a national forum on race for football consumers.

“He’s a completely different guy now,” Williams said. “I don’t know what specifically motivated him, but he’s exercising his constitutional rights, and good for him.

“You really have to be politically correct to be a quarterback, but he’s firm in what he believes in, and it takes a lot of courage to do that when it’s so outside the norm.”

Political correctness was on life support on a windy Sunday in Orchard Park, and it promises to remain so wherever Kaepernick goes. His mere presence obliterates the refuge from politics that many find in football and drives debates about patriotism and racism in unorthodox settings. But for some, not even Kaepernick can derail the most basic, core tenets of fandom.

Jeremy Doty, 31 of Hamburg, N.Y., put the issue in terms we can all understand, if not agree upon.

“America has issues, but you still support it. The best example is the Buffalo Bills,” Doty said. “We lose four Super Bowls, but I didn’t turn my back on them. That’s my team, and I stand for them—not like Patriots fans. Ninety nine percent of Patriots fans are not actual fans; they’re just there because of Brady. They’re bandwagon fans.”

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.