Business of Football: Creative Clowney Trade Squashed; Running Backs Paid

There are a couple of flashpoint moments on the NFL calendar when player contract activity surges: late February/early March, before the start of free agency; and late August/early September, before the start of the season. The time we just witnessed the last two weeks is when the front office delivers the team to the coaches, when “me time” of individual negotiations turns to “we time” on the field.

Despite the uncertainty of playing through a pandemic and the reality of a diminished 2021 salary cap, business was booming in the days before the 2020 season. After a quiet offseason with only a handful of player contract extensions, it almost seemed as if teams and agents looked at each other and said: “Well I guess we’re doing this!” and got down to business.

Amid a flurry of activity over the last couple of weeks, here’s what caught my eye …

A moneybag trade! Or not

I was downright giddy in 2017 when the Browns acquired Brock Osweiler and his albatross of a contract ($16 million guaranteed)—with no intention of playing him—to also acquire a second-round pick from the Texans. It was a new way of doing business in the NFL, one popular in the NBA: A team takes on a “bad contract” in exchange for a future asset. I thought they had started a trend that would allow general managers and front offices to separate themselves from their peers when it comes to player acquisition and asset allocation. But alas, there have been no similar moves since. Until one almost happened last week.

Reports indicated that the cap-challenged Saints (and the cap-challenged Ravens) had agreed to send a draft pick to another team to acquire free agent Jadeveon Clowney. The Saints would have made that deal with the Browns and the Ravens with the Jaguars, per those reports. Here’s how it would have worked: One team would have signed Clowney to a one-year, $15 million contract, then paid him a $5 million bonus before trading him away for a second-round pick. Everyone would be happy with this creative plan, right? Wrong, as the NFL Management Council reportedly nixed the scheme, leaving Clowney to sign with the Titans, in a traditional deal with no other team involved.

When I worked for the Packers, I experienced the league’s distaste for this type of move firsthand. There, under the direction of general manager Ron Wolf, we drew up a couple of proposals to allow teams to trade cap room and cash (up to a $5 million limit) for players. The deals would have helped talent-starved teams with a surplus of cap room as well as cap-challenged teams craving flexibility in roster management.

The negative response from the NFL Management Council was something like: “You make your bed, you sleep in it.” In other words, the league was not going to allow teams that were undisciplined in cap management—in the Clowney case, the Saints or Ravens—to “get bailed out.”

I suppose the difference between the Osweiler and Clowney situations was that Osweiler was under contract and Clowney was a free agent. The premise of the trade, however, was the same: trading a financial burden for a future asset. Although this one was disallowed, my hope is there is more creativity and disruption in player movement; it would not only spur “buzz” but let front offices and general managers separate themselves from their peers.

Watson vs. Mahomes: Loses on the field, wins off

The Texans extended quarterback Deshaun Watson’s contract last week, an easy and obvious decision for the face of the franchise who has impressed with his humility and scintillating play. When your team’s best player is also your team’s best person, that is gold.

Although Watson’s team lost to the Chiefs on Thursday night, his contract appears to be a win over that of the Chiefs’ Patrick Mahomes. I wrote at the time about the deficiencies of that contract, especially about its length and early money, the latter of which is shown in this comparison:

Mahomes: $10 million signing bonus, $63 three-year amount, $141 five-year amount

Watson: $25 million signing bonus, $75 three-year amount, $144 five-year amount

Watson also retains “optionality” on his future finances, as he will likely negotiate at least two more contracts during the length of the Mahomes deal.

This offseason featured many quarterback contracts, including one-year deals for Dak Prescott and Philip Rivers and a two-year deal for Tom Brady. Beyond those shorter deals, here is a three-year cash scoreboard in 2020–22 earnings:

• Kirk Cousins: $96 million

• Ryan Tannehill: $91million

• Watson: $75 million

• Mahomes: $63 million

• Teddy Bridgewater: $63 million

Ramsey, Hopkins turn the tables

In the past year, the Rams and Cardinals made blockbuster trades to land top-tier talents Jalen Ramsey and DeAndre Hopkins from the Jaguars and Texans, respectively. The acquiring teams, however, did not complete contract extensions at the time of the trades, allowing the players to wrangle two of the most player-friendly contracts in NFL history.

