Amid Developing Science, Does Big Ten's 21-Day COVID Protocol Still Make Sense?

Less than two months ago, Barry Alvarez listened to conference medical experts in the Big Ten describe the labyrinth of heart-related screenings necessary to clear an athlete who has contracted COVID-19.

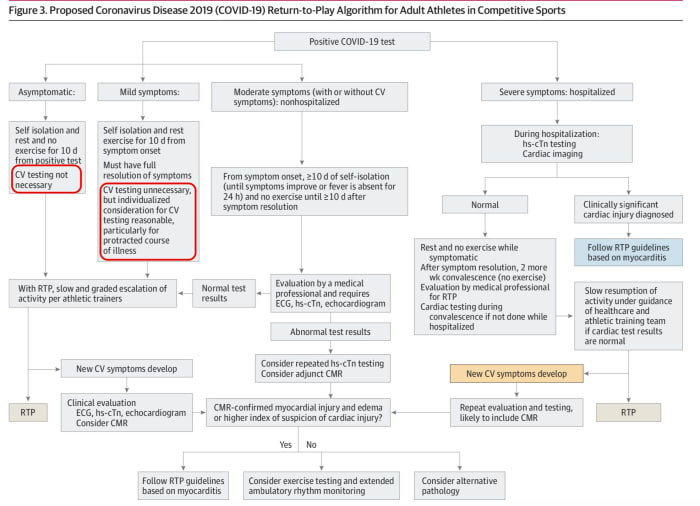

The athlete would need to jump through four proverbial hoops, all of them ensuring that the virus did not impact the heart, before returning to activity. They’d need a troponin blood test, which measures the level of cardiac-specific troponin in the blood to help detect heart injury. They would also need an EKG, which records electric signals in the body’s most important, blood-pumping muscle. In addition to that, they would need to be administered an Echocardiogram, which uses ultrasound to generate an outline of the heart’s movement. And lastly, they’d need a cardiac MRI.

Because of the breadth of the screenings and the fact that no heart test could be administered until two weeks after an athlete contracted the virus, the conference was also mandating a strict return-to-play timeline. All positives were suspended from play for 21 days.

“I was surprised,” says Alvarez, the Wisconsin athletic director and former Hall of Fame football coach. “I thought 21 days didn’t quite sound right.”

Seven weeks later, Alvarez finds his school at the center of maybe the strictest return-to-play COVID-19 mandate in American sports. Wisconsin’s starting quarterback, Graham Mertz, and backup quarterback have tested positive, according to various reports, along with at least four more players. They will miss three weeks of activity, or one-third of the Big Ten’s nine-game 2020 season (The Badgers' game this Saturday vs. Nebraska has been called off due to Wisconsin's cases).

Mertz helped the Badgers win their opener vs. Illinois, then tested positive for COVID-19.

Jeff Hanisch-USA TODAY Sports

In the same week that the 21-day policy ensnared one of the league’s high-profile players, some of the nation’s most acclaimed sports cardiologists published a revealing paper that may undermine the conference’s return-to-play rule less than two months after its adoption.

The nine-page report, heralded by physicians across the country, indicates that doctors are finding so few heart abnormalities in COVID-positive athletes that they are no longer recommending any cardiac screenings for those who experienced mild symptoms or no symptoms.

As recently as September, cardiologists were mostly recommending full-scale heart screenings in the absence of workable data—what some might call an appropriate, cautious approach to a novel virus’s impacts on such a significant organ.

With more data, research and experience, they are reversing course. It speaks to the greater theme of a COVID world: Everything is fluid.

“We’re building the ship as we sail,” says Matthew Martinez, a co-author of the paper and the medical director of sports cardiology at Atlantic Health System in New Jersey who is the league cardiologist for Major League Soccer.

“The vast majority of athletes are falling into the asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic group. The yield and events [of heart abnormalities] are small based on limited outcome data—very, very small,” Martinez said in an interview Monday. “We are seeing that in the NCAA and also professional sports.”

According to the data, he estimates that well less than 1% of COVID-positive athletes who experience mild or no symptoms are showing cardiac issues such as myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart found in some post-virus patients.

Out of hundreds of college athletes, doctors are finding heart abnormalities in the single digits, “if we’re finding them at all,” he says.

