Over the span of 72 hours in late July, I had to make one of the most difficult decisions of my life: whether to opt out of the 2020 NFL season. For my first six years in the NFL, I had always balanced my love for medicine and my love for football. But now, with COVID-19 still spreading across the world, my twin passions stood in contrast. On one hand, I had a Super Bowl title to defend; on the other, a global pandemic to deal with.

As both a doc in training and a starter for a championship contender, I remained torn. I had spent nine weeks this spring working in a long-term care facility in Quebec, and being that close to the heroic and ongoing efforts necessary to combat the virus changed my vision of this crisis. During those virtual position meetings with my teammates after shifts spent dispensing medications, drawing blood and caring for elderly patients, I still made plans to play. I even booked my flight and apartment in Missouri in time for camp.

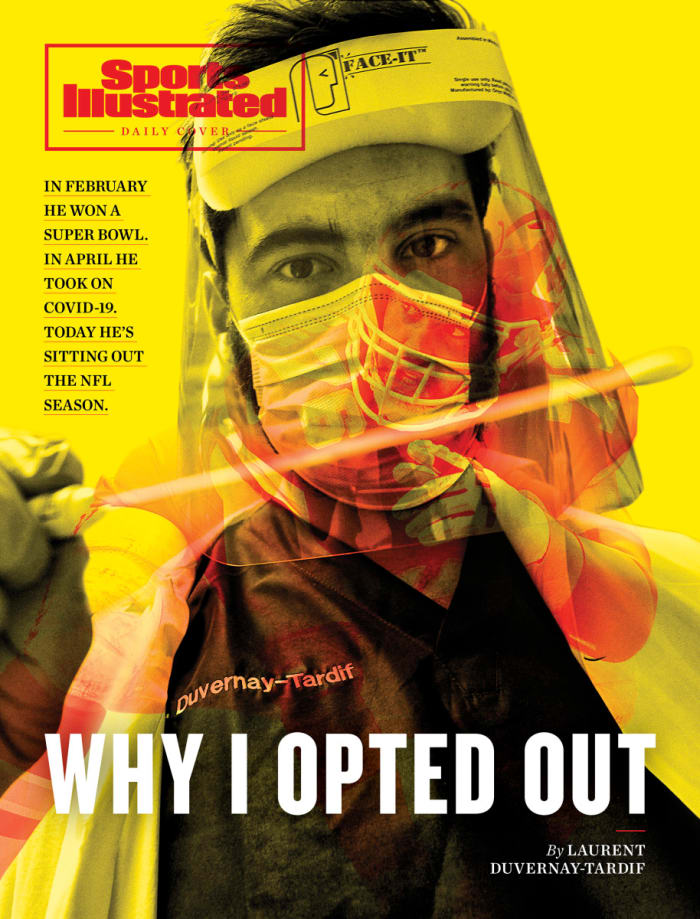

Photo Illustration by SI Art. Photographs by Charles Laberge/Sports Illustrated (portrait); Denny Medley/USA TODAY Sports (reflection)

In an article for Sports Illustrated from April, I wrote that if we were still struggling to contain the virus by the time the season started, we were going to have bigger issues than how to conduct a football season. And here we were, with close to 70,000 new cases a day, just a week before training camp.

I served on the COVID-19 task force for the NFLPA, which alleviated any concerns I had about the protocols that had been put in place to protect the players. Everything from the ramping-up period to how teams will handle their stadiums on game day was reassuring, the right steps. My decision to step away from the game I love for this particular season did not stem from any protocols, or lack of planning, but rather from something that’s more than just about me.

Look, I understand the role that sports play in society. I get the need for games to serve as bonding exercises that rally people together in the worst times. But I had to wonder, in this particular year, did playing follow my larger convictions? Football is, of course, a physical sport that is not without personal risk. But in 2020, just by playing football I could potentially expose cities to COVID-19 and spread the virus. I believe I have a responsibility toward my community from a public-health perspective, and by playing, the risks would become more than just personal, more than simply about me. For my whole career, my two passions had complemented each other and aligned with my convictions. In this particular season, though, they did not align.

