The Final Reveal of Michael Jordan

Two months into the season, Michael Jordan looked bad. This is not to say he had looked bad for the whole of his first 26 games with the Wizards; that was a matter of some debate. The numbers were forgiving from some angles (23 points, six rebounds and five assists a night) and harsher from others (a shooting percentage that nudged just up above 40). The Wizards, who had set playoff qualification as a reasonable benchmark of comeback-season success, sat at a shaky 14–13. But on the night of Dec. 27, 2001, things reached a nadir no measure of nuance could rescue. In a blowout loss to the Indiana Pacers, the 38-year-old Jordan was sweatlogged and slow, hobbled by the pain of recent operations to drain fluid from his knee and not yet buoyed by their effects. He clanked eight of his 10 shots, and, in the third quarter, coach Doug Collins let the best player in the history of the game strap on the ice packs. Jordan finished with six points, then the fewest of his career.

During his years with the Bulls, when precious little criticism materialized and still less reached his ears, Jordan nevertheless honed a remarkable talent for unearthing it. Now there was no need; columns and SportsCenter segments scanned as obituaries. “Those bad games were his new Calbert Cheaneys,” Steve Wyche, then the Wizards beat writer for The Washington Post, says, referring to the Washington Bullets swingman whose physical style Jordan occasionally saw as an affront in the 1990s and who drew some of his most focused and explosive outings. “You could see it in warmups [of the next games]: ‘He’s lathered up, he’s not playing around today.’”

Two nights after the Pacers debacle, Washington hosted the Hornets. Less than a minute into the game, Jordan opened the Wizards’ scoring with a fadeaway jumper from the right elbow. Thirty seconds later, another. Old rhythms sounded. Faking another fade, he pivoted and ducked under his defender’s armpit to bank a four-footer off the glass. Tracking a teammate’s missed shot, Jordan slipped into the lane to tap the ball back over the front rim. He didn’t quite recapture his former ways of moving—the Air Jordan XVIIs just didn’t get as far off the floor as the XIVs had—but he was attuned to the degrees of momentum and stillness that great scorers prey on. When his opponent gave him an inch too much space, he put the jumper over top; when someone lurched out, he dropped his shoulder and powered past. He scored Washington’s first 13 points and 34 of its first-half total of 56. The Wizards won big in the end, but nobody cared; Jordan had scored 51. Steve Martin, Charlotte’s play-by-play TV announcer, laid out the game’s real purpose in the second quarter: “Relive the memories, folks.”

“Scoring six points, my career low, I’m pretty sure you guys were saying how old I was,” Jordan said afterward to the once-fawning press corps that had become, in his mind, a kind of nagging monitor. “After tonight, I’m pretty sure people are going to say I can still play this game.”

That Saturday night showed Jordan near his peak in more ways than one. As he regained his on-court prowess, he tapped into his talent for shaping the story it told. Jordan had always been one of sports’ great mythmakers: in the fusion of underdog and deity that framed his Gatorade and Nike ads; in the too-perfect hero’s journey beats of his arrival, ascent, departure from and return to Chicago; in the horizon-scanning that would let him lord over a shoe empire and unveil The Last Dance. With the Wizards, he once again cast himself, this time as the sage elder who could still go it alone when needed. “I may not have 50 points the next game,” he said, “so someone has to come in and take some of that load.”

Twenty years later, though, Jordan’s Wizards chapter remains noteworthy—singular, really, in the polish of the rest of his career—for his inability to control it. Over two losing seasons, he put up a handful of remarkable performances and as many wretched ones. He scored well but inefficiently. He set goals, failed at them, revised them. He was a genius, a has-been, a grump, a teacher and an ambassador. He added to his story as he detracted from it. If Jordan has always taken pains to tell the public who he is, here he made the clarifying mistake of showing us. To acolytes, it’s a chapter best forgotten. To anyone interested in the mechanics of greatness, and in what you can glean from those mechanics breaking down, it’s essential.