The report was published Monday in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a peer-reviewed medical publication that’s in its 132nd year and is held in high esteem among medical industry experts. Sports cardiologists contacted this week described Monday’s article as excellent and sound, but cautioned that data is still incomplete. A full study is expected later this fall when more numbers are crunched.

“The article is trying to restore some semblance of order to the universe with a rationale approach,” says Michael Ackerman, a genetic cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota who briefed both the Big 12 and Conference USA in August regarding the myocarditis scare that swept across college sports.

Myocarditis, along with the uncertainty of the virus’s impact on the heart, was a significant factor in initial decisions by four conferences to postpone the 2020 fall football season, most notably the Big Ten. Conference leaders voted Aug. 11 to push the football season to spring before re-examining the issue and reversing course roughly six weeks later on recommendations from its medical advisory board—the same board that had originally thought it too dangerous to play in the fall.

“When we made that original decision to postpone, myocarditis was everywhere in the news,” says Morton Schapiro, Northwestern’s president and the chair of the league’s highest policy-making body of chancellors and presidents. “That is and was very scary. I don’t know that if it hadn’t been for myocarditis whether the medical professionals would have recommended a different course of action.”

In September, Big Ten doctors only gave approval to restart the season with an aggressive set of protocols: daily rapid testing and that labyrinth of post-virus cardiac screenings. The latter came with the 21-day suspension of play rule. While all other conferences abide by CDC regulations—10 days of non-activity for those who test positive—the Big Ten determined three weeks.

Some players aren’t fans of the policy. Last month, Michigan linebacker Josh Ross called it “outrageous.” Indiana QB Michael Penix in a recent interview said of the policy, “It’s a long time.”

Says Schapiro: “They said 21 days. I’m an economist by trade. Who am I to tell an expert, ‘Why 21 and not 20 or 10 or 14?’”

Penn State athletic director Sandy Barbour, who co-chaired the conference’s medical subcommittee, says the two things—the 21-day rule and the battery of cardiac tests—are distinctly related. League medical experts believed that in order to obtain, process and evaluate results from those tests, specifically the cardiac MRI, they needed a full three weeks before an athlete could return to play.

“We decided as a group, leaning heavily on the medical experts, to take as much risk out of this as we could,” she says. “The cardiac MRI is considered the gold standard.”

A few weeks later, some of the nation’s best sports cardiologists are saying that it isn’t needed.

For full-size image, click here

Journal of the American Medical Association

Learning about the data during an interview Wednesday with SI, Alvarez believes the conference’s medical panel should “reevaluate” the 21-day policy and the intense cardiac screening protocols. At Wisconsin, Alvarez’s medical staff has not reported finding many heart abnormalities in athletes infected with COVID since the Big Ten’s restart. “If I don’t hear anything, that means there hasn’t been much,” he says.

Barbour believes the 21-day policy could be reduced. The Big Ten is in the midst of compiling data from those cardiac MRIs that its schools are performing. “When we have enough data, we’ll take a look at that and see if the medical community wants to revise the recommendations, then the presidents and chancellors can make a decision," she says.

The Big Ten’s cardiac screening process is not the only such in the country—it’s just more stringent than all others.

Keeping with the theme of college football’s fractured nature this year, conferences have varying rules regarding post-COVID-19 cardiac screening.

The Big Ten and Big 12 operate under the most rigorous of cardiac requirements. Athletes testing positive, no matter the severity of their symptoms, are required to undergo all four screenings. But in the Big 12, the screenings are administered sooner, allowing a return to play after the standard 10-day isolation.

The SEC, ACC, Pac-12 and C-USA require only the three standard screenings (troponin blood test, EKG and echocardiogram), while a cardiac MRI is recommended only if abnormalities are found with the other three or underlying conditions warrant such a measure.

Things are different among other Group of Five leagues, which have fewer resources than their big brothers. For instance, the Sun Belt’s cardiac screening requirements are left up to the team physician on a case-by-case basis. In the Mountain West and MAC, an EKG, echocardiogram and troponin test are only recommended for those with severe symptoms. An MRI is used in extreme cases.

Meanwhile, the AAC’s cardiac protocols are almost identical to those recommended in the most recent article in JAMA. Those with moderate or severe symptoms are screened via the three standard tests, with an MRI recommended if other tests show abnormalities.

So, what’s the best protocol? The JAMA article is “the closest to the right answer right now,” says Ackerman.