The NFL’s approach, understandably, focused on risk mitigation. Nobody in sports can cancel the risks; they’re planning for how to deal with the issues, knowing that they’re present. That puts so much responsibility on the players, who must realize that every interaction they have outside of the club’s facility can potentially put their team and everyone each teammate interacts with at risk.

As soon as I made up my mind, the night before I was supposed to fly to the U.S., I called Coach Reid. I hold so much respect for him and wanted to relay my thought process. That gave the Chiefs as much time as possible to find my replacement. (Kansas City signed veteran guard Kelechi Osemele.)

The Chiefs were incredibly supportive. I saw what Coach Reid and Patrick Mahomes said in their news conferences, how they told the reporters they understood. At that point, I knew I had made the right decision.

Even then, I remember standing on my balcony in Montreal with my girlfriend. “Am I crazy?” I asked. Florence shook her head. No.

“Just remember,” she said, “two months ago you were saying how being in a place like where you were was the toughest thing you’d ever done.”

* * *

I spent nine weeks working part-time at that long-term care facility on the South Shore, about an hour’s drive from Montreal. It was shocking at first, when I approached the job with the mentality of a medical student, trying to optimize my time, traffic in efficiency and see as many patients as possible. My first job was to administer medications in the morning and at lunchtime, one simple task that became infinitely more complicated during the pandemic. Every time I went into a new room, I had to put on new scrubs, a new mask, new gloves and a new visor. And each time I left a room, I had to take all those things off, washing my hands between each step in order to prevent contamination. That process repeated every day for every patient for weeks on end.

The first few days, because I had focused only on the medical tasks in front me, I only saw the negatives, all the steps required and how long it took to take them. After my shifts, I would head to an empty apartment that I owned in Montreal, which I used as a sort of transition zone. I would wash all my equipment, take a shower and change clothes before heading to the other apartment, the home that I share with Florence. At first, I would burst into tears, asking things like, What’s the purpose of all this?

In the beginning, I saw this empty apartment as no more than a sanitary station. But over time, I used it to decompress and reconcile the tedious nature of my new work with its subtle and yet significant importance. I came to realize that the people I met with never left their rooms, or saw their loved ones on anything other than a screen. The nurses, orderlies and caretakers who tended to their needs provided them relief. In most cases, the patients’ interactions with staff members marked their only in-person human contact, and those meetings were made that much more difficult by all the necessary equipment being tugged on and tugged off.

I learned that you have to take the time. That touch matters. And eye contact. And listening, without being rushed. And not acting like a “doctor.” I started using my phone to FaceTime with the family of each patient, and so many relatives burst into tears. Connection, real connection, became part of my job description, more important than drawing blood and putting in urine catheters and crushing up medicine.

I had one patient in a wheelchair who could play online Scrabble using only a stick that she held with her mouth to tap on a mini keyboard. At first, I just gave her medication, but eventually, I started to help her play. She would ask for me when she needed some new word, and I would don each piece of equipment just so I could reinforce that bond, like some sort of scrubbed-out Scrabble coach. It changed my whole approach to medicine, influencing how I’ll be as a doctor in the future.

Especially now, in the time of COVID-19, we tend to collectively focus on the number of new cases, the death rate and the total number of deaths. In doing that, we paint a less-than-complete picture. Where I worked, not many died from the virus. But everyone was impacted by it. Patients died because they were lonely. Many I met with couldn’t eat without assistance, and because of the demands on their nurses, they’d often end up doing lunch at like 2:30 p.m. That’s not a big deal for one meal, but when you eat cold soup day after day after day, it takes a toll.

