Primed for Rio, Katie Ledecky thriving in high-pressure Olympic atmosphere

RIO DE JANEIRO — Time does fly. Example: Just three years ago, in the summer of 2013, freestyler Katie Ledecky won her first world championship title at 16 years old. It came at the core distance—400 meters—of a repertoire that has yet to find its limit, and marked a breakthrough as much mental as physical. After becoming just the second female to snap the race’s four-minute barrier, she turned to coach Bruce Gemmell with what he calls a “beaming grin”, and said, “’I had no idea that I could go that fast!’”

Gemmell, 55, prizes the moment because it gave a glimpse, amid Ledecky’s dauntingly mature rise, “of that nine-year-old kid in her,” he says, “who had won some summer league freestyle race: ‘I didn’t know I could win the blue ribbon…’”

She certainly knows now. Ledecky owns nine of the top ten 400 times in history—all of them sub-4:00—and after missing out on breaking her two-year old world record in Sunday’s Olympic prelims by .34 of a second, assessed matters with a coroner’s cold regard. “That’s the easiest it’s felt for me under four minutes,” Ledecky said. “So I think it bodes well for me tonight.”

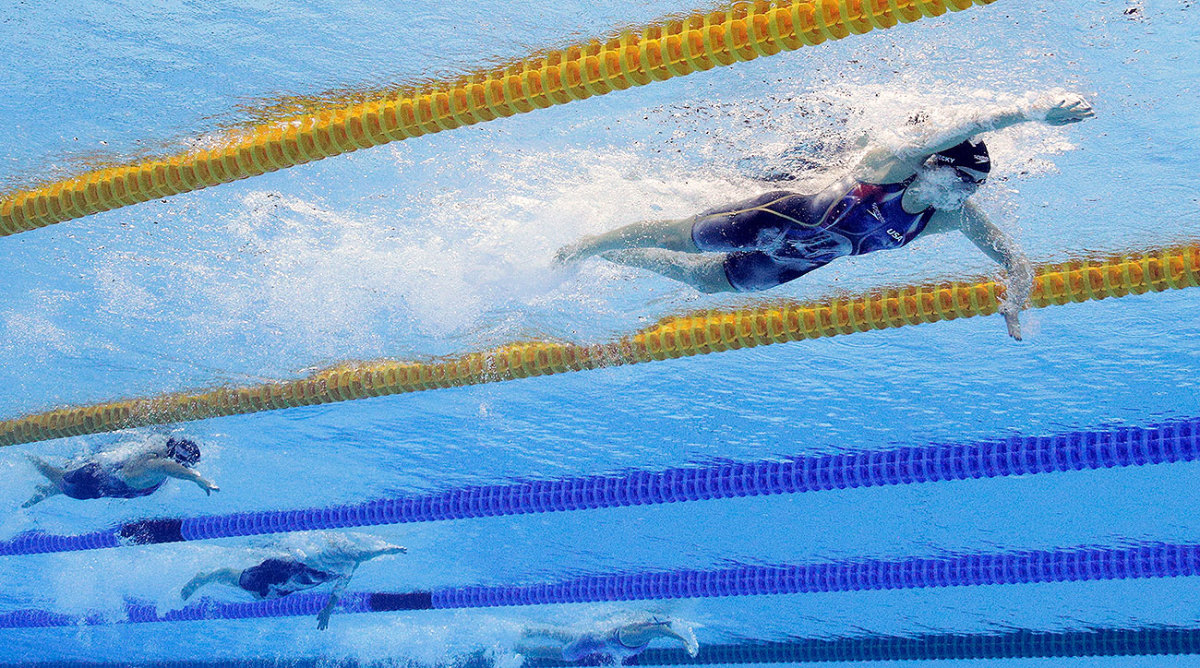

Understand: Coming from her, such words amount to a chest-pounding roar—and she backed it up. Leading Sunday night’s final from the start and winning by nearly five seconds, Ledecky crushed that world record (3:58.37) by nearly two seconds, finishing in 3:56.46 to win the final for her first individual gold medal of the 2016 Olympics. When bronze medalist Leah Smith took in the time, she cried, “Three-fifty-six?” like one repeats the most shocking news. But it sort of wasn’t.

“I knew she was going to win, but I didn’t see it until I hugged her and then I was just so excited for her,” Smith said of Ledecky. “I’ve been cheering for her the past month while she’s been doing amazing things in practice, so I knew it was coming. It was just a matter of when and how fast she was going to go.”

True, it’s not like this wasn’t expected. Ledecky came into Rio a virtual lock to win four medals—most of them gold—and that prospect only brightened with the silver she won after unexpectedly anchoring Team USA’s 4x100 relay on Saturday. Indeed, heading now into the meat of her schedule, the 2016 Games are shaping up as the realization of all the scary-good potential Ledecky unveiled in 2013. She won four world titles and set two world records in Barcelona, a performance that forced her and her coach, not to mention the powers at USA Swimming, to come to a new truth and recalibrate.

