Following tragedy, Comer leading Florida Gulf Coast to new heights

PHILADELPHIA -- With 30 seconds remaining in Florida Gulf Coast's upset of Georgetown in the NCAA Tournament, guard Brett Comer looked around the arena and soaked in the extreme emotional contrasts.

The cheers of nearly 20,000 fans washed down from the crowd, the relentless euphoria of a momentous NCAA upset. Amid the chaos, Comer locked eyes with his mother, Heather, in the eighth row of section 114.

"We didn't have to say anything," Heather Comer said by phone on Saturday. "All we do is look at each other. We're both thinking of his dad."

Florida Gulf Coast's upset of Georgetown on Friday night had everything -- drama, history and a signature moment. When Comer flipped an alley-oop to teammate Chase Fieler for a one-handed tomahawk that sealed the game, the players immediately etched themselves in NCAA lore.

But when Comer looked into the stands and let the roar of the crowd reverberate through him, he knew the game with everything was missing one thing.

More than three years ago, Troy Comer died from lung cancer.

He'd coached Brett in AAU, built a court behind their house and spent countless hours rebounding while his son hoisted jump shots.

"It's kind of weird without my dad," Comer said. "I know he would have loved to be part of this."

In Troy Comer's obituary in the Orlando Sentinel, Brett is described as his "best friend." In the year after his diagnosis, Troy Comer spiraled so fast that he couldn't drive a car, couldn't leave bed and eventually couldn't talk. All he could do was moan, as the tumors grew so fast that every movement caused discomfort. Heather Comer said her husband, who was 46, looked "90 years old" at the time of his death.

"I feel like it literally killed me," Brett said. "That's stuff I'll never be able to forget for the rest of my life."

His father's death haunted Brett. He struggled with anxiety, mood swings and occasional fits of depression.

