UCC Strong: After deadliest shooting in Oregon history, Umpqua women's basketball honors victims

ROSEBURG, Ore. — Jasmyne Davis's mind raced the morning of Oct. 1, 2015, when the point guard for the Umpqua women's basketball team heard a familiar sound as she sat in Room 16 of Snyder Hall, clicking away on a computer during Writing 122.

Pop!

Was that a gun shot next door?

Pop! Pop! POP!

Those are gun shots. Who's shooting? I left south central L.A.to get away from this—is this really following me? What if he comes in here next?

Silence, then a spray of fire. Davis, 20, reached for her phone and dialed her mother in Los Angeles. No answer.

Across campus, Riverhawks women's basketball coach Dave Stricklin sat in his office comforting Ashley Backen, a freshman forward who had just learned she would miss the 2015–16 season with a torn right ACL. Neither knew of the horror unfolding 200 yards away until Stricklin's phone buzzed. Stricklin, 57, typically does not answer his phone in meetings. The exception is when one of his players calls. A father of four, Stricklin wants his players to "feel like they've joined a family, not a team," and prides himself on being available 24/7.

On the other end of the line, a panicked Davis spit out a flurry of information. "Coach Dave, there's a shooter," he remembers her saying. "I'm going to die. Kim was shot, she's bleeding everywhere, we're doing CPR, it's not working. I'm going to die."

Stricklin, who has been a health instructor and coach for 21 years at Umpqua, reacted instinctively.

"I coached her," he says. "It's like during a game. If we're being pressed and turning the ball over and I'm starting to worry and my stomach's getting upset and going crazy, I can't tell her any of that. Players have to think you're calm, or they'll panic, too. So I talked to her in a regular voice, told her to get low, make smart decisions, and stay on the phone with me."

A shooter killed nine people in fewer than 10 minutes at Umpqua Community College that day, injuring seven others, and then shooting himself. Five months later Roseburg, a town of 22,000, is still trying to move on from Oregon's deadliest shooting.

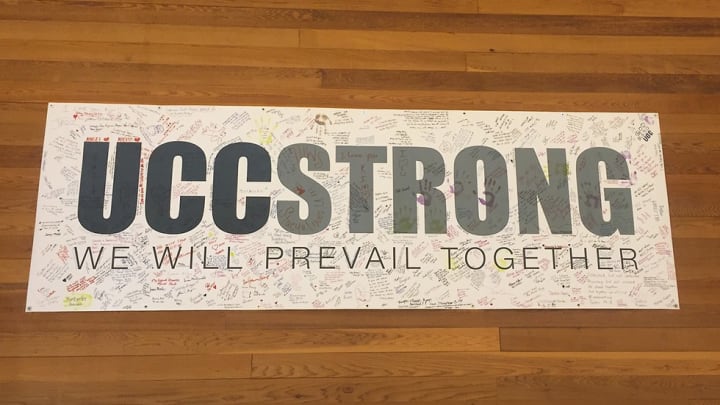

Players for Umpqua, one of the top women's junior college teams in the Northwest, didn't want their season to become a tour of candlelight vigils or repeated moments of silence. UCC players wanted a quiet, everyday reminder of who they're playing for this season.

Davis came up with the idea. There are nine active UCC players this season, and nine victims, and Davis couldn't stop thinking about Kim Deitz, a 59-year-old student who Davis says gave off "a mom kind of vibe." In Room 16 that day, as terrified students huddled in the corner, Deitz ran outside to close the door. She was shot three times, pulling the door shut as she staggered into the classroom, blood streaking the wall where she fell. Davis says Deitz saved her, and everyone else in Room 16. So every game day, Davis pulls on a long-sleeved black shirt with "UCC Strong" on the front—a phrase that made social media rounds in the hours and days following the shooting, and the words Umpqua players break each huddle with—and "Deitz" on the back. Each of Umpqua's nine players honors the name of a victim on her warmup jersey.

