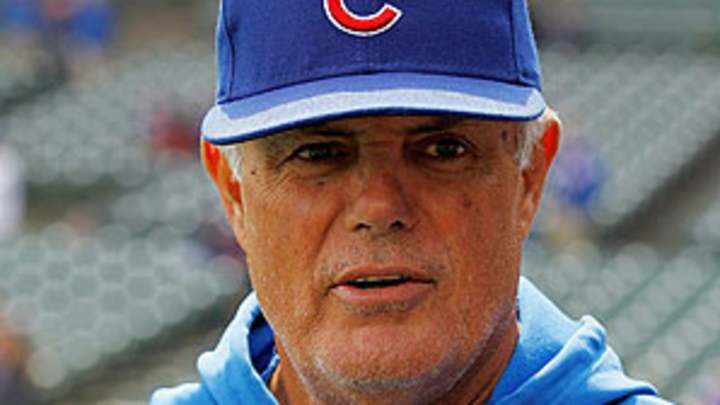

Why Lou Piniella is a Hall of Famer

Piniella, 66, retired Sunday in the midst of his fourth season as manager of the Chicago Cubs. If it is, as he says in his statement, "time to enter a new phase of my life," it will be the end of a 23-year career in which Piniella has never quite gotten his full due as a strategist. Would you have even guessed that Piniella has managed for 23 years? Since he debuted as a manager with the Yankees in 1986, there have been just two seasons (1989 and 2006) that Piniella wasn't in one dugout or another, a tremendous stretch of longevity that was, for the most part, very successful.

Managers generally don't get elected to the Hall for their stats, but Piniella's stand up to scrutiny. He has won 1,826 games as a manager, 14th all time. Of the top 20 in managerial wins, all but Gene Mauch and Ralph Houk are either in the Hall or on their way; Mauch had a career record below .500 and Houk never managed a team to a pennant or division title after his third season in the dugout. Piniella's total of 3,517 games managed is 13th all-time, and he is one of just 14 men in history to have managed at least 3,000 games and posted a winning percentage above .500. Piniella managed one World Series champion, the 1990 Reds; the team that set the record for regular-season wins, the 2001 Mariners; four other division champs and one wild-card team.

The first thing that comes to mind with Piniella is his temper, which was legendary. Watch any highlight show today, and you'll see clips of Piniella yelling, screaming, throwing bases...a caricature of a manager. That wasn't what made him great. Piniella did tangible things that made his ballclubs better, such as abandoning the single-closer model in 1990, when he had three terrific relievers in Randy Myers, Rob Dibble and Norm Charlton and rode them to a World Series title. Later in his career he would become a master of the running game, his Mariners and Devil Rays teams repeatedly posting high success rates on the bases as he split his roster into guys who could run successfully -- and were allowed to do so -- and everyone else. He would shut it down if the personnel dictated it; this year's Cubs have Ryan Theriot with 16 steals in 21 attempts, and no one else with more than four steals or eight attempts. Piniella has exemplified practical sabermetrics -- an understanding of the costs and benefits of the stolen base attempt -- and gotten no credit for doing so.

Piniella isn't without his flaws, most notably a lack of deftness with young players. From Dan Pasqua in New York to Paul O'Neill in Cincinnati to Bobby Ayala in Seattle and a whole host of Devil Rays, Piniella showed impatience and even anger toward players who didn't hit the ground running. He integrated a number of Japanese players, most famously Kazuhiro Sasaki in 2000 and Ichiro Suzuki in 2001 in Seattle, but his inability to manage young players remains the biggest hole in his record. That flaw contributed to the darkest period of his career as well, a three-year run in his hometown of Tampa Bay that produced little but frustration for Piniella and the franchise. Like Jim Leyland in Colorado, Piniella took a job for which he was ill-suited and to which he was not fully committed. His time with the Rays is the only stop in his career in which he never won 90 games in a season, never contended, and one of just two stops (the Yankees being the other) in which he never won a division title.

Piniella may not feel like a Hall of Famer to some people, the same ones who argue that Tim Raines or Alan Trammell or John Smoltz don't feel like immortals. Piniella, like those players, suffers in part by having contemporaries who were among the very best who ever lived. Smoltz pitched in the same era as Roger Clemens, Greg Maddux and Randy Johnson, pitchers who broke the curve for mound greatness in the waning days of the 20th century. Similarly, Piniella's managerial contemporaries included Tony La Russa, Bobby Cox and Joe Torre, three men who will unquestionably be inducted not long after their retirements and who rank 3-4-5 on the all-time wins list with 16 pennants and seven world championships among them. That's not the standard and it never has been, and Piniella shouldn't be held to that. Piniella is Smoltz, or Tom Glavine or Mike Mussina, an all-time great never quite appreciated as such, due to context. Like La Russa and Cox, Piniella succeeded in different places in both leagues with different types of teams, and adapted along with the game over a quarter-century.

It's entirely possible that the story changes, that Piniella leads a furious Cubs charge to the NL Central crown or that he comes back in two years to helm the A's to a pennant. He doesn't need those markers, though. Since 1986, Lou Piniella has been making his teams better, and that kind of track record deserves not just our acknowledgment and our appreciation today, but the highest honor baseball can confer upon him: Hall of Famer.

Joe Sheehan has been contributing to Sports Illustrated and SI.com since 2007. Prior to that he was a founding member of Baseball Prospectus and a contributor to ESPN.com. He's been a regular guest on ESPNews' "The Hot List", MLB Network's "Clubhouse Confidential" and "Fantasy 411", and "SportsTalk" on the NBC Sports Network. He's probably talking baseball on the radio somewhere right now. A graduate of the University of Southern California, Joe lives in New York.