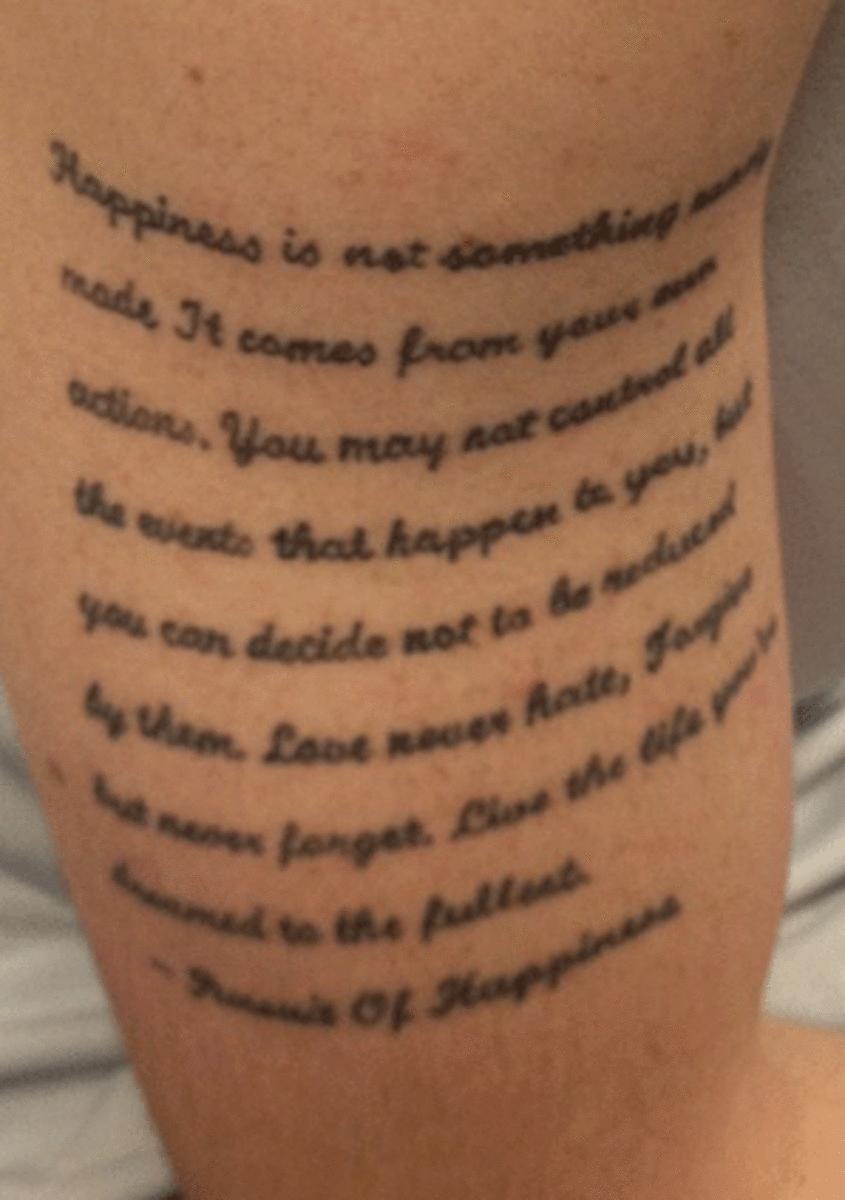

In the fall, he met with FGCU coach Andy Enfield and his mother and they all agreed he should see someone. Comer began meeting weekly with a grief counselor and the changes were drastic. By late November, after a game against St. John's, he began feeling normal. He got a pair of tattoos to honor his father, one of which he touches before every game.

"I got to the point where I could really be myself again," he said. "I wanted to keep it in. I didn't want to talk to anyone about it."

FGCU assistant Kevin Norris, a former star point guard at Miami, became a sounding board. Norris lost his father in high school as well. Comer got to the point where he felt comfortable sharing things with Norris and a few teammates, such as talking about the anniversary of his father's death or missing him at big games. Instead of being withdrawn, Comer opened up.

"My dad died in 1991, and it feels like it was yesterday," Norris said. "Me and my dad was close, too. I tell him, 'He's up there and proud of everything you are doing. The better you are, the more that he's smiling at you.'"

Comer, an only child, always had a strong support system. In high school, he played in the same backcourt at Winter Park High School in the Orlando area with Austin Rivers, the son of Celtics coach Doc Rivers. They'd played together since they were small, winning an AAU Championship at age 10.

After Troy passed, Doc's wife, Kris Rivers, was among the first people to show up at Heather Comer's house to bring plates of food and hugs of support. The Rivers family hosted the Comers over for Thanksgiving that year.

"They were really good to us," Heather Comer said. "Doc's wife is awesome. She does so much for everyone and a lot of kids. They're a neat family and did take us in."

Doc Rivers told reporters on Saturday night that it was "awesome" that Florida Gulf Coast won. "It's really nice," Rivers said. "Just a huge place in my heart."

The day that Troy Comer passed, Brett Comer elected to play a game against rival Dr. Phillips High School, who featured star guard Shane Larkin. The entire Winter Park team wrote "RIP Mr. Comer" and "TC" on their sneakers. Brett scored a team-high 16 points after Austin Rivers fouled out with more than 10 minutes left. Winter Park won 66-65.

"You could feel it in the gym that night," Heather Comer said. "It was really a great night. Every time Brett scored and the whole place went crazy."

The feeling emerged in Philadelphia on Friday night with nearly two minutes remaining. With Otto Porter chasing him down, Comer darted toward the basket and threw a one-handed flip over his shoulder to a streaking Fieler, who tomahawked the ball and basketball convention. After Georgetown cut a 19-point lead to seven, FGCU ran a play from the AND1 Mixtape tour instead of running out the clock. Even better, they acted after like it wasn't a big deal.

"People were making fun of the lob pass, like how free he plays, and I was thinking you don't know Brett Comer the way we know Brett Comer," Doc Rivers said. He added that Austin and Brett won back-to-back state titles and averaged nearly 90 points in a 32-minute game. "He's played that freely his whole life," Rivers said.

Florida Gulf Coast faces San Diego State on Sunday night, another chance for the Eagles to ambush history and turn Philadelphia into Lob City for a long weekend. They couldn't have reached this point without Comer, a guard so talented that Enfield said he's the most creative he's ever seen, a high compliment considering Enfield coached in the NBA and ACC.

Comer couldn't have gotten to this point without having his dad to help, and then having help to deal with his dad's loss. Instead of anxiety and stress, Comer has become the poster child for playing free and easy. And in one pass, Comer got a chance to tell the world how much his father's assists meant to him over the years.

"The best part of all this is that Brett is having the change to honor his dad," Heather Comer said. "And that Troy is being remembered."