Thursday, Umpqua starts its journey through the Northwest Athletic Conference championship tournament. The team hopes to provide a distraction during a school year full of sorrow. There's an opportunity, says sophomore forward Anna Mumm, to bring "a championship, and maybe some happiness" back to a distraught community. "For the first time in my career," says Stricklin, who has coached more than 30 years, "I'm telling them to play for the name on the back instead of the name on the front."

*****

Courtesy UCC Athletics

When Davis later recounted the shooting to her friends back in L.A.—the sound of bullets, the police officers bursting into the classroom, the 200-yard sprint to Stricklin's office and into his arms—they didn't get it. Why would Davis, a black woman from the inner city, call Stricklin, a middle-aged white guy, as her world unraveled?

"I knew he would be there," she told them.

Stricklin arrived at UCC in 1995, after eight years at Golden West College in Huntington Beach, Calif., where he won two California junior college state titles and averaged 32 wins a season. During his 21 years in Roseburg, Umpqua has had a reputation in the NWAC of recruiting big, bruising girls who play with grittiness. Stricklin, who is assisted by his 80-year-old father, Richard, is influenced partially by the late and legendary Jerry Tarkanian, who built a powerhouse at UNLV by taking "kids from the margins, guys who were overlooked or edgy, kids other [coaches] were scared of," Dave Stricklin says.

Dave's wife, Linda, says her husband has often recruited kids "who are from rough areas, but aren't really rough themselves—they're looking for a way out." She's had a front row seat to Dave's coaching philosophy, as she was a forward for him at UCC from 1996–97 to 1997–98. Linda and Dave were married shortly after Linda's eligibility expired and have been together for 17 years. (The couple says they never dated while Linda was on the team and contend that their relationship was never an issue with the school.)

Dave has stayed at UCC despite offers from other Division II and III schools because he believes junior colleges are where he can make the biggest impact. In 32 years of juco coaching, he's sent 109 women on to four-year schools.

Romanalyn "Mana" Inocencio played the past two seasons for Stricklin at UCC, then got a scholarship offer to finish her college career at Division-I University of Maine-Fort Kent. An Oakland, Calif., native, Inocencio spent her winter break visiting her former teammates in Albany, Ore., where they were playing a holiday tournament, opting to skip seeing her actual family to hang with her adopted one instead.

"He takes us to the store, answers our calls, treats us like one of his own kids. He keeps his word and for a lot of us, that's important and rare," Inocencio says. "Where a lot of us are from, people leave us hanging."

Inocenio is reminded constantly of why she left Oakland. On Dec. 20, the day she visited her old teammates, she got a phone call that her uncle had been shot and killed—the victim of a drive-by shooting—early that morning, just 25 miles from her hometown.

"A lot of us [that come to play at Umpqua], we're just trying to escape poverty, guns, that type of stuff," she says. "And Dave, he listens first. Instead of saying, 'I understand,' he says 'I'm here if you need me.'"

In more than three decades of coaching, Stricklin has dealt with almost everything: eating disorders, run-ins with the police, bad breakups and jealous exes. But he had never coached his kids through a mass shooting.

In his office at UCC, Stricklin's shelves are packed with coaching books, VHS tapes and DVDs. "None of them tell you how to deal with tragedy," he says. "[Our] school said all the athletes had to go to mandatory grief counseling, but who decided that? I wish someone, some coach, could have called me and said, 'This is what we did when it happened here.'"

Stricklin is convinced now that college coaches can and should have open dialoge about dealing with tragedy. Though a mass shooting was new to Stricklin, murder was not, as he told his team the night of the shooting, when they gathered at assistant coach Perry Murray's home. Linda read Facebook messages from former UCC players expressing their shock and support, and coaches talked about "tightening the circle" in the coming days.

Then Stricklin shared the story of Krisden Tanabe.