Jordan’s announcement in late September 2001 that he’d be returning to NBA floors came as no surprise. There’d been the noticeable slimming down, the vortex of rumor and nondenial, the pickup games arranged with once and current NBAers. More telling than anything, there’d been the grumbling, the acknowledged itch. “Nothin’ compares to bein’ it,” Jordan had told Post reporter Michael Leahy—the eventual author of When Nothing Else Matters, a survey of his last playing years—in December 2000. At the time, he had not been it—a player—but rather a part-owner and executive for the Wizards, a position as artificial and removed as politics to a career soldier. He’d kept a distance from the club, rarely traveling on road trips, indulging long days of golf and nights of gambling. When Leahy reminded Jordan that the Wizards had a game that night, he snapped, “I don’t.”

His process for returning had seen him lock back into his old focus. Jordan had reenlisted his personal trainer, Tim Grover, who built a regimen for strengthening the muscles around his knee. The pickup sessions served to test the soundness of the old catalog. (In one of these, a young Metta Sandiford-Artest, then Ron Artest, swung an elbow into Jordan’s abdomen, cracking a couple ribs.) He couldn’t glide through the air like he had, but he found that he could still stagger defenders with his pivot foot, which won him pockets of space for the jumper or the drive. His trash talk took the stay-in-school shape of a wizened veteran’s. “He got to jawing. It was unbelievable,” says Brian Scalabrine, a draft prospect out of USC who had worked Jordan’s summer camps during the hiatus years and partook of the heated closed-door runs afterward. “He turned into a different guy. But you could tell, in his mind, every day he was searching for a strategy, for what was gonna work that particular day.”

For those who stood to benefit from Jordan’s return, the calculus was simpler. During the 2000–01 season, the young Wizards had floundered to a 19–63 record, the third-worst in the NBA, and drew the 12th-fewest fans in the league. (“He made a coaching hire, Leonard Hamilton, and that did not work out at all,” Wyche remembers of Jordan’s first splashy executive decision. “He was on nobody’s radar.”) TV ratings had suffered since Jordan retired from the Bulls in 1998, with a labor dispute condensing the ’99 season and NBA brass fretting over the marketability of a new generation of stars. The Sept. 11 attacks cast a pall over the sports world, turning routine events into security-laden shows of resolve. “The gold standard was really Jordan, in terms of what a player should be, how he should conduct himself, his competitiveness,” remembers Stu Jackson, then an executive in the league office. “I mean, he was the guy.”

Jordan was to be a palliative, if not a savior. The Wizards had sold out their season tickets on the strength of rumor alone; the NBA tore up its national TV schedule and shoved Washington into prime-time slots. Abe Pollin, the Wizards’ principal owner, basked in the celebrity (and, to be sure, the cost: Jordan took a veteran’s minimum contract and donated the sum of it to 9/11 charities). “To have the greatest basketball player that ever played playing on my team,” he said. “With all the tragedies that have befallen our country the last couple weeks and the mood being what it is, a little good news like this is really a good thing.”

Jordan, for his part, characterized his last comeback as a project of encouragement, not dominance. What could he offer that no other executive in the league could? His presence. “There is no better way of teaching young players than to be on the court with them as a fellow player, not just in practice, but in NBA games,” he said in a reintroductory statement. Still, Collins—Jordan’s second coaching hire, handpicked for his on-court return—stoked the nostalgist’s hopes: “Michael Jordan will be one of the top 10 players in the league.”

One night in late November 2001, Jordan boarded the Wizards’ team plane from the rear, where the team’s announcers and beat reporters sat. The Wizards had just lost to the Cavaliers by 19; Jordan had led Washington with 18 points on 9-of-24 shooting. He cast his eyes down the aisle, to where his teammates settled into their seats. “F—- those mother—----,” Buckhantz remembers Jordan saying. “I’m gonna sit back here with the grownups.”

A month into the season, the Wizards had lost 10 of 13 games, and MJ the mentor was faring about as well as MJ the exec had. A roster made mostly of youthful promise and mid-career flotsam was prone to lapses in focus—after the Cavs loss, Collins had complained that they hadn’t made it out to warmups in a timely manner—and lacked the talent to compensate. Richard Hamilton, the club’s third-year shooting guard, looked the part of a ready-made Jordan disciple, with a hair-trigger midrange shooting stroke and inexhaustible stamina for moving without the ball. But he also had his own bona fides—a national title and All-American status with UConn, a No. 7 draft slot—and chafed at the notion that he needed to be tucked under anybody’s wing. When Jordan sat out to tend to his knee, Hamilton hardly hid his pleasure. “The guys take pride and want to show we can play without Michael,” he said after one such game, per Leahy. “Hopefully he can watch and maybe get an understanding of our games.”