“I’ve never coached anyone as good as Katie,” says Gemmell, who began working with her the year before, “and neither has anyone else.”

That’s when he began getting not-so-subtle messages—Don’t screw this up.—from his mentor, 2012 Olympic head coach Jon Urbanchek, and USA Swimming national team director Frank Busch. “Frank very conspicuously put his arm around my shoulder and said, ‘Bruce, let’s talk about what you think about the next three years…’ and we talked about everything from overwork to too little work to all the things that have derailed 16-year old female swimmers in the past,” Gemmel says. “It was an easy conversation—but pointed.”

Gemmell then convinced Ledecky that the 400’s then-world record, 3:59.15—set in 2009 by Italy’s Federica Pellegrini, before the full-body suit ban—was more than attackable. Setting goals for the next four years, they quietly decided to shoot for an astonishing 3:56 by Rio; no one even in her family knew. Ledecky went on to set 11 world records at different distances between then and Sunday night, but it’s a sign of her ambition that she may consider them mere milestones.

“I always rely on him to help me set my goals, because you never know what’s possible unless you hear somebody else say it,” Ledecky said after Sunday’s win. “We have our goals for this week and we’re still working towards them. We finally hit one. It feels really good.”

Indeed, every move made, from Ledecky’s decision to take a gap year before heading to Stanford to her training schedule to the strategy of waiting until after U.S. trials to fully taper, brought her to Rio healthy, unstressed and supremely primed. But Gemmell would be the first to admit that Ledecky makes his job easy. Her capacity for pain and work is already the stuff of legend, even to male swimmers. When one ended a workout with Ledecky this spring at the Olympic Training Center by saying, “It’s been a long time since I felt I was going to throw up in practice,” Ledecky could only laugh.

“I feel that way about four times a week,” she said.

If anything, Gemmell finds himself seeking small ways to take her foot off the gas. In May, Ledecky’s brother Michael, with whom she is remarkably close, was set to graduate from Harvard. Ledecky worried about missing just one day of practice for the trip. “I had to encourage her: ‘No. Go,’” Gemmell says. “’We’ve done enough work; it’s okay to have the ice cream that you want. In the water you can still go full-bore.’ There’s no reason to pull her back on that.”

Stunningly, it may be that the high-pressure, high-glare atmosphere of these Olympics allows Ledecky to achieve that balance better than almost anywhere else. Thrust into a world where she’s hardly the biggest name (NBA stars Kevin Durant and Draymond Green wandered into the swim coaches quarters in the Athletes Village before Friday’s opening ceremony, looking for a place to change), she gets to revel in a dynamic that allows her to almost blend in.

“There’re not a lot of seats for the team in the stands and we knew that going in,” Ledecky said. “We wanted to have a great team atmosphere back in our area at the warmdown pool, so we have a cowbell that rings every time USA swimmers go up to the ready room. We’re annoying some teams, but it always reminds whoever’s on deck, and you get out real quick and say ‘Good luck.’ So we have a great team atmosphere and… USA. Let’s go. We’re rolling and excited for the rest of the week.”

In fact, Ledecky and anyone who knows her agree that a relay was by far the best way for her to start these Games—and point to her stunning 52.64 in Saturday’s 4x100 qualifier as evidence. She likes the hangout, playing cards and Rummikub, the singing of a “High School Musical” tune with teammates in the ready room. And she loves the responsibility of people depending on her.

“I got this covered,” Ledecky texted her mom Saturday afternoon, after she learned that she’d be anchoring, for the first time in an international meet, the 4x100 final against the mighty Australians. “NBD if we don’t beat them. But we have to have that gold medal mindset.”

Team Australia won in world-record time, but Ledecky was closing on the world’s No. 1 sprinter, Cate Campbell, near the end; she hardly looked like a novice. No, the only instance when Ledecky seemed uneasy came afterward, when a reporter asked teammate Dana Vollmer about her in the mixed zone. “It’s absolutely amazing, I think, to have the versatility to have all those different speeds in four different races; it just says a huge amount for her athletic ability,” Vollmer began.

Ledecky, standing right next to her, stiffened. Her face went blank, and she stared at a spot on the wall. “I had no doubt, when they put her on in prelims that she was going to bust out something amazing,” Vollmer went on, “and it was really fun to watch and to know that she was going to be on it at night. I feel like she has that amazing ability to change her rhythm for such a different race. And I know that she is an absolute fighter.”

But the moment passed. Ledecky didn’t get to sleep until 2:45 a.m. Sunday, yet came back for the 400 later that evening clearly energized. She’s not 16 anymore, but still young enough where anything is possible. “She’s grown up,” Gemmell said, standing in an arena hallway arena after Sunday night’s final. “It’s experience, it’s maturity. It’s being wise…”

At that moment, Ledecky passed by and Gemmell called out, loud enough for all to hear, “...Wise beyond her years!” She looked back over a shoulder then, grinning and eyes wide. That’s when you could see it again: The little girl excited by all that she might do.