*****

Photo: Mike Sullivan

A freshman at Golden West in 1989, Tanabe was on her way home from practice with her teammate, Donna Gondringer, when they stopped at Gondringer's house. Thomas White, Tanabe's ex-boyfriend, was waiting for her there. After assuring Gondringer she would be fine by herself, Tanabe again told White again that they were no longer a couple; they had broken up four months prior, though White did not take the news well according to family members who spoke with reporters. When she turned to walk away, he shot her in the back of the neck. Gondringer rushed outside at the sound, just in time to see White point the gun at himself and pull the trigger.

Stricklin heard of the news that night at home, when a Los Angeles Times reporter called and asked if he wanted to comment on the murder-suicide.

The day after Tanabe's murder, Stricklin's players wanted to be in the gym. Stricklin recalls a heated practice. "The girls were pissed, they were physical," he says. "They went after each other trying to work out that anger."

For the remainder of the 1989–90 season, whenever Golden West won a trophy, someone would take it to the cemetery and set it on Tanabe's grave. They went 37–1 that year, winning the California state championship. Her name, Stricklin says, was never mentioned. It didn't need to be. "We knew who we were playing for." Twenty-seven years after her death, Stricklin keeps the program from Tanabe's funeral tucked into a book about 2-3

zone offense that he re-reads each season.

Stricklin tried to apply the same principles in this tragedy. At the team's request, UCC practiced the next day, at Sutherlin High , seven miles outside Roseburg. "Campus was closed and there was so much commotion in town," Stricklin says. "Right after it happened, you couldn't get away from it. There were as many grief counselors here as students. Everyone was like, 'Are you O.K.? Do you want to talk? Do you want to pet this therapy dog?' All I could think was, 'We've got to go have some fun."

Stricklin called Oregon coach Kelly Graves and arranged a "behind the scenes, good tour" of the Ducks' sparkling facilities in Eugene, lauded as some of the best, and fanciest, in collegiate sports. But three days after the shooting, UCC administrators canceled the field trip, saying all team activities were banned until further notice. Meanwhile, campus was closed for the week, and classes didn't resume until Oct. 12. Administrators told coaches they wanted athletes to "have time to grieve and deal with what's going on without any added pressure or responsibilities." Stricklin balked.

"Part of me was insulted," he says. "They insinuated I was doing something self-serving. I mean, I know these girls, not these players, but these people, better than anyone—and now you're going to tell me how to deal with my family?"

Stricklin's hope and goal as a coach is the same as a parent: That eventually, your kids can thrive without you. He sees strides in that direction. After players were told of the "no team activities" mandate from administrators, they organized their own, players-only practice, with sophomores running drills and scrimmages.

*****

Photo: Mike Sullivan

Freshman guard Syd Clark had the same nightmare for weeks: She's in Room 16 with Davis when the shooter walks and starts firing. The shooter points the gun at Clark's head and she wakes up.

Though she wasn't on campus the morning of Oct. 1—she decided she was too tired to work out—Clark is haunted by what could have been. She wonders if a part of her knew it was coming. The night before the shooting, as she chatted on the phone with a friend, she had an eerie adrenaline rush. Suddenly, she says, "I didn't feel safe." A freshman from Las Vegas, Clark brushed it aside, figuring she'd been in Roseburg only two weeks, and just wasn't used to being alone. Within hours of the massacre, she found out she lived in the same apartment complex, just three buildings down, as the shooter. She went home to Vegas for a week, but returned to UCC because "I knew, this is my family."

Mumm, the sophomore forward, had troubles, too. She wears the name Anspatch on her warmup shirt, in memory of her friend and former men's basketball player Treven Anspatch, who laid on top of a girl while bleeding out, and told her to play dead, possibly saving her life. Anspatch was a Sutherlin High graduate and when the UCC women went to Sutherlin the day after the shooting, Mumm had a panic attack. Ninety minutes into practice her body started tingling. Overcome with fear, she couldn't breathe or talk. Hyperventilating and shaking, she ran out of the gym.

One player, a freshman from California, left after the shooting and didn't come back to campus. UCC played for a stretch in December with just seven healthy players.

