Destiny Denied: Phillies’ Cinderella Run Falls Short of the Finish Line

HOUSTON — The Astros popped champagne. The Phillies forlornly popped open some beers, down the hall yet a world away, a clubhouse’s worth of sad Coors Light and Bud Heavy. After a month punctuated by the kind of alcohol consumption that requires safety goggles and protective coverings, the roster suddenly had to get reacquainted with drinks meant for consolation rather than celebration.

They had fallen 4–1 to the Astros in Game 6 of the World Series—a third consecutive loss. A series that once looked very much in their control had slipped all the way out of it. The result was a specific kind of baseball pain unfamiliar to most of the room: The Phillies had snapped an 11-season postseason drought to get here and then, suddenly, in the last berth created by a newly expanded playoff structure, they’d made it all the way to the World Series. The experience had been a whirlwind. And it made the final loss especially hard to process. This group was largely familiar with September collapses, with terrible blowouts, with seasons that never really got off the ground in the first place. Some of their more recent additions were even familiar with how it felt to win it all. But to lose it all?

This was miserably new.

Or as put by Aaron Nola, the longest tenured member of this roster, the only player still here from when the franchise bottomed out in 2015:

“It sucks,” the pitcher said. “It stings. But what a heck of a run. ... Nobody expected us to be here except us.”

They had pulled off some of the biggest comebacks in recent playoff history. They’d provided a month’s worth of weird, enchanting, unexpected moments. They had done it all as a team that won just 87 games in the regular season and fired its manager in June. And now the ride was over.

“It’s tough,” said first baseman Rhys Hoskins. “There’s a lot of competitors in here, a lot of people who obviously put in a lot of work to be here. But I think we should be proud of where we landed.”

The clock struck midnight on the Phillies’ Cinderella run on the night clocks fall backward.

David J. Phillip/AP

That big-picture view seemed clear enough. But in the immediate aftermath, there were plenty of finer points open to continued, torturous fixation.

There was the offense’s performance with runners on: The Phillies were 1-for-20 with runners in scoring position across the last five games of this series. (Incredibly, that includes their 7–0 victory in Game 3, where they were 0-for-3 with RISP—all their scoring that night came via home runs with the bases empty or a runner only at first.) On Saturday, they barely gave themselves a chance to improve that record, putting a runner in scoring position only once: In the second inning, Alec Bohm had singled, and Matt Vierling had moved him over by drawing a walk. But the next hitter, Edmundo Sosa, flew out to the deepest part of the ballpark. He’d missed a home run by only a few feet. Yet the scorecard held only a “F7” to show for it, and for the rest of the night, Philadelphia would not come to the plate with a runner in scoring position. That’s a credit to the Astros’ pitching—among the best in baseball this year for a reason—but it’s a frustrating question, too, for a Phillies offense designed to slug.

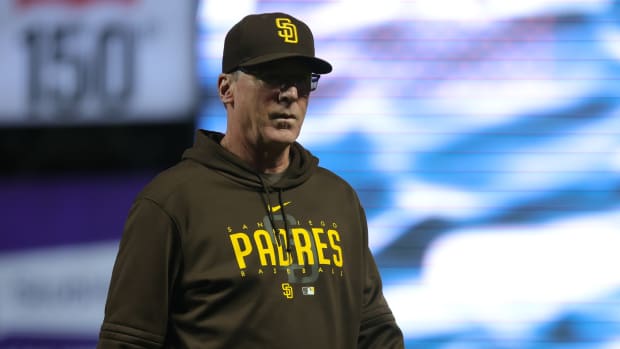

“I think it was a combination of a couple things, really,” Philadelphia manager Rob Thomson said. “Just that we went through a dry spell at the wrong time. And you got to give credit to their pitching. … They got a really good ball club and they can beat you in a lot of different ways.”

But there was also Thomson’s decision to pull starter Zack Wheeler in the sixth inning for José Alvarado to face Houston slugger Yordan Alvarez. There were runners at the corners with one out—the first real jam the starting pitcher had gotten in—and the Phillies were clinging to a 1–0 lead after a solo home run from Kyle Schwarber. On paper, certainly, Alvarado for Alvarez seemed like a smart matchup. But Wheeler—who’d been given an extra two days’ rest by starting in Game 6 rather than Game 5—appeared to still have his best stuff. He was at only 70 pitches; his velocity hadn’t flagged, and, while he was going through the order for a third time, he’d had no trouble before with Alvarez. Wheeler said he was caught a bit off guard by Thomson coming to get him.

He watched from the dugout as Alvarado gave up the game-winning home run.

Would he have preferred a chance to get out of the jam himself?

“Yeah,” Wheeler said. “I would have. It was win or go home right there, and it’s a tough pill to swallow. Ultimately, it’s Thoms’s call, and that’s the call he made. … It is what it is.”

A little more than an hour later, it was all over. The Phillies were left to look on from a quiet dugout as the Astros celebrated on the field.

“That’ll stay with us,” Hoskins said. “Until we get [back] there.”

That image feels indelible. But so many other, happier ones from this month do, too. Asked what he would remember most about this run—his first time in the playoffs in his eight seasons with the team—Nola flipped through a few, the comebacks, the surprises, the big home runs. He settled on something more amorphous: He’d remember how it felt in the clubhouse. Because it had never felt like this for him before.

“Nobody ever got down on each other. Nobody ever got down on themselves,” Nola said. “I think that was the biggest thing for me, and I think it rubbed off on everybody on this club. … We were just all pulling on the same rope the whole time.”

The clubhouse whiteboard that would have shared tomorrow’s schedule was conspicuously empty: No time listed for batting practice or pitchers’ stretch. But someone had left a message scrawled in marker that held either way: “Clocks fall back 1 hour tonight.” The end of daylight savings time could have meant an extra hour for the Phillies to sleep and prepare for a Game 7. Instead, there was nothing on the schedule. All that was left for them to do was sit down and share one last quiet beer.

More MLB Coverage:

• The Astros Are World Series Champions—No Asterisk Needed

• The Batting Cage Session That Won the Astros the World Series

• Verlander Completes Epic Comeback Year With First World Series Win

• Trey Mancini Saves the Astros With His Glove as His Impact Bat Fails Him

• Cristian Javier Rides His ‘Invisi-Ball’ to a Storybook World Series Win