Lacking developmental league, many NFL hopefuls have few options

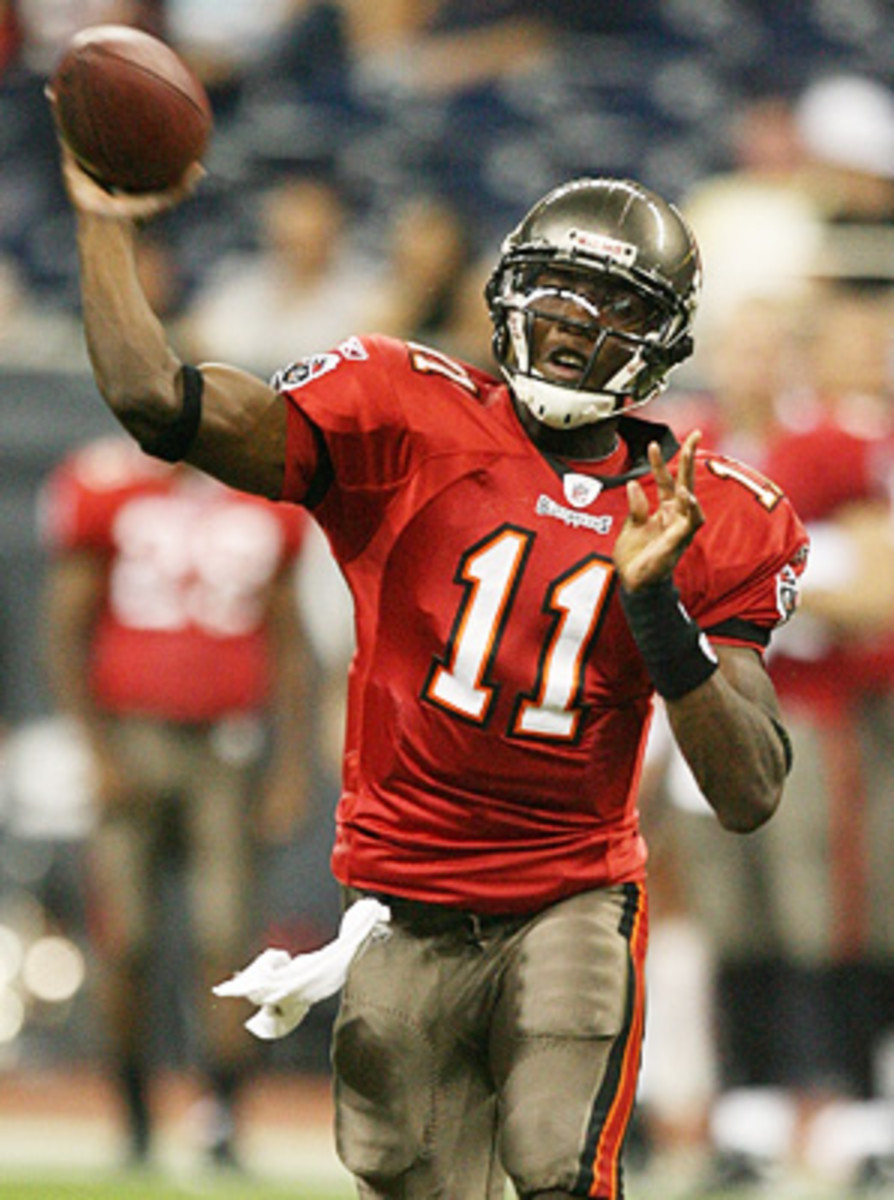

Josh Johnson was selected by Tampa Bay out of the University of San Diego in the fifth round of the 2008 NFL Draft.

Bob Levey/Getty Images

Before signing with the Cleveland Browns the day after Christmas due to a pair of injuries at the quarterback position, Josh Johnson treaded an uncertain path back to the NFL that was nearly a season long.

The day after Thanksgiving, instead of preparing for the next week's opponent as a member of a team in the thick of the NFL playoff hunt, the free-agent was attending his Oakland, Calif., high school alma mater's league championship game at a local community college.

Prior to that, the 26-year-old Johnson was ambling up and down the boundary of a field in Sacramento in street clothes for a United Football League game on a warm weekday evening in early October. Johnson, the marquee signee of the Mountain Lions franchise in the fledgling, four-team pro league, could only observe the Week 3 contest after seriously injuring his knee in the first game of the season. Like the rest of the undersized Wednesday night crowd, he watched as former Buffalo Bills reserve quarterback Brian Brohm tossed an 81-yard touchdown to lead the visiting Las Vegas Locomotives to a 20-9 victory.

