Vann McElroy’s Hometown of Uvalde and How He’s Coming to Grips with Tragedy

In this story:

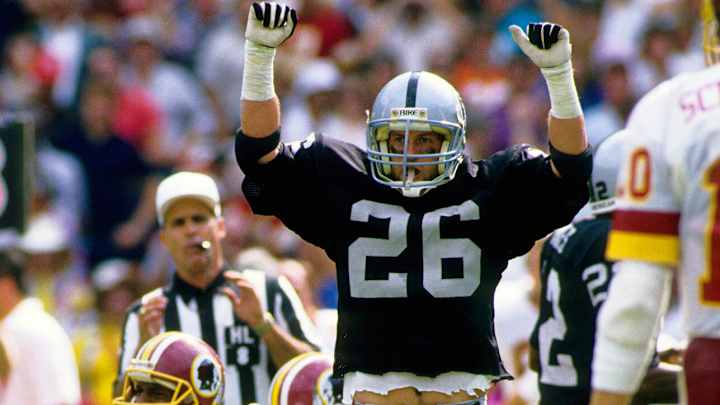

Vann McElroy doesn’t pass by Robb Elementary every day, but he lives close enough to where a simple drive anywhere into town can take him past the school. And that’s the very circumstance the former NFL safety—an All-Pro four times and a Super Bowl champion for the Raiders in the ’80s—found himself in the morning of May 24.

“It’s bizarre, but I decided to go over and eat at Vasquez. I don’t even know why. I was just by myself, and they have the greatest enchiladas on the planet,” he says. “So I take off and I always go the back way when I’m headed that direction. And I always go by Robb when I’m going over there. As I was driving through, I began to notice the exits that would be going in and out of the school. There were starting to be lines of cars, and then I began to notice police cars and the lights flashing.

“And then behind me on both sides, you saw policemen, highway patrolmen; they all had their lights on, just flying in from every road you can imagine. I had no clue what was going on at the time. I’m just going, Goodness gracious.”

McElroy drove around a little more. The traffic was swelling. And once it stopped, he spotted a couple on the sidewalk and asked them what was causing the commotion.

There’s just been a shooting at the school, they said.

The seriousness of the situation hadn’t even sunk in when McElroy looked around and saw more cruisers from the police, border patrol, sheriff's office and highway department. He pulled over and furiously started to send texts, trying to make sure his family and friends were O.K., including his 8-year-old grandson, William Vann McElroy III, a second-grader at Anthon Elementary across town.

“Anthon is just a little ways away from Robb; it’s not far at all,” McElroy says. “It could have just as easily been that school.”

On May 24, McElroy wasn’t the local football hero who’d started a successful sports agency out of the ranch he and his wife built on the outskirts of town. He was just Vann from Uvalde, Texas, another stunned citizen with deep, lasting ties to a hometown that would never be the same, doing his best to come to grips with what was happening in his backyard.

McElroy says to understand what people in Uvalde are going through, you have to first understand the town he’s from, a South Texas community of about 15,000 people some 83 miles West of San Antonio. He and his parents first moved to Uvalde, from Alabama, when he was 6 months old, and he attended Dalton Elementary before going to the junior high and then Uvalde High School, where he became a star.

“I grew up on Laurel Street, and I have to tell you, Laurel—the neighborhood there where I grew up—had to be the all-time greatest neighborhood of neighborhoods in the world,” he says. “It was kids everywhere. Everybody goes to church here and then on Sunday afternoons, everybody would go eat lunch and we would gather together at what’s called Little Park, in that little area over there and we’d all be Roger Staubach, or somebody on the old Cowboys or different teams, and we’d go play football.

“Don McLaughlin, who’s the mayor, he lived in that neighborhood, the alley over from me.”

McElroy then told the story of a minibike that McLaughlin got when he was a kid and how the future mayor was driving around one day, and asked McElroy whether he wanted to give it a try. He answered yes, then drove it into a fence, leaving the bike in pieces.

“Those are the types of stories, as a child, that I have from growing up in Uvalde,” he says. “It’s a place where everyone knows everybody. You know everybody.”

And maybe, for McElroy himself, that’s proved best by his connection to the one Uvalde native who became more noteworthy than he did—an actor 10 years his junior, Matthew McConaughey.

“When I was 9 years old, his dad was a coach of the Rotary Indian Little League team, and he had the draft in their backyard,” McElroy says. “He drafted me. So [McConaughey’s] dad was my Little League baseball coach, as crazy as that sounds.”

Those connections are why, when McElroy’s pro career was winding down, and he and his wife, Gale, were living in Southern California, that tug of Uvalde pulled him back.

They wound up buying a 150-acre ranch five miles outside of town in 1990 and built their dream home. McElroy was traded that fall from the Raiders to the Seahawks, playing two more seasons in Seattle, giving him 11 in the NFL. He then wound up getting into player representation and started his own agency, in part because it would allow him to raise his family in the town he grew up.

All four of he and Gale’s kids went through the Uvalde school system (none attended Robb), and even with all of them grown and out of the house now, the community McElroy grew up in is intact in a lot of ways—to the people he’ll run into at the H.E.B. (branch of a supermarket chain) or Walmart on a daily basis that he’s known for decades.

“I don’t lock my doors,” he says. “It’s still that type of community. Everyone’s looking out for the other one’s kids. It’s just a good place that way.”

Which is why he and so many others are so deeply affected by what happened last week.

In the days after the tragedy, McElroy did what anyone would, trying to figure out whether there was anyone he knew that was directly affected. He knew some grandparents and others who had kids that attended Robb but survived the attack. Then he struggled to process it. Nine days later, it still seems impossible.

