Editors’ note: This story contains accounts of sexual assault. If you or someone you know is a survivor of sexual assault and is seeking help, contact the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 1-800-656-4673 or at https://www.rainn.org

The protest was supposed to kick off at 1 p.m. on a Sunday, not unlike most Browns home games. And while its organizer didn’t expect anything close to a full stadium’s worth of supporters outside the team’s practice facility in Berea, Ohio, the 17,000 views on his Reddit planning thread had left him hopeful about the turnout as he steered onto Lou Groza Boulevard that afternoon wearing a Browns jersey and toting a handwritten poster that read NO WATSON IN CLEVELAND.

For Raymond Braun, decades of commitment had led to this expression of disgust. A Browns fan from birth, he was raised on stories about his late grandfather drinking beer with Otto Graham and Lou the Toe, and about his dad celebrating the team’s last championship, in 1964. Now 44, Raymond typically treks in from Cleveland Heights for the live experience once or twice each season, though he prefers to host his own watch parties. “I’d never miss a game,” says Braun, a network engineer who counts among his most prized possessions a ’60s-era Browns-orange knit hat that has his grandad’s name and address sewn onto the interior.

Then, on March 18, the Browns sent a haul of draft picks to the Texans in exchange for quarterback Deshaun Watson, who at the time faced (and still faces) 22 civil lawsuits filed by massage therapists, each accusing him of sexual misconduct. After news broke of a corresponding contract extension that guarantees Watson an NFL-record $230 million, Braun scrolled through social media and found “so many people” defending the move by citing two different Texas grand juries that had declined to indict the 25-year-old on criminal charges. (In his introductory press conference, Watson said he had “never done these things people are alleging” and did not plan to seek counseling because “I don’t have a problem.”) But Braun also read numerous articles detailing the allegations against Watson, including a Sports Illustrated report about one woman, not among those suing, who recalled a similarly problematic encounter with the QB. “It’s one thing if one person accuses,” Braun says. “He’s almost got as many accusers as he does years on this planet. At that point, I was very against [the trade].”

Braun was looking for a way to vocalize this frustration when he came across a Reddit post—“Call to arms for Browns fans”—that proposed staging a demonstration against the trade. And so he leapt to help, starting his own thread, alerting Berea city officials about a gathering and spreading the word in his social circles. The plan: “Let’s do everything we can to stop this,” Braun remembers thinking, “or at least yell as loud as we can until they can’t avoid us.”

What only a select few people in his life knew at the time, though, was the deeply personal motive he had for speaking out in the first place. Says Braun: “I am a rape survivor.”

The incident occurred when Braun was 36, he says. He prefers not to get into specifics, but he adds that it wasn’t his first traumatic sexual experience. At 17, Braun recalls, he fled an attempted rape by jumping out of a car, vaulting over a fence and sprinting home. In his 20s, he was attacked by an ex-boyfriend. That time he defended himself long enough to dial 911 before his ex ripped the phone out of the wall. “You could break your leg, and it’s going to heal,” Braun says. But these assaults are “not the kind of thing that heals. It gets easier. It doesn’t get better.”

Years later, as Braun processed the accusations against the new face of his favorite franchise, he was “triggered right away.” Initially he found himself outraged at Browns management, which had cited “extensive” research into Watson’s character before the trade. “What are they sending as a message?” Braun asks. “In the smoke-filled back room, they said, ‘People will be upset—and we’ll win some games, and people will get over it.’ ” (Watson, meanwhile, remains under investigation by the NFL for violating its personal conduct policy. He could still face suspension.)

Disappointment followed, then, when Braun pulled up to the Browns’ practice facility to find just a handful of police and journalists—and zero marchers. Still, he summoned the courage to stay for an hour, twice climbing from his car to take a brief, solitary stroll along the fence that surrounds the complex (though he left his sign behind). And he ultimately drove home confident that his efforts were not in vain, having spoken outside to an Akron Beacon Journal reporter for an article about fed-up fans. “Whether a thousand people showed up or not,” Braun says, “the Browns knew there was a protest.”

As time passed, Braun would feel empowered, too, to make himself heard in another way. He would tell the full extent of his story—not in protest, but to shine a light on all sexual assault survivors, in Browns nation and beyond.

To let them know: They are not alone.

Raymond Braun is not alone.

In the two weeks following Watson’s acquisition, the U.S.’s largest anti-sexual-violence organization, RAINN, saw a 23% increase in calls to its sexual assault hotline, according to president and founder Scott Berkowitz. “Not everyone mentions the story [when they call],” says Berkowitz. “But it’s clear that it’s stirred up a lot of emotions and a lot of anger.”