Other players have had smaller moments of adjustment. In their first few weeks back on campus, players asked Stricklin to lock the gym doors during practice to help calm their nerves. Sawyer Klunge, a sophomore guard from Bremerton, Wash., used to sleep with her apartment's front door unlocked. Now, she locks the door whenever she's inside. She wears the name of Lawrence Levine, the writing instructor who was killed first. Klunge still calls him "my favorite teacher."

Shaunta Jackson, a freshman forward from Beaverton, Ore., showed up in Stricklin's office minutes after Davis' call alerted him—and campus—to the shooting. Hysterical, she sobbed about Davis being in the same building as the gunman. Still shaken months later, Jackson stops by each day, saying she's on the hunt for popcorn or soup or gossip, sometimes toting a slice of cake or cookies and offering it to Stricklin. Really, she's just checking to make sure everyone is where they're supposed to be.

Everywhere they go, people want to talk about it. At a Wendy's in Portland on their way home from a Jan. 9 game at Portland Community College, an instructor from PCC introduced himself and asked about Oct. 1. When Stricklin calls to make hotel reservations, front desk clerks often ask why they know the name Umpqua. When he tells them, they murmur sympathetically. Clark says when they lose—a rare occurrence this season, as the Riverhawks are 24–6—she gets frustrated by the pitying looks from fans, most of whom seem to be thinking, Gosh they've already been through so much.

It gets old, being the team everyone feels sorry for. But the girls say for as awful as that day was, it's helpful to feel part of something bigger. Multiple opponents have done something to show support for Umpqua this season, from hanging a "UCC Strong" banner in the gym to hosting a student body "green out," (that's Umpqua's school color) to printing their own "UCC Strong" shirts and wearing them during warmups.

"When something awful happens, you see the humanity in people," says Jim Martineau, who graduated from Sutherlin High and is as connected to Roseburg as anyone in the NWAC. He's been the Clackamas CC head coach for the past 18 years, and is close with Stricklin. "After the shooting, so many teams did something for Umpqua. That community, that support, it's unique—it's what makes women's basketball so special."

*****

CourtesyUCC Athletics

Many fans still don't know about UCC's tribute because players and coaches haven't given any explicit explanation. At Umpqua's last regular season game Feb. 27, some fans in their own arena asked one another why every player had the No. 9 on her back. Stricklin thought about saying something to the crowd but decided against it. In some ways, the town is still in the beginning stages of healing; just two days before, the last surviving victim had left the hospital. Occasionally he'll say something in team-only settings, when he'll remind his players that they can honor the victims by how they conduct themselves on and off the court.

They still have questions. When Mumm walks past the poster of Anspatch outside the Umpqua gym, she's flooded with sadness. Why him? Why us? Clark wears the name Cooper in memory of Quinn Cooper, a freshman who grew up in Roseburg. She doesn't know much, if anything, about him, and admits she's scared to ask, for fear of guilt. What if I find out about him and then I think, Why him and not me? Stricklin wonders if he'll ever have to deal with something this gutting again. Backen, the freshman with the torn ACL, asks if it's weird that she actually feels safe at UCC now, because statistically, the odds are in her favor that it won't happen again.

The team takes its cue from Davis. She hasn't cried once since the shooting, and still plays with a fearless, breakneck speed, cursing under her breath when she misses a shot or throws the ball away. "Jas being so strong helped everybody," Stricklin says. "We forget, she watched people die that day." Davis says the shooting did not soften or harden her; after all, she's sort of used to this stuff.

Teammates say there are small differences, though. Davis says "I love you," more now, and she always greets Stricklin's 16-year-old daughter, the unofficial little sister of the team, with a long, hard hug. She feels pride, not sadness, every time she pulls on her warmup shirt with Dietz's name. "She sacrificed for us, she's a hero," Davis says. "I'm blessed to have her name on my back." Still, Davis has questions, too.

How could this happen here?

Is anywhere safe?

Is this ever going to stop?

And then, always, If we win a championship, will people remember us for that instead?