“It’s a complete shock, everyone is just devastated, and I think everyone is dealing with it in their own way,” McElroy says. “My oldest son, V.J., and his wife, Margo, they have three kids, and they were struggling. They were emotional at times, and they’ll still break down a little bit, obviously hurting for the parents that lost their children, but knowing you could be one of those parents.

“It’s an emotional time for everyone trying to process everything, and not only what took place, but what you do going forward, how’s all this gonna work, in trying to get out of the fog of not wanting to …”

McElroy then stopped, almost acknowledging there really isn’t a road map for anyone.

“You find people don’t really want to do anything,” he says. “You’re just kind of in such a fog, and such shock. That’s where everyone’s at mentally, trying to process this deal. And, still, I think, not believing it can actually happen here.”

But it did. And the next step will be doing something about it. While McElroy was coy on where that step will take him—he’s working on something significant to try to make a difference, and there will be an announcement soon—there’s no question among those in town that this is a time to band together. If you notice that it may seem like they’re closing ranks, there’s a reason for that.

“I look at Uvalde as a family, so you just look at your own family, you get into situations and there are families where it might divide them even more, with everyone having a different agenda,” McElroy says. “Everyone’s got their own thing going on, and that can create a very divisive atmosphere and environment. And the thing I’ve noticed in this great community is everyone’s coming together. You see people hugging each other and loving each other.

“And what those outward signals and signs tell me is that people are wanting to help and make things right.”

That doesn’t, by the way, mean those on the outside aren’t doing their part. As McElroy and I talked, Hall of Fame Raiders coach Tom Flores was calling, just the latest in a line of his teammates and coaches to call, including Howie Long, Terry Robiskie and Matt Millen. Baylor teammates and coaches have called, too, all asking what they can do to help. “It’s been overwhelming,” McElroy says.

And, really, what he’s asking for is to see Uvalde heal and get back to being the kind of place you could set your watch to, as impossible as that sounds right now. It’s still a place that’s had the same guy, James Volz, writing about local sports for the Leader News for what McElroy calls “eternity.” It is still a place where McElroy will get out on Friday nights to games. “I don’t go to every game, but we go, and we still support the Coyotes,” he says, “Coyotes” rolling off his tongue like Bud Kilmer said it in Varsity Blues.

The best way to get there, he thinks, is to make schools safer and more secure, and he has ideas for it, too (though he didn’t want to get into any politically charged areas during our conversation). If that happens across the country, then even better.

“If the country would set out on an initiative to make every school completely safe, which you can,” he says, “I think you begin to really create a memory for these kids.”

For now, though, just having that happen in Uvalde would be a nice start, and maybe create a path back to being the kind of place where McElroy never felt the need to lock his door.

McElroy retired from his sports agency about a year ago and had settled into a simple life in Uvalde, his kids all relatively close by, with lots of friends down the road. He’s active in his church. People in town still pepper him with football questions when they see him, but he says, “I’m a bit worthless and uninformed now. It’s a good place to be.”

Until last week, it really was what he wanted to slow down to, at 62. Life back home.

“Gale and I have enjoyed our time. We travel here and there and do some things,” he says. “Brother, I have been blessed way more than I deserve coming from a very poor background. My parents never owned a home.”

And therein lies another strong connection to the town for him and Gale. When he was drafted by the Raiders in 1982, he took his first check and bought the house on Laurel for his parents. He still owns it—“it’s a hard one to give up.”

But more than any possession, it’s the people in town that have kept him here. He loves the area’s sizable Latino community (“Their culture is wonderful”) and has old teammates from football, and the baseball team he won a state championship with as a high school junior. Others have moved in, he says, from New York and California, looking for a small town such as his, and have assimilated nicely.

All now are looking for answers that won’t come easy.

The 19 children and two teachers who had their lives taken away aren’t coming back.

“It’s largely still full of people that were raised here, their families, their grandchildren. They’re still here,” McElroy says. “And like I said, I go into town, I’m gonna be ready to shake a few hands and talk about a few old stories, and have fun and love on people’s kids, and just have hope for them. And I know the community, people out there, we just would ask, the biggest thing right now, just, goodness gracious, because it’s impossible, just keep everybody in your prayers, man.

“It’s a devastated community that’s just trying to figure it out. I don’t know when that will totally happen. I know the toughest part of this process, and I mean this in the best way I know how to say it, it’s an important thing. You know the healing has begun when you’re able to forgive the one that committed these horrible acts. And that will come differently for everyone. But I think that’s the end result.”

Which is McElroy’s way of saying after the news crews pack up and the spotlight has dimmed, his hometown will still have a long way to go.

More NFL Coverage:

Albert Breer is a senior writer covering the NFL for Sports Illustrated, delivering the biggest stories and breaking news from across the league. He has been on the NFL beat since 2005 and joined SI in 2016. Breer began his career covering the New England Patriots for the MetroWest Daily News and the Boston Herald from 2005 to '07, then covered the Dallas Cowboys for the Dallas Morning News from 2007 to '08. He worked for The Sporting News from 2008 to '09 before returning to Massachusetts as The Boston Globe's national NFL writer in 2009. From 2010 to 2016, Breer served as a national reporter for NFL Network. In addition to his work at Sports Illustrated, Breer regularly appears on NBC Sports Boston, 98.5 The Sports Hub in Boston, FS1 with Colin Cowherd, The Rich Eisen Show and The Dan Patrick Show. A 2002 graduate of Ohio State, Breer lives near Boston with his wife, a cardiac ICU nurse at Boston Children's Hospital, and their three children.

Follow AlbertBreer