After the Tampa Bay Buccaneers selected Johnson out of the University of San Diego in the fifth round of the 2008 NFL Draft, he found mostly spot play and relief duties with the Bucs behind eventual starter Josh Freeman, appearing in 26 games in four years. At the end of his rookie contract following last season, Johnson became an unrestricted free agent and looked for a chance at increased playing time with one of the league's other 31 teams.

He caught on with the San Francisco 49ers">49ers under his former college coach, Jim Harbaugh, agreeing to a two-year contact in March. In spite of a solid preseason, including converting 9-of-14 passes for 125 yards, two touchdowns and no turnovers to go along with 50 yards rushing in the final preseason game, Johnson was one of the team's last cuts. With few available options, he assumed all of the risk to his health and signed on with the UFL team in September, which netted him game checks of $3,500. In the NFL, a player with Johnson's experience could make no less than about $41,000 per game in 2012; a rookie, no less than approximately $23,000 each week of the season.

The other second- and third-tier choices, the Canadian and Arena Football Leagues, were potential alternatives, but because of their own set of snags -- the CFL has a two-year minimum contract requirement, each league has slightly different rules and varying levels of talent, and the timetable for each directly conflicts with the NFL -- neither was ideal. With just an eight-week schedule plus a championship game, the UFL was designed to end in time for its top players to still find homes in the NFL in the same season after roster attrition takes hold later in the year.

"Possibly," Johnson said in early December of joining these other leagues, "but I don't feel like I'm to that point of my career yet. You think about it, but then you understand what time frame that those leagues are taking place. The AFL is about to start up right now. Or go to Canada and you've got to be locked in for two years. The NFL ending in January, there's an opportunity for them to pick you at the end of the [UFL] season. I'm trying to get back into the NFL, so right now everything is dictated around the NFL schedule for me."

Since kicking off its inaugural season in 2009, the UFL has been the latest American professional football spin-off trying to succeed as a lesser version of the NFL, in markets where the established football conglomerate does not have a strong presence. In addition, because the NFL has not had a developmental league since it folded its European extension mostly for financial reasons following the 2007 season, the UFL also provides both former college players still attempting to break in, as well as the league's washouts trying to make it back, a place to develop and play.

The upstart league hit the skids in late October, however, and was forced to postpone the second half of its season until the spring due to a lack of finances. After that, the plan as of now is for the UFL to resume in fall 2013. Just prior to the deferral announcement, reports surfaced that players and coaches had not been paid for weeks. It was also around then that Marty Schottenheimer, coach of the champion Virginia franchise the previous season, filed a lawsuit alleging $2.3 million in unpaid wages. Former Mountain Lions coach Dennis Green filed a similar complaint in July, claiming more than $1 million in back pay.

Among many trying to use the league as their ticket to the NFL, Johnson is one of the few to ultimately find success. Despite regular debate about the quality and competitiveness of the UFL, some have said they believe many of league's players are talented enough to play at the highest level. Jim Fassel, former NFL head coach and now the longest tenured coach in the UFL, with the Las Vegas Locomotives, is one.

"A lot of individual players here can go and play in the NFL," said Fassel. "I spent a lot of years in the NFL and I know what it is they're looking for. At the end of the day, there are a lot of guys, I know on my team, that they could have played for me."

"It felt like football to me," added Johnson. "It just wasn't 60,000 people in the stadium compared to an NFL game. There's a lot of good players who don't have the opportunity to be on an NFL roster because of the small amount of guys that they allow to have on the rosters. So I feel like if they would have kept that league going, that's a good opportunity for guys to not only stay in shape -- not only stay in game shape -- but you're playing football and also getting a little bit of exposure for them to see you under actual game situations because some guys never even get the opportunity to play on an NFL team. They just practice."

The practice squad is another route to the NFL. In fact, the man currently ahead of Johnson on the Browns' depth chart is Thad Lewis, a four-year starter at Duke now in his third-year as an NFL practice squad player after two seasons with the Rams and this year in Cleveland. Were he to get the nod on Sunday against Pittsburgh if Brandon Weeden and Colt McCoy are out and Johnson doesn't beat him out in under a week of practice, Lewis would make his NFL debut.

Since 1989, the league has allowed each franchise to maintain a practice squad of up to eight players for what is essentially a scout team, but is often viewed as mini developmental unit. Any team is granted a ninth member on the squad as part of the league's International Development Practice Squad Program, so long as the player is foreign born and their primary residence falls outside of the United States.