Conversely, the caretakers were overwhelmed. I knew one couple, one orderly and one nurse, with opposite shifts. The husband (orderly) would work during the day, and then his wife (nurse) would meet him at the hospital, with their six-month-old daughter strapped in a car seat, and he would head in while she would head out. They never saw each other except when they both slept. People like that aren’t part of the equation for how we look at the coronavirus. But the impact on them and their little girl should be.

* * *

Four weeks into my time at the facility, we had an outbreak of COVID-19 cases. We had been in what Canada calls the “green zone,” free of diagnosed cases mostly, but still taking all the necessary precautions. Then my supervisor called on a Sunday night. She was crying, as she tried to figure out how to allocate resources and isolate patients, telling me not to come in. She said about a dozen patients had tested positive.

“You know what?” I responded without hesitation. “I’m coming in.”

The first day I reported for work after the outbreak, the code on the big hospital door was yellow, rather than green. The patients who tested positive were placed into the activity room, as part of a makeshift COVID-19 ward. Employees from different floors no longer mixed.

I don’t want to compare this to a war-time situation, because I’ve never been to war. But it was truly hectic. Thankfully, the staff managed the rash of cases at my facility so well that we were back to the green zone after a few weeks. Their discipline with the sanitary measures and personal sacrifices made for a quick response.

Still, because of not only the outbreak but my time spent on the front line, I came to understand the importance of my coworkers. I held a barbecue for them at the facility, believing I would soon leave for Kansas City and another football season. I told them they were the real heroes. And it’s true. Some of the orderlies and nurses who I worked with have been on the job for three decades. They remain passionate about their work and take pride in connecting with patients. Most of them had to work overtime during the pandemic. All had their vacations canceled.

Like the orderly I knew who stayed an extra 10 minutes with patients to dispense much-needed haircuts. Or the nurses who remained positive, always smiling, never rushed. In a fight as important as the one against COVID-19, these small details matter and more than I ever could have known. We hear so many negatives about the global pandemic. But I found beauty in extreme and adverse conditions that changed my life. My experience taught me that the dignity of patients is sometimes more important than their blood-pressure readings.

Both the patients and the staff stayed positive and resilient, and that’s why I’m going back there to continue to try to help them.

* * *

I put out a statement as the news of who opted out spread across the NFL. I want to be clear here. My goal was never to oppose the Chiefs, the league or my teammates. I’m not trying to convince anyone else that they should sit out this season. I realize my circumstances could not be more unique. I hope that the public realizes that those very circumstances must inform my decision not to play in 2020, that I can’t ignore my life in medicine.

It’s weird to say this, but I miss camp. I’ve been following on Instagram, and every time I see tight end Travis Kelce laughing and cracking jokes, I want to hop on a plane and fly to Kansas City. I miss the guys. I miss the contact. But I also know I made, for me, the right decision.

I want the Chiefs to play all 16 games and make the playoffs; I want my team to repeat as Super Bowl champions, so that when I do return, we’re zoned in on a rare NFL three-peat.

The truth is, if I hadn’t worked in that long-term care facility, I would probably be in Kansas City right now, practicing and grinding though training camp. Instead, this week I’m starting my studies at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard, online. As much as I benefited from my stint in the facility, the time I worked there did not count toward whatever medical discipline I ultimately will practice. I’m targeting classes in health and social behavior at a population level, nutrition from a global population standpoint, biostatistics and epidemiology. And I still plan to work at the long-term care facility.

I’m anxious to see the people I met there, who will never quite know their impact on both me or the wider world. I’m still in contact with my supervisor. All the medical students who pitched in are now headed back to class, increasing the possibility there will be another shortage of personnel. I plan to return as soon as I’m able, because I believe that all my experiences from the Super Bowl to the season I will not play will make me better over time.

What a year, 2020: a title, a pandemic and two life-changing experiences. This stretch will remain one that I will not soon forget. In the meantime, I hope the Chiefs smash the Texans on Thursday night.