On-field achievement gives Rivera edge over instinctive pick Robinson

Conventional wisdom suggests a list of the best baseball players by uniform number should include the lone athlete in pro sports history whose number has been retired by an entire league.

The de-facto choice for No. 42 is Jackie Robinson. Put it down with a Dodger-blue Sharpie, right? Decades after his 1947 shattering of baseball's color barrier, the Hall of Fame second baseman remains a sacred figure in American life.

Certainly, on a list of the most important players by number, Robinson is a slam dunk.

On a list of the best players ... not so much.

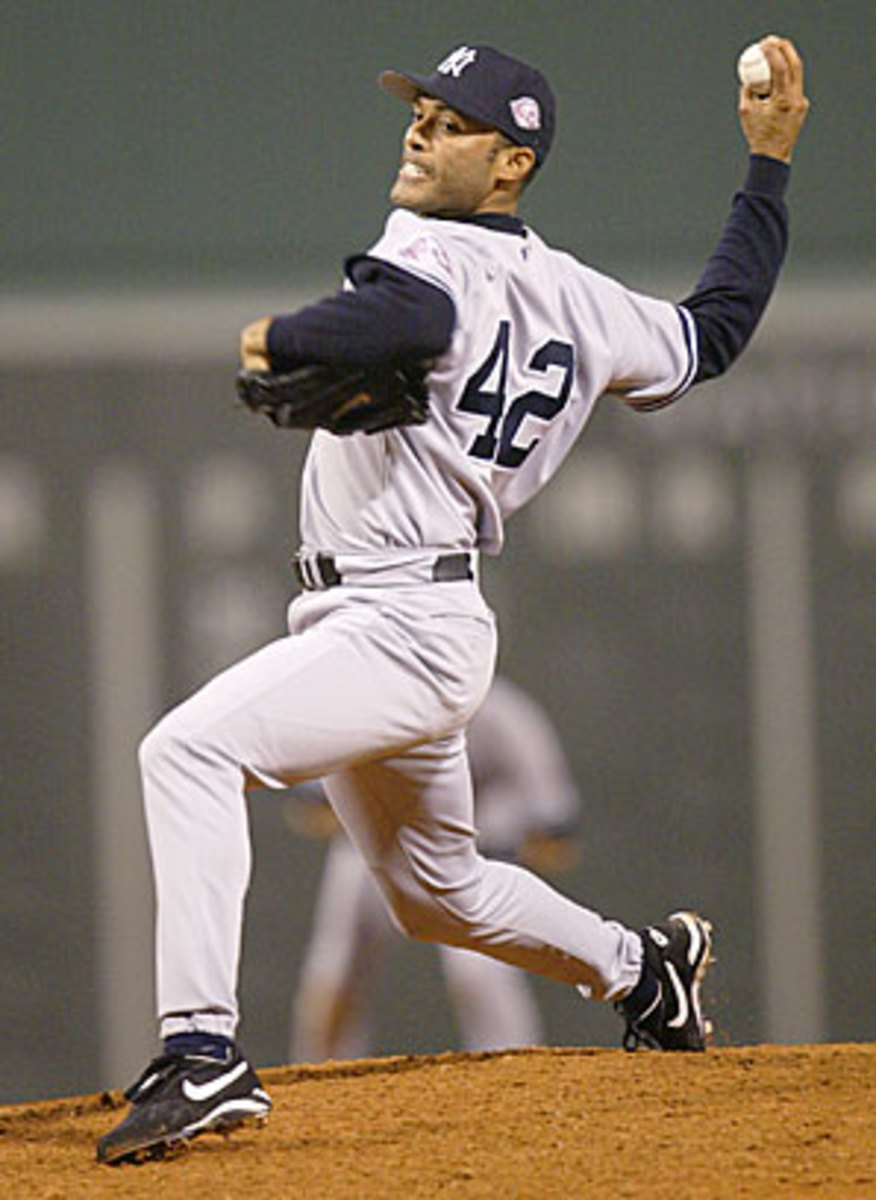

Baseball's best No. 42 is Mariano Rivera, and as the last active player still wearing the digits due to baseball's 1997 decree, the 38-year-old right-hander need not worry about any future challenge to the distinction.

Because baseball is played on grass and not paper, it's impossible to compare Robinson and Rivera in a vacuum. One (Robinson) spent his entire career in the National League; the other is an American League lifer. One played in the field, the other pitches in relief. One competed during baseball's golden age, the other during its steroid era. And, most important, Rivera has enjoyed a lengthy and unimpeded career; Robinson didn't join the Dodgers until after his 28th birthday, segregation having precluded the front end of his major-league experience.

There is no discounting Robinson's courage and composure in the face of unimaginable bigotry -- a trait famously described by Branch Rickey as "the guts not to fight back." But if we limit the scope of the argument to on-field performance and look at both sets of numbers, the case for Rivera reveals itself.

Rivera stands alone as the most dominant closer of his generation. He was the most consistently valuable player on the fin de siècleYankees, the greatest baseball dynasty since the advent of free agency. Among active players, there's not a more obvious first-ballot Hall of Famer. With a Koufaxesque aura of invincibility in the postseason pressure-cooker, Rivera has locked down four World Series titles to date -- three better than Robinson's Dodgers. He has amassed the all-time playoff records for most saves (34) and lowest ERA (0.77). With 451 career saves through Friday, Rivera ranks third on the all-time list and will retire in second or first.

Statistically, Robinson is a borderline Hall of Famer. His average single-season numbers -- .311 batting average, 14 homers, 73 RBIs and 20 steals -- are excellent but not jaw-dropping. After winning the inaugural Rookie of the Year award, Robinson played just nine more seasons in the majors, winning a batting title, a pair of stolen-base crowns and the league's MVP award in 1949. Certainly, his extraordinary peak seasons from '49 through '53 rank favorably against any second baseman this side of Rogers Hornsby. He could run, throw, field, hit for average and power, rattled opposing pitchers with his aggressive base-running and posted strong numbers at the plate in an era when the second baseman was an afterthought offensively.

But ... 10 seasons?

It's simply too small a body of work to include Robinson on the short list of the best players at his position. And while it's a tragedy his career was abbreviated for regrettable reasons, it's also unfair to mount a case against Rivera using the numbers Robinson might, would, could or should have posted.

If this argument strikes you as sacrilege, remember, the author is a child of the '80s. I came of age in a society where racial equality was taught not as lofty ideal but inexorable fact. Is race still a relevant issue in America? Of course. But civil rights is something my parents' parents hashed out. Call it new-school, but my generation tends to view sports as a meritocracy, where batting average trumps bloodlines.

This doesn't mean I have any less an appreciation for the horrors the second-greatest No. 42 endured during his Hall of Fame career. But if Robinson suffered so we could live in a nation where athletes are not judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their stat lines, would anything short of a purely by-the-numbers approach honor his memory?

Agree or disagree? Give us your take here.