The team’s other young centerpiece, rookie big man Kwame Brown, presented even more challenges. In his last major act in the front office in June 2001, Jordan had drafted Brown with the first overall pick out of high school, seeing in him a collage of potential. He had unteachable size and speed, with a frame that could support top-tier NBA muscle. A post move or two and he’d dominate, the thinking went. But Brown entered the league out of shape and raw; he fumbled passes, cuffed rebounds and forgot plays. One trait irked Jordan more than the rest, as it represented what he saw as a shortcoming in his own diligence. In the locker room before a road game during Brown’s and Jordan’s second year together, Jordan would vent to Charles Oakley, an offseason signing and longtime MJ confidant. “God, I would never draft a big man who couldn’t palm the ball,” Jordan said, repeating the sentiment within earshot of Brown. Wyche asked why he’d done so, then; the team had had access to all the combine measurables. “It’s a lesson learned,” Jordan replied.

As it became apparent that the team’s stated goals were likely out of reach, Jordan’s public posture shifted. He spoke in increasingly defensive terms, not of sowing the seeds for lasting success but of girding his reputation. He kept to the rear of the team planes, smoking cigars, venturing forward primarily to up the ante in his teammates’ card games. He feuded with Pollin, at one point footing the bill for the team to stay downtown on the road, instead of at a hotel closer to the airport owned by the owner’s brother Harold. Having spent his entire career in the luxury of pure stakes—the pursuit of being the best player on the best team in the world—Jordan had to make do with smaller motivations and cherish more fleeting victories. When a reporter commented on a hot streak by noting that Jordan had averaged 35 points over his last four games, he shot back, offended by faint praise. “That surprise you?” he asked.

But stretches like those were a surprise. Some nights, Jordan would flub a dunk attempt or have his jump shot blocked by the likes of Voshon Lenard—a three-point specialist and fine role player but nobody’s idea of a stopper. Wyche remembers a murmur among the press seats on that occasion. “It was, ‘Whoa, O.K., this is a different MJ.’” The remainder of the games fell somewhere in the middle, Jordan logging his 20-something points fitfully: pump-faking more than he once had, leaning back at a steeper degree, searching out fissures in defenses he’d once simply risen over.

The knee, which would cost Jordan much of the final third of the 2001–02 season, became a metaphor: for what its owner had to deal with and for how impressive it really was that he could. “It was honestly the most disgusting thing I’ve ever seen,” remembers Etan Thomas, then a young forward for the Wizards. “His knee was swollen like the elephant man, and the doctor took out this long needle and extracted this black tar, goo-looking stuff out of MJ’s knee. He was writhing in pain.”

Afterward, Thomas asked Jordan why he bothered. “He looked at me and just kind of stared at me, but he didn’t have an answer.”

The Wizards’ heady plans unraveled: a 37–45 record in Jordan’s first year back, with their old, new star missing 22 games, and an identical mark the next season, despite him playing all 82. Between seasons, the team unloaded Hamilton and brought in Jerry Stackhouse, to little effect. Still, the gambit remained a box-office success. Washington sold out its home arena every night and drew packed houses on the road. “He was still a shot in the arm,” Jackson says. “It was just more about the man than the team, at least to my mind.”

To fans, Jordan’s return had the powerful twin pulls of nostalgia and celebrity. For league figures, his comeback captivated for different reasons. The way a failing mind can hold onto essential memories, great athletes in decline isolate their core characteristics. It was true, this ground-bound and loss-saddled Jordan was haughty, frustrated, dismissive of his teammates. He faltered in ways that once would have been unthinkable. (In the 2002 All-Star Game, Jordan broke free into the open floor, lined up his steps … and clanked a dunk off the back rim.)