At the time of the trade last year, Ramsey was engaging in a “hold-in”—being present with the team but putting forth little effort—to engineer his way out of Jacksonville. And while Hopkins’s issues with the Texans were less public, he was clearly elated to go to the Cardinals. Were contract extensions made “part of the deal,” it was highly unlikely Ramsey and Hopkins would have balked. But no deals were done until last week, when the Rams and Cardinals were squeezed by their player negotiations.

Ramsey set new standards in all categories for the defensive back market. And Hopkins, despite having three years left on the contract acquired from the Texans, negotiated an astonishing $54 million guarantee with all kinds of bells and whistles—player voids, no-trade clause, no tag clause, etc.—all without the use of a traditional agent.

The Rams and Cardinals had leverage to forge team-friendly extensions at the time of acquisition, but once that time passed, the leverage shifted to the players, who negotiated decided “wins” over their new teams.

Running backs delight

I often say I feel for running backs. They are the NFL’s most disadvantaged group financially, with primary earning years being unpaid (in college) or low-paid (on a rookie contract). And for several years there was a wasteland of running back contracts, with no one other than LeVeon Bell making more than $7 million per year.

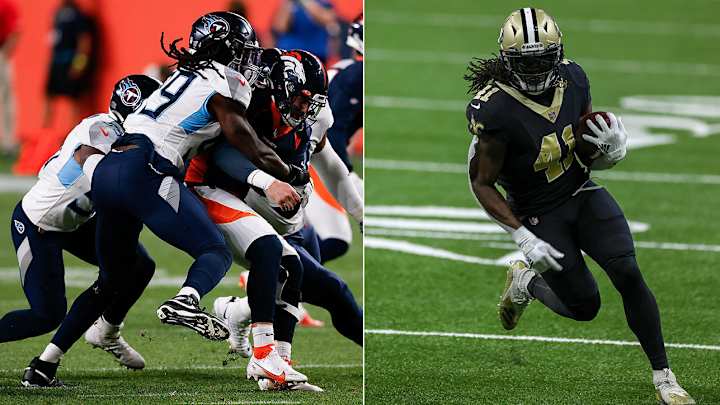

That began to change last year with the Ezekiel Elliott extension and this year with Christian McCaffrey. And it accelerated in recent weeks with new deals for Derrick Henry, Joe Mixon, Dalvin Cook and Alvin Kamara. It was a market reset at the position that needed it the most.

As to what you need to know about the four recently completed contracts (Henry, Mixon, Cook and Kamara)? It’s that they can all be described like this: two years, $25 million to 28 million, and then “we’ll see.”

Competitively balanced noise

After my last column wondering why commissioner Roger Goodell would not step in and mandate competitive balance in terms of fan attendance, he doubled down in a CNBC interview and reiterated that he did not see problem with competitive balance. Well, in the words of George Constanza: “It’s not a lie … if you believe it.”

Meanwhile, the NFL had sound engineers create “soundtracks” for each team, a Spotify playlist if you will. Now in stadiums with no fans, “league-curated audio” is being pumped into empty stadiums.

League-Curated Audio is now the name for one of my fantasy teams.

Booing not part of the plan

Finally, speaking of crowd noise, things did not go as planned with one of the two stadiums where there were fans in Week 1, Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City. As the teams gathered in a show of unity, the crowd booed, all the while performing the racist tomahawk chop.

After a volatile offseason revolving around discussion of peaceful player protest, unity and equality, it was an unfortunate scene, and one that even the NFL could not edit out of the broadcast. With everything the NFL and its players had worked on the past several months, it was clear that some fans—many of whom just want the players to “stick to sports”—were not part of that plan.

In a curious way, maybe it is better that many stadiums have no fans right now.

Andrew Brandt is the executive director of the Moorad Center for the Study of Sports Law at Villanova University and a contributing writer at Sports Illustrated. He has written a "Business of Football" column for SI since 2013. Brandt also hosts a "The Business of Sports" podcast and publishes a weekly newsletter, "The Sunday Seven." After graduating from Stanford University and Georgetown Law School, he worked as a player-agent, representing NFL players such as Boomer Esiason, Matt Hasselbeck and Ricky Williams. In 1991, he became the first general manager of the World League's Barcelona Dragons. He later joined the Green Bay Packers, where he served as vice president and general counsel from 1999 to 2008, negotiating all player contracts and directing the team's football administration. He worked as a consultant with the Philadelphia Eagles and also has served as an NFL business analyst for ESPN.