Such an “immediate effect on hotline usage,” Berkowitz continues, aligns with the response RAINN saw to other prominent cases involving public figures accused of sexual assault. (As a past example he cites Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing.) “In general, half or more of the folks are calling soon after [being assaulted].” Berkowitz says. “People who are calling days or weeks or years later—those are the kinds that we typically see an uptick in related to news stories.”

Why? Remember: “Trauma is something that doesn’t just go away,” says Berkowitz. “So when there’s an event that reminds them of something related to their own assault, it can make the memories fresh. Even people who experienced rape many years ago, and have continued working and living their lives, seeing or reading [about] something like this can be really painful. They’re looking for someone who doesn’t blame them, but who is a friendly voice—who can help figure out how to keep going.”

That response has been even starker at the local level, where the Cleveland Rape Crisis Center received 106 calls to its own hotline on the Saturday and Sunday after the Watson trade, a 152% increase from a typical weekend. This included 69 contacts on the day of Braun’s protest, a 138% increase from its average daily total in 2022. Even three weeks later, calls were still nearly 30% higher than they were before the trade. Says Sarah Trimble, the center’s chief external affairs officer: “It was very triggering to survivors in our community.”

As with RAINN, some CRCC callers asked about the nonprofit’s array of free programs for survivors, such as trauma-informed counseling and help navigating the judicial system. But in both cases, people mostly “just needed to talk,” Trimble says. “They felt like they’re not a priority, and winning football games matters more than the people in our community who have experienced sexual assault.”

People like Marla Ridenour.

A Beacon Journal sportswriter who has covered the Browns for various Ohio outlets as far back as the 1980s, Ridenour identified herself as a rape survivor in a March 26 column headlined BROWNS’ DESHAUN WATSON TRADE TRIGGERS PAST FOR SEXUAL ASSAULT VICTIMS. I AM ONE OF THEM. Ridenour, 67, laid out how her experience, which occurred in the mid ’70s, when she was in college, still affected her nearly five decades later. “I cried myself to sleep … when news broke that the Browns were flying to Houston to meet with Watson,” she wrote. “Like so many women who are victims of sex crimes, I know what it’s like not to be believed.”

Ridenour recalls wrestling for “two or three days” over whether she would share that story with readers. “I didn’t know if I’d have the nerve,” she says. But she forged ahead, seeking “catharsis after keeping a 47-year-old secret.” And indeed she felt freed when she sat down to type; the words poured right out of her. What she didn’t anticipate, though, was the outpouring of support that followed. “The response has certainly convinced me that I did the right thing.”

More than 200 related emails currently populate Ridenour’s inbox—“some are from victims, some are from Browns fans, some are both,” she says. “A lot of them are confessing to me the details of what happened to them. Some are so gut-wrenching.” Other people have written letters—one was about a family member who’d taken their life after an assault—or even approached Ridenour at work, at a Cavaliers game.

She estimates that 60% of the people who reach out “know someone, or had it happen to them. The other 40% are people thanking me for sharing this.”

Ridenour is hopeful that her column will help chip away at a culture of silence. “Every day that goes by, I get more emails or texts or Twitter messages,” she says. “It’s kind of staggering how pervasive this is, and how so many people carry this with them and don’t talk about it.” She recounts how a high school journalism teacher in North Carolina reached out to say that he was planning to assign his students to read her column, and how another person wrote about sitting down with their teenager “to talk about these kinds of things.”

“I didn’t feel like I could tell my parents [at the time of the assault],” says Ridenour. “I do feel like an unintended [consequence of the column] might be to open up the conversation.”

Braun, too, was initially torn about the idea of speaking out as a survivor, especially as a white man. “I always try to check my privilege, and know when I need to be listening and not talking,” he says. He remembers thinking: “This is a believe women thing.” But ultimately he was convinced to use his voice by one of the few people in his life who knew his story.

In 2017, Alisa Alfaro was sexually assaulted by a Cleveland Heights neighbor who entered her house while she was sleeping, using a key she’d given him to walk her dogs. The man was eventually sentenced to 16 years in prison, but not before Alfaro suffered the added humiliation of what she describes as skepticism when she reported the incident to authorities who didn’t believe her.

Alfaro, 53, considers herself a casual “hometown fan,” far from a Cleveland diehard. But she has watched closely how the Watson trade has been received among her more passionate friends, ranging from “disgusted” to “curious how it all plays out.” “The male side,” she observes, “wants to bring up the fact that [grand juries] failed to indict him twice. But that doesn’t mean they found him innocent.” And women, Alfaro says, “are very concerned about the image that [this situation] is giving the Browns.”