For the 2012 season, these practice-only players make $5,700 per week, but because they are not considered members of the active roster, are not entitled to a pension or other benefits. Players are eligible to join the practice squad if they do not have an accrued season of NFL experience, which is defined as six games on an active roster, or as long as they are a free agent who was active for fewer than nine games in their one accrued season. For all intents and purposes, someone can be on a practice squad for up to three seasons, and it is fairly common to see a player like Lewis elevated from this designation to the active roster for a game based on injuries, then waived back to the practice unit by the following week.

Players like Johnson, who have multiple seasons of NFL experience, are not eligible to join a practice squad, though that would undeniably be a step backwards in their careers. For instance, it is difficult to imagine other players clamoring to get back into the league, such as Vince Young, Terrell Owens or Chad Johnson, joining a practice squad. But as illustrated with the Browns this week, the position does fill a need, as well as provide less accomplished players a chance to eventually make a roster.

Still, before Cleveland picked him up, this leaves veterans in Josh Johnson's position at a loss for options. Where NFL Europe helped players to mature and polish their skills in what was the league's feeder system, no such track currently exists, and its former value is hard to argue. In 2006, 201 players with NFL Europe experience appeared on active NFL rosters. In 2004, it was even more at 262. There have also been 27 quarterbacks to start in the league after time overseas, including Jake Delhomme, an alum of both the Amsterdam Admirals and Frankfurt Galaxy before leading the Carolina Panthers to the Super Bowl in 2004.

Former NFL Europe quarterbacks also include Kurt Warner, Jon Kitna, Brad Johnson and Shaun Hill. Several upper echelon kickers have been the benefactors of the time abroad too, namely David Akers, Adam Vinatieri and Matt Bryant. Among others, a couple more notable for NFL Europe experience are Fred Jackson and James Harrison.

In the absence of NFL Europe, Fassel thinks the UFL could make the perfect feeder system for the top pro league.

"It should be," he said. "I think it could work out well for everybody that way. It's the only major sport that doesn't have a developmental league or minor league. It's the only one -- and it's the one with the most injuries. It'd be as much up to the NFL, and us too. But you know, any year there could be some talk."

NFL commissioner Roger Goodell broached the idea of re-launching a developmental league in 2009, and once again called doing so a possibility in May, but offered few details.

"We have talked a great deal about the idea of a developmental league," Goodell said at the league's spring meeting. "We actually think that there could be a role for that. Particularly with the changes in the Collective Bargaining Agreement, the limited amount of time the younger players have to either be evaluated or develop their own skills. It is something we will continue to pursue."

As one of the last remaining chances for players to break into the league, the NFL presently offers a handful of regional combines after acquiring a smaller outfit in 2011. If a player performs well enough there, he is brought into an invite-only super regional event, which for this upcoming offseason will take place in Dallas in April. Last year, four players were drafted out of the 162 invitees with another 63 signed to preseason 90-man rosters as undrafted free agents.

Johnson had a few NFL tryouts, with Houston, Seattle and Chicago, after recovering from his knee injury and leading the Mountain Lions to their only win of the season before the UFL shuttered. With no workout, he then signed with Cleveland right off the street. However, beyond the one game to end the season, as the Browns will once again miss the playoffs, there are no guarantees for Johnson who will probably function as a reserve and not play. More than likely, assuming it's not with Cleveland, he will then sign with another team during the offseason for at least one more opportunity in the league when rosters expand.

As a four-year veteran, Johnson is better off than the many in a similar circumstance in that he achieved a pension from the league, which requires at least three games on an active roster for four seasons. While Commissioner Goodell and NFL Players Association executive director DeMaurice Smith have in the past squabbled over what the average length of a player's career actually is -- Smith says it's closer to three years, Goodell, six -- there is no question several who have played in the NFL move on without reaching the threshold for long-term benefits and health care.

Like any number of those like him though, with little or no support from the league after leaving college early to chase their NFL dreams, Johnson acknowledged that he's not sure what he would do for a living if he continues to be unable to secure a long-term option in pro football. Nonetheless, he maintains that pursuing a bigger role in the league after ultimately not re-upping with the Buccaneers was the correct choice.

"With the situation at the time, what I wanted for myself and for my life, that was the right decision," he said. "Right now, it might not look like it, it might not reflect that way, but hey, you live and you learn, and you choose that path that you have. We create our own lanes for the most part, as much as we can. But I understood the risk I was taking for everything I did. That's just how it works sometimes."

Johnson also recognizes that the NFL, which right or wrong is relatively open about the fact that it primarily uses the NCAA as its minor-league system, is not necessarily there to do many favors.

"They do what they feel is necessary for them," he said. "It's a business. Business decisions sometimes come before personal or football decisions, so you've just got to take it."