Catching up with Ronnie Fields

The world of YouTube can make legends out of nobodys, but in the case of Ronnie Fields, it can also keep legends alive. A collection of his high-flying dunks and soaring blocks from his high school days in the mid 90's has received almost 170,000 hits. A mural at Chicago's Farragut Academy remembers his career there.

Since his graduation from Farragut in 1995, Fields has gone from playground legend to playground warning, oft cited by players like current Bulls point guard Derrick Rose: "If we hadn't kept [bad influences] away, he could have ended up like Ronnie Fields," Rose's brother, Reggie, told SI in 2006.

In his last full season on the court, Fields averaged 21.4 points, 4.9 assists, and a league-leading 2.7 steals a game -- for the Minot (N.D.) Skyrockets of the CBA. North Dakota is not exactly where Fields, now 32, thought he would be when he was once on top of the basketball world.

As for his place as a warning in Chicago basketball lore, he said he's made peace with that. "I'm happy to see that [Rose] didn't make some of the mistakes that I made," Fields said. "It's praise to be mentioned because when people are not talking about you, then you must not be important. I've influenced people in many ways, good and bad."

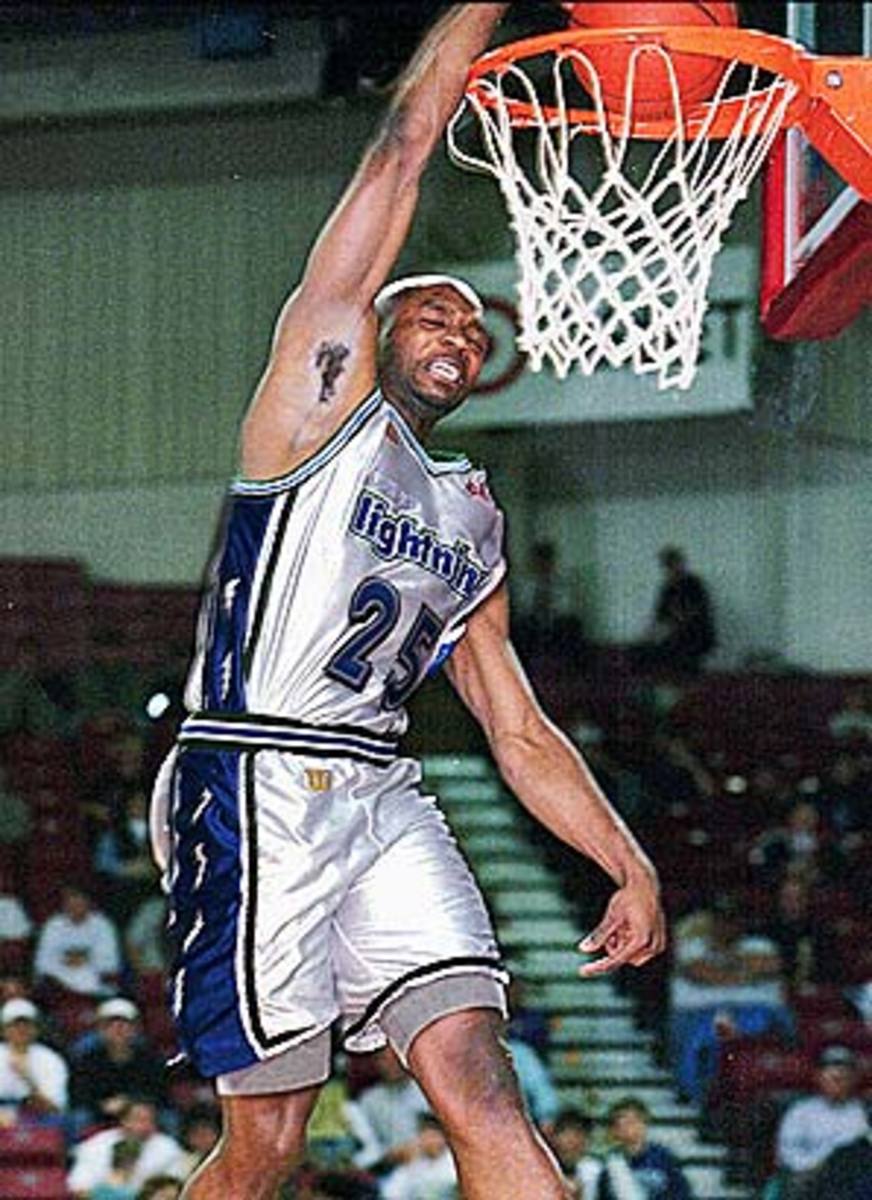

At only 6-3, Ronnie Fields' athletic abilities set him apart from the beginning of his career at Farragut, helping him earn a spot on the varsity team as a freshman. Soon after, DePaul's then-head coach Joey Meyer saw Fields as the player that could help rejuvenate the Blue Demons program. "He was a freak of nature -- he could jump out of the gym," said Meyer, now a head coach in the NBA Developmental League.

