In a Stalled Sports World, Everyone's Day with Coronavirus Comes

Captain Tommy never lets the facts get in the way of a good story. He’s quite literally got whale tales. He’s heard the great mammals roar around him in the vast ocean, like that scene from "Jaws," the one with all the scars and all the singing, when they’re drinking hard whiskey around a creaky old table in a dungeon-like cabin of a swaying vessel. That’s how I imagine Captain Tommy and his deckhands, the tide taking them to their next fishing hole, only moonlight paving the way.

Captain Tommy has the best stories. The one about the giant squid he snared in his net. The shark flopping around on the boat’s deck. Embellished or not, Captain Tommy has real fish tales, gathered from 40 years as a shrimper on the waters of the Gulf of Mexico, gone months at a time and returning to stink like the inside of a trout. In those days, Captain Tommy was more comfortable on the ocean than the land. He understood it out there, embraced its solitary nature. While most struggle to gain sea legs, Captain Tommy, later in life, had to find land legs.

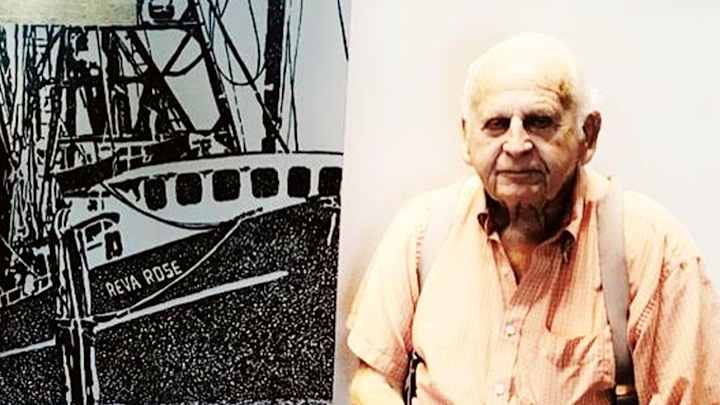

He eventually found them, then stumbled upon a twice-divorced mother of three, married her, cared for her children and finally had his only child. He named his shrimp boat after her. The Reva Rose is still sailing today in fact, captained by a different man. Captain Tommy’s commandeering days are long gone. He’s old now, turned 87 last October, and it’s quite a miracle he’s made it this far. His feet are barnacles, his vision is shot and his hearing is toast. It sucks growing old, but it’s part of life.

What happened to Captain Tommy last weekend is, for many, part of life, too. He suffered a major stroke affecting both sides of his brain. Captain Tommy’s brain was the thing he had going for him. While many of his physical tools dulled, his mind stayed sharp. The stroke has left him in a hospital without the ability to speak or swallow and in a fluid mental state. Maybe worst of all, he’s alone. His family has been ordered to stay away. Captain Tommy is sharing a hospital with six coronavirus patients.

Let’s be honest, this is the real reason we’re here discussing Captain Tommy on the pages of Sports Illustrated, where the virus’s impact on human beings is more important than anything about a ball and a glove. The last time his wife saw Captain Tommy, he was in the ER after having been rushed to the hospital. She got 10 minutes before medical personnel ushered her off the property. It’s not safe for you here, ma'am. She’s 80, and while it’s become evident the virus isn’t all that particular, it’s most deadly for seniors.

For fear of the pandemic spreading, many families of those hospitalized across this country cannot visit their loved ones. Patients are battling quite normal illnesses, fighting at times for their lives, even dying, while around them are only strangers in scrubs. So there was Captain Tommy, left all alone. Can you imagine waking up without the ability to talk or swallow, confused, hooked to machines, hungry, thirsty, and you look around to find no one in the room you recognize? No friends. No family. No one. This is what the coronavirus has done, humans enduring some of their most traumatic moments in life without a parent, spouse or sibling by their side. Nothing by their side. No flowers. No balloons. No cards. It’s all too risky to send. It could be contaminated, and plus, the florist shops are closed. This is a lonely place: a hospital room, a bed, a patient.

The message here is that the coronavirus can impact you or your loved ones even without anyone contracting it. This plague has wrapped its ugly claws around the world, squeezing the happiness out of us all. The virus doesn’t have to bite us, doesn’t have to bite our child or our parents, for us to feel its venom. If this story makes just one person understand that, it’s been worth it, all the tears, all the heartache.

Luckily, Captain Tommy’s family has a white knight, a doctor who’s a longtime friend, and he’s sat by Captain Tommy’s bedside and called the man’s family. Their voices come crackling through, and Captain Tommy’s eyes well with tears. This is no small feat, a shrimp boat captain crying. He can hear their voices, and if they listen hard enough, emerging in a low grumble, they can hear his. No. Yes. I’m good. “Did you hear him? He said, ‘I’m good!’” the doctor friend yells gleefully to the family, another reminder that they’re not here.

This is a close-knit family, one that gathers weekly around a card table, drinking cheap beer and feasting on fresh Gulf catch. They’re originally from south Louisiana stock, social butterflies with a passion for boiled crustaceans and fried fish, reared on the captain’s catch. Captain Tommy was named Shrimp King back in the 80s, and if you’re wondering what that means, no, I don’t know either. But, in his home, there is a portrait of him uncomfortably wearing a crown atop his thinning white hair. Captain Tommy isn’t necessarily the regal type (in fact, I’m certain he’s killed a man or two somewhere along the way), but he was a dang good shrimper and he’s an even better chef. Boy, Captain Tommy can cook, cook you right out of your own kitchen, his gumbo, jambalaya and grilled brisket as good as any. Even in his old age, he’s still got it.

Surely he’s looking around now wondering about that family of his. What’s harder, the pain of a loved one’s illness or the hurt that they are suffering alone? “I keep thinking that he thinks we abandoned him,” Captain Tommy’s daughter says. “He probably thinks, ‘Where the f--- are these people?’”

Captain Tommy is alone again, like he was on the water for so many years, hopefully this time embracing a different kind of solitude. That hospital bed is no boat, but maybe he feels the ocean’s tides, his sea legs losing their rust as he drifts toward recovery. He’s battling the toughest current he’s ever faced. Come on, Captain Tommy. Come on.

See, I have a vested interest in Captain Tommy, all alone in that room. I don’t want him to be alone. I want to hop on a jet and burst into that hospital, his family in tow with balloons and flowers, fried shrimp and gumbo, beer and bourbon. Screw that damn virus! I want to sit next to the man who I’ve seen bite through pork chop bones, a guy who playfully threw me into the ocean from that boat of his, who has boiled me the biggest lobsters I’ve ever seen, who taught me to make a roux.

I want to see my grandpa.

Ross Dellenger received his Bachelor of Arts in Communication with a concentration in Journalism December 2006. Dellenger, a native of Morgan City, La., currently resides in Washington D.C. He serves as a Senior Writer covering national college football for Sports Illustrated.