But he remained as competitive and thoughtful about his sport as ever, even when it was clear those qualities would get him nowhere near where he’d once been. Every so often came a game like a thesis statement: I can still play. Days before Christmas 2001, with three seconds left in a tight contest in Madison Square Garden, Jordan muscled Latrell Sprewell to the right elbow, leaned back and dropped in a game-decider. (“Firing … AND HITS!” went Marv Albert’s muscle-memory call.) Two nights after putting 51 on the Hornets, Jordan scored 45 against the New Jersey Nets. In a January game against the Bulls, his first against his former team, Jordan tallied 29 hard-won points, but the representative moment came after he had his shot blocked by Artest with 23 seconds left. Jordan griped for a foul but then turned and raced downcourt, tracking a Chicago fastbreak from behind. Ron Mercer tried a layup, and Jordan soared (the word could here be used legitimately, not nostalgically), snared the ball with two hands and pinned it to the backboard, preserving Washington’s six-point lead. Phil Chenier, Buckhantz’s partner at the broadcast table, remembers the play as an instant of pushback—against lacking teammates, diminished hops, a shot that could suddenly be tipped by defenders who once wouldn’t have gotten within a foot of it. “You could just see the energy, the emotion going into it,” Chenier says. “It was a great block.”

“There was a maturity level to his game, a perspective,” says Bryce Drew, who grew up near Chicago in Valparaiso, Ind., and guarded Jordan during his 51-point game against the Hornets. The reflexes were a touch duller, Drew remembers, and the burst more than a touch lessened; at one point, he swiped Jordan’s dribble. But in the midrange he was a composer, one variation setting up the next. “It was face-up shot, pump-fake, step-through, 12-foot finish,” Drew says. “It wasn’t the high-flying dunks. It was all skill.”

In total, over his last two seasons, Jordan scored 21.2 points a night on 43% shooting, with six rebounds, four and a half assists, and a steal and a half per game. Fans and pundits saw some sadness in the numbers, that perfect conclusion scuffed by a crummy coda. Jordan’s competitors—the players, coaches and executives whose matchup with the Wizards suddenly became loaded with significance—tended to look at it differently.

“The guy in the Wizards uniform solidified, in my estimation, why he’s the greatest basketball player of all time,” former Mavericks, Heat and Hornets swingman Jamal Mashburn says. Jordan used whatever was at his disposal—once, a vicious first step and powerful jump; now, the intimidation of his status and canniness of his footwork. “He was averaging 20 points a game on smarts alone.”

Mashburn remembers his lone appearance in an All-Star Game, in 2003. It was Jordan’s final fete, a weekend soaked in nostalgia. The game started with Vince Carter giving up his starting spot for Jordan; at halftime, Jordan tearfully addressed the crowd, saying, “Now I can go home and feel at peace with the game of basketball.”

For Mashburn, the more telling moment came during a lull in the pregame warmup. “I asked some questions about the fadeaway, and he not only shared some things but had an active scouting report going on in his head about my game,” Masburn says. “He told me to keep the ball closer to my body on the turn so it wouldn’t get stripped. He was like, ‘Jamal, you turn over your right shoulder 90% of the time. You need to have a counter, just show it once a game and it’ll open things up,’” Mashburn laughs. “I played against the Memphis Grizzlies right after that. That’s when I scored 50.”

The comparisons have been made too many times to count, by teammates, coaches, trainers and staffers: Traveling with Jordan was like riding on Air Force One or touring with The Beatles. Buckhantz’s entry into the lore of Jordanmania centers on water fowl.

The story goes that the Wizards had a road game in Memphis and stayed at the Peabody Hotel, where every day a gaggle of mallards waddled from their perch on the roof onto an elevator and down to the fountain in the lobby. A Peabody official approached the team and asked whether Jordan might lead the procession, as rock stars and politicians had done during their own stays. Per Buckhantz’s memory, George Koehler, Jordan’s personal assistant, put a question back to the would-be organizers. “Do you like your ducks?” Koehler asked. “Because if those elevator doors open up and Michael Jordan walks out, you’re going to have a lot of dead ducks.” That afternoon, Jimmy Carter led a perfectly tame version of the ritual.

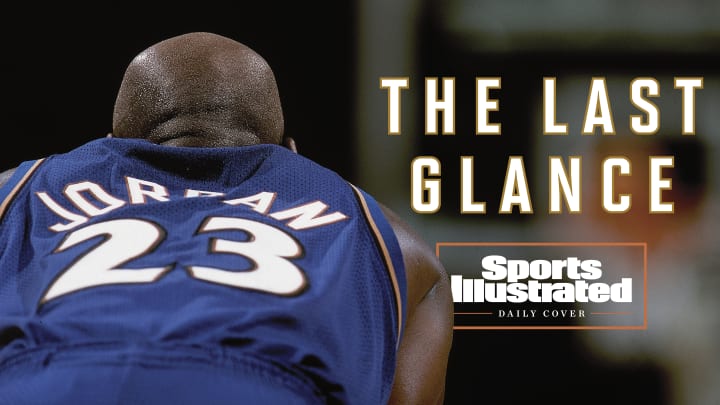

If that level of adoration led people to rush en masse for a glimpse of Jordan, it has also led them to endeavor to forget their last look at him. Jordan in dark blue belongs to a tucked-away file in America’s collective sports memory, next to Ali leaning on the ropes being pummeled by Berbick.