But it's the '94-'95 season that most people will always remember. Joined by Kevin Garnett at Farragut, the two dominated the basketball landscape in Chicago and advanced to the state quarterfinals. "They were like the Beatles in Chicago," recalled Chicago basketball analyst Dave Kaplan.

When Garnett left for the NBA in 1995, Fields was left to lead the team for his senior year. The squad went 11-1 in the Chicago Public League and Fields averaged an absurd 32.4 points, 12.2 rebounds, 5.1 assists, 4.5 blocks, 4 steals, and 4.5 dunks a game. Those numbers put him on the All-American team with current-NBA players Mike Bibby, Jermaine O'Neal, Tim Thomas, and Kobe Bryant -- the player he jockeyed with for the honor of top high school star in the nation.

That would be as heralded and popular as Fields' career would ever be. He was in a life-threatening car accident one week before the city playoffs. Doctors performed surgery to repair a fractured bone in his neck, forcing Fields to appear at his team's playoff game in a halo, not a uniform.

"I could have been dead, or paralyzed for the rest of my life," said Fields. "All I wanted to know was if I could just go play basketball."

Fields -- who played in tournaments after the accident without his doctor's permission -- says that setback should have been his wake-up call, but things continued to get worse.

Fields was to attend to DePaul, spend a year getting his grades up, and receive a need-based basketball scholarship. But in July, DePaul called Fields with the news that his test scores and grades weren't up to par and his scholarship was soon rescinded. A few months later, Fields pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of sexual abuse.

In the span of five months, Fields went from looking at a multi-million dollar contract in the NBA to disappearing from the basketball landscape. Thirteen years later, Fields has had plenty of time to reflect on his regrets and he is most disappointed about losing the opportunity to get an education.

"I want people to know this: There's a lot more in life than going to play a professional sport. It's about growing up to be a human being, a good person, and being an educated person," Fields said.

After a brief stint playing professionally in Greece, Fields returned to the States, where he had success in the ABA and CBA. One of his ABA stops was in familiar territory with a familiar coach as he reunited with Meyer in the 2000-2001 season with the Chicago Skyliners.

"A lot of guys have egos, but Ronnie never let an ego get in the way of his game, and he wanted to win," said Meyer.

Fields spent the last few seasons in Minot before the league folded in February. His illustrious CBA career includes back-to-back scoring championships, over 6,000 career points, and he ranks sixth all-time in career points. But far from the quick-talking Chicago star he once was, Fields shows his humility when asked about his greatest basketball accomplishment.

"Being able to grow from just a scoring leader to leading a team to the championship this past season [in Minot]," he said. "Just knowing what it takes to be a leader and what I've learned to get there is incredible."

Fields is spending his extended off-season in Lombard, Ill. with his girlfriend of six years, Jennifer, and also spends time with his 11-year-old daughter, Lisa Ann.

"My daughter is so smart and talented," he said. When asked if Lisa Ann has her father's knack for basketball, Fields wavers from his low, soft-spoken voice and finally laughs. "She likes to play sports because it's a little bit in her blood from me, but she has other loves. She's seen tapes of what her Daddy has done, and knows what her father has been through -- that makes me happy more than anything."

Fields' agent, Keith Kreiter, said Fields would like to conclude his career in Western Europe, and then go into coaching. "He is still a high flyer and knows the game real well. Everyone feels that he is a winner," said Kreiter. "He has a great feel for the game, and he would make a great coach."

Fields' playing career only has a few years left. While he may always be known as the story of 'what could have been,' Fields and those who know him best will tell you that he has made his life a success story in its own right.

"What impressed me was he kept at it and didn't let his life fall apart," said Meyer. "He won't get the great publicity because he never became the great star. He didn't fall apart and get into drugs -- he hung in there and kept playing."

Fields is accustomed to the fashion in which his name is uttered these days. He knows the legacy people remember him for, but Fields never wavered from his ultimate mantra on life -- reinforcing that while he understands how good he was and what he could have been, he is extremely proud of the path he took.

"People can't say 'This kid dropped out and hung on the street corner and gave up on life,'" Fields said. "I pushed through the situation. I owned up to the things I did and became a better person, player, and father -- those things are more important to me than playing professional basketball."