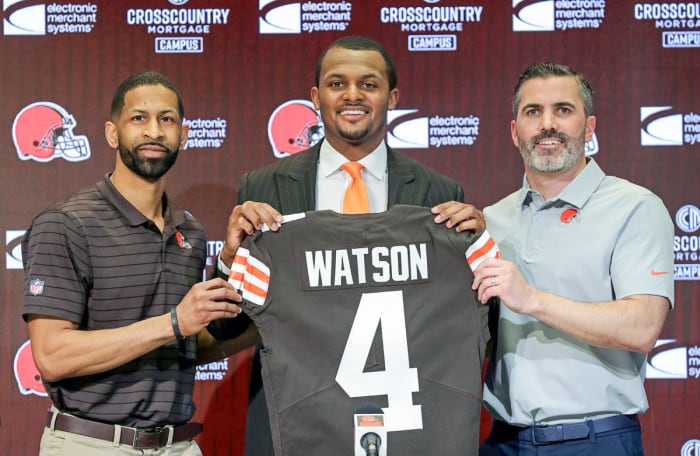

Watson, with coach Kevin Stefanski (right) and general manager Andrew Berry.

Jeff Lange/USA Today Network

Beyond football and fandom, Alfaro is more concerned with how the arrival of Watson reinforces existing power structures around sexual assault. “All of the doubt, the victim-blaming, it’s why we don’t report,” she says. “It’s why [survivors] can’t come forward and be taken seriously. Those of us who can, must.”

That, in essence, is what she told Braun when he expressed reservations about coming forward. “She reminded me that this is not just about believing 22 women; it’s about believing everyone,” says Braun. “As an LGBT male … I realized they need a voice as well.”

The impact isn’t limited to survivors themselves, though. Says Trimble: “No experience can match that of the person who experienced rape or sexual abuse. [But] I think these headlines do retraumatize the secondary survivors as well—parents, family members, partners, other folks in the blast radius. And we’ve certainly seen that in the community.”

LaShawn Terrell is one of those community members. A Cleveland sports fan for all of her 49 years, she counts several sexual assault survivors as close friends. And when she first heard about the Browns’ pursuit of Watson, she immediately thought about the women accusing him. “I was numb,” Terrell says. “I didn’t know how to feel. Your heart bleeds.”

So Terrell tweeted to her 1,200-odd followers to "consider supporting the Cleveland Rape Crisis Center with volunteerism and donations,” and she shared a screenshot of her own financial gift. Two days later—just before the Watson trade—she received an email from the organization, thanking her for 25 additional donations that had followed her tweet. But that was just the beginning.

Over the next month the CRCC received contributions from 2,300-plus donors, totaling close to $125,000, an unprecedented flood for the 48-year-old organization. “The #MeToo movement in 2017, that was in the headlines for weeks,” says Trimble. “And while we experienced a substantial increase in calls to our hotline, it did not manifest in the same way that it did here.”

About a third of those 2,300 donations were made for exactly $22, a show of support for the 22 women suing Watson. Similarly, a third of the donors explicitly cited the Browns and/or Watson as their motivation for giving. Fifty or so people marked their contributions in honor of Baker Mayfield, the quarterback Watson is replacing. Braun gave $50 twice—once in co-owner Dee Haslam’s name. Carly Teller, the wife of All-Pro Browns guard Wyatt Teller, tweeted a screenshot of her donation from her then-public account, writing to Terrell, “Thank you for raising awareness!”

Others expressed their displeasure over the move by taking aim at the team that made it. NFL Network podcaster Marc Sessler and sportswriter Joe Posnanski each publicly renounced their Browns fandom. Andrea Thome, the wife of baseball Hall of Famer Jim Thome, who played for 13 years in Cleveland, tweeted that after “40 years as a fan” she had canceled her family’s four season tickets. “This is my line in the sand,” she wrote, later adding that she’d diverted the money instead toward organizations that support victims of domestic violence and sexual assault. And Michael Brennan, the mayor of University Heights, 20 minutes east of FirstEnergy Stadium, posted on Facebook about how he had boxed up decades’ worth of jackets, jerseys, hats, pennants, mini helmets and footballs, and banished all of his memorabilia to the basement.

“I watched a lot of bad football for a lot of years and stuck with this team, but I feel like the Deshaun Watson trade is a bridge too far,” says Brennan, who says he’ll shift allegiances to either the Bengals or the Bills. “Sports are supposed to be an escape. When this is right in front of you, how can you enjoy it?”

Raymond Braun senses his enthusiasm waning, too. Ordinarily, around this time of year, he would be devouring draft and OTAs content; now, the emotional impact of the Watson news has him barely scanning headlines. He isn’t quite prepared to stash away his granddad’s knit hat, and he doesn’t plan on adopting a new team just yet. But he’s also not sure how many Browns games he’ll be able to stomach watching this season if Watson is under center.

“I just don’t know how I’m going to feel,” Braun says with a sigh.

Remember: It gets easier, not better.

Read more SI Daily Cover stories:

• Inside Hue Jackson’s Tanking Allegations Against the Browns

• Behind the Spectacle of Kaepernick’s Comeback Tour

• The Return and Rebirth of AD