Johnny Smith, a professor of sports history at Georgia Tech writing a book on Jordan’s mass appeal, grew up in Chicago and remembers avoiding Wizards games when they were broadcast. “As a historian, understanding him better, it makes perfect sense. He had to feed his ego, and he thought that the best thing he could do to resurrect the Wizards was lace up his Nikes again,” Smith says. “But at the time there was something so jarring about it. It was like it invaded my own personal memories, my joy associated with him wearing a Chicago uniform.” The cleanliness of Jordan’s previous exit—the hand cocked in follow-through against a backdrop of Utah Jazz fans who all know what’s coming—emphasized a feeling that he now tarnished something precious. “There gets to be a collective fear that heroes will be diminished, that they can’t live up to the ideal they once created,” Smith says.

Now the heroics against Utah were painted over, one last time, by a rough night in Philadelphia. In Jordan’s final game, in April 2003, he scored 15 points in a 20-point loss; Allen Iverson scored 35. His relationship with Pollin had soured, the hotel incident just one yank in an ongoing tug-of-war over franchise influence, and his return to Wizards management—long a foregone conclusion—would not come to pass. Announcing his comeback, Jordan had stated that “we have the foundation on which to build a playoff-contention team.” What he’d done instead was turn a bad team into a slightly better, and much more famous, one.

It is a truism of coaching that you learn more from losing than from winning. The same can be said of whatever strange project fans undertake, this process of trying to understand something—about an individual, about achievement, about what pushes a person to success or consigns them to setbacks—via the way an athlete moves on a court. Throughout his career, Jordan had included a “Love of the Game” clause in his contracts, a bit of language allowing him to play in any game anywhere he chose away from NBA arenas. Like so many elements of Jordanian myth, this was hard to parse amid the confetti of championship parades. Did Jordan’s combativeness fuel his teams’ accomplishments, or did his talent let them succeed in spite of it? Did he work harder than everyone else, or did his athleticism let that work show? Did he love the game, or did he love winning it? “Jordan prided himself on that clause, it tapped into this idea that he was the most competitive man on earth,” Smith says. “But was he more competitive than Magic Johnson? Larry Bird? Isaiah Thomas? I don’t know how you measure that.”

This isn’t a measurement, but it is a story. Halfway through Jordan’s last season, the Wizards were 25–28, and the East-leading Nets came to town. Jordan had turned 40 four days earlier; the Nets had a trio of 20-somethings—Jason Kidd, Richard Jefferson, Kenyon Martin—who would end the year in the NBA Finals. The stakes, such as they were, had nothing to do with playoff seedings or psychological edges in a championship race. In the context of the broader basketball family, it was a bitter father and ascendant son having it out on the driveway.

Before the game, word had circulated that Jordan had an ailing back. Rod Thorn, then an executive with the Nets, remembers a misstep. “Before the game, Kenyon ribbed him a little, asked how his back was doing,” Thorn says. “Allegedly.”

With 30 seconds left in the fourth quarter and the Wizards down by one, Jordan deked, skipped into the lane and curled a left-handed finger roll over Martin’s reaching hand. They were Jordan’s 42nd and 43rd points of the night—the last time in his life he’d eclipse the 40 mark in an NBA game. The bucket put the Wizards up for good, and milling around on the floor afterward, as the Nets paid the respects a championship aspirant owes a fading icon, Jordan sought out Martin. “Allegedly,” Thorn says, “Michael said, ‘I think my back’s O.K.’”

More SI Daily Covers:

• Shawn Bradley Wrestles With Life at 7'6" in a Wheelchair

• NBA Replacement Players Don't Want the Ride to End

• Inside John Starks's historically bad Game 7 in 1994