Ackerman does not agree with the Big Ten’s policy to wait at least 14 days after infection to begin the cardiac screening process. Those tests could begin as early as Day 7 of the traditional 10-day isolation, he says. Or the tests might not ever need to begin, given recent data. “You could argue that if you’re asymptomatic, we don’t really need to be staring at your heart,” says Ackerman.

The Big Ten’s strict protocols and those from other leagues are rooted in the available science at the time. Even authors of the latest cardiac paper believed just two months ago that a battery of cardiac tests were needed for all of those who tested positive.

“At the time, there was a national lockdown, so we based a lot of concern and recommendation purely on opinion for what we were seeing among hospitalized patients,” says Jonathan Kim, an assistant professor of cardiology at Emory in Atlanta as well as the team cardiologist for Georgia Tech.

One of the paper’s major points is to think about the asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic athletes as “being in a different risk category than the more severely sick individuals,” says Aaron Baggish, another primary author of the paper who serves as a team cardiologist and/or physician for numerous athletic teams, including the New England Patriots and Boston Bruins.

“We’re just not seeing a lot of clinically relevant cardiovascular disease [in those athletes],” he continues while speaking on a JAMA podcast interview made available to SI. “This document, although it calls for continued data and more study, makes the case that not all COVID is created equal.”

At the center of the medical paper is the relevance and necessity—or lackthereof—for post-virus cardiac MRI, the most intrusive and expensive of the screening battery. There is “insufficient data” to support the use of cardiac MRIs to screen all athletes, according to the document. In fact, cardiac MRIs can produce what the paper terms as “false positives,” finding pre-COVID abnormalities that could potentially disqualify an athlete and have physicians scrambling over nothing.

James Udelson, the chief of the division of cardiology and director of the Nuclear Cardiology Laboratory at Tufts Medical Center, describes this as “overimaging” a patient. “Early on, there were case reports out of Italy and China of true myocarditis,” he says. “However, later autopsy reports showed that wasn’t the case.”

Jon Drezner, a team physician for the Washington Huskies and one of the most respected sports cardiac specialists in the nation, uses an analogy to describe false positive MRIs. Imagine doctors performed spinal MRIs on 100 50-year-old men who have had no back pain in their lives. About half of those men would show findings of degenerative spine disease. “So how do you interpret that?” Drezner asks.

Ackerman refers to this as “non-specific noise” from MRIs, which is the root of an Ohio State study published in August that raised alarms across college football over myocarditis. “The non-specific nature of that test starts to put more and more people unnecessarily in the penalty box for no good reason,” Ackerman says.

Cardiac MRIs aren’t easy to come by, either. In fact, Penn State’s closest cardiac MRI machine is 90 minutes away in Hershey, Barbour says.

Meanwhile, across the nation, physicians continue to find slim traces of myocarditis, as the JAMA paper notes. In Washington and in the Pac-12, for instance, Drezner says there “a lot of screening happening and not a lot of true cardiac pathology is being found.”

So what now? More data is needed.

Drezner is heading the NCAA registry of cardiac data in college athletes. At least 70 schools have agreed to participate. Data is rolling in each day. By the end of November, he expects to have enough to generate a full report. Drezner doesn’t anticipate conferences adjusting their cardiac protocols because of the JAMA paper, but those moves could come in time.

For now, the JAMA paper opens the door for entities with fewer cardiac resources—junior colleges, high schools, lower NCAA divisions—to begin playing sports, he says.

However, the long-term impacts of COVID on the heart are still unknown issues, says Martinez. Physicians won’t know those answers for another six to 12 months.

For now, Ackerman, the Mayo Clinic cardiologist, has been proven accurate in his assessment months ago. When many physicians zigged, he zagged. From the very start, as the wave of myocarditis washed across the Big Ten and other leagues, Ackerman calmed the nerves by, he says, calling “foul” on the presumption of so many medical experts as it relates to this topic. He visited with both Big 12 and C-USA officials in the days after the Big Ten and Pac-12’s decisions. Many believe his testimonial with Big 12 leaders on Aug. 11 helped convince them to move forward with a 2020 season, avoiding a domino effect that could have toppled all of college sports.

He received enough hate mail and messages that he completely stopped reading responses in his inbox and on social media.

“I provided a perspective that helped those conferences slow down the COVID-19 freight train that was heading their way and do a conference reset," Ackerman says. “Depending on a person’s perspective, I’m usually the hero or the villain that saved college football."