Off the Grid: Growth of mobile QBs, Q&A with Pettine and Manziel, more

Remember Bobby Douglass? He was, once upon a time, the foremost running quarterback in the NFL, rushing for 986 yards, eight rushing touchdowns and an insane 9.6 yards-per-carry average in 1972.

If you have not heard of Douglass, it may be because he compiled stunningly average passing numbers for below-average teams that season. He completed 37.9% of his passes, which was a horrible number even in the chuck-heavy early 1970s. Douglass was a one-trick, one-season pony, and he proved then what we know now—that a running quarterback without a fully developed sense of the position and an evolved passing game around him is destined to failure sooner than later.

Mobile players who eventually found success as pure quarterbacks usually did it later in their careers, after they discovered that using your body to overcome your passing liabilities is a one-way path to a short shelf life in the NFL. In the late 1980s and early ’90s with the Eagles, Randall Cunningham set the league afire with the kind of athleticism we’d never seen before, but he also took an epic number of sacks. Despite his transcendent skills and one of the best and most underrated defenses you’ve ever seen, those Eagles couldn’t ever get over the hump—there was simply too much inconsistency from the most important position.

Yet by the time Cunningham landed with the Vikings in 1997, he had slowed the game down in his mind, he had a tremendous offensive coordinator in Brian Billick, and a stunning group of receivers in Cris Carter, Jake Reed, and (in ’98) Randy Moss.

Week 15 NFL Power Rankings: Injuries, upsets shake up AFC’s best

Cunningham shined as a pure quarterback in 1998. He led the league with a 106.0 passer rating, threw 34 touchdowns to 10 picks, and eight percent of his passing attempts went for touchdowns. It was too late in his career for an extended turn of excellence as a pure quarterback, but Cunningham gave us a brief and thrilling glimpse of what might have been. As did Steve Young after years studying under Joe Montana in Bill Walsh’s offense. As did Michael Vick in one amazing season with the Eagles in 2010—formerly a one-read quarterback with incendiary running ability, Vick bent his will to meet Andy Reid’s and Marty Mornhinweg’s offensive concepts in ’10, and he showed that he could use his mobility and deep passing ability to become a cutting-edge West Coast Offense quarterback. Like Cunningham, Vick came to the full aspects of quarterbacking a bit too late to make a long run with it, but there was a similar stretch of tantalizing play.

As the new wave of mobile quarterbacks came into the league in the early 2010s, it appeared for a while that the same transition would take place. After being selected by the Panthers with the first pick in the 2011 draft, Cam Newton spent his first couple of seasons in a hybrid offense that merged what he’d learned at Auburn with what he needed to do in the NFL. Washington’s Robert Griffin III, taken second in the 2012 draft, had one season of statistical shine in a Mike and Kyle Shanahan system that fit him perfectly before injuries and scheme transitions relegated him to the scrap heap. Seattle’s Russell Wilson, taken with the No. 75 pick in the 2012 draft, leaned on a great running game, a historically strong defense and the occasional explosive play to make his way to the last two Super Bowls.

And then, 2015 happened, and we’re now seeing a mixture of demon speed, pure athleticism and true quarterback awareness like never before.

For injured WR Benjamin, Panthers' magical season is bittersweet

Now, Newton is seen by many as a lock for the NFL MVP award, and he’s leading the 13–0 Panthers as opposed to following in the pack. Wilson is producing at an absolutely ridiculous rate right now—in the Seahawks’ last four games, the fourth-year quarterback who was allegedly too short to get things done in the pocket has completed 81 of 99 passes for 1,094 yards, 15 touchdowns and no picks... from the pocket.

Also this season, Tyrod Taylor has been a revelation in the Bills’ offense run by coordinator Greg Roman, whose previous responsibility was turning Colin Kaepernick into an NFL-ready quarterback in San Francisco. The former Ravens backup who was taken in the sixth round of the 2011 draft currently ranks seventh in DVOA and 12th in DYAR (Football Outsiders’ opponent-adjusted efficiency metrics), and he’s one of the game’s best deep passers, with 23 completions in 56 attempts of passes 20 yards or more in the air, with 10 touchdowns and three interceptions.

Why the change? There are many reasons, for a longer column down the road, but the main difference is that NFL coaches have finally learned to tailor offenses to fit their athletic quarterbacks without dumbing down the systems over time.

When I spoke with Panthers coach Ron Rivera at the 2012 combine after Newton’s rookie season, he told me of the importance Carolina’s coaching staff placed on mixing what Newton already knew with what he needed to learn. They didn’t try and retrofit him into a bastardized version of the West Coast offense overnight, like the Falcons tried with Vick in the mid-2000s.

When the Seahawks drafted Wilson, they understood that their offense was a combination of West Coast passing and two-back zone power running, and Wilson was the right guy for that system. He had run a WCO passing tree at North Carolina State, and a ton of two-back power at Wisconsin, so the battle was half-won. And with Taylor in Buffalo, Roman learned from the mistake made with Kaepernick in San Francisco—when you’re developing a quarterback, you don’t confine him to the pocket when he’s not yet ready to live there.

The trend bodes well for the future of quarterbacks in the NFL, and the league is benefiting as never before.

Q&A: Johnny Manziel and Mike Pettine

It’s been said that Browns coach Mike Pettine and Johnny Manziel don’t see eye-to-eye regarding the quarterback’s development on and off the field, his preparation for the game and Pettine’s preference for what a quarterback needs to do. I decided to try a thought experiment and ask both of them the same questions on Wednesday while they were preparing to face the Seahawks this Sunday. I found that the two men are pretty similar in their overall outlooks.

Doug Farrar: When it comes to Manziel’s ability to create from the pocket and read the full field, how have you seen him improve in the last year? And how has his preparation improved?

Mike Pettine: [He’s] much better, and that just comes through knowledge and understanding NFL defenses. I think last year, when he got out there, it looked like there were 13 or 14 guys out there on defense. Whatever cliche you want to use—the game slowed down for him—he understands what we’re trying to do when a pass play is called. Then, he has to take the next step of the process—versus this coverage, I’m going to go here, versus that coverage, I’m going with that route. And then, anticipating what route’s going to come open, taking his drop accordingly, and if he’s got to move in the pocket and change his arm angle to make a throw, he can do it.

That’s where he’s improved—if the first or second read is there, go ahead and take it. ... When you’re not confident in your reads and throwing the ball, you look to improvise too much. We all know it’s a skill he has, and we don’t want to coach that out of him. But you don’t want to turn dropback passes into punt returns 15 plays a game—there’s a time and place for that.

Johnny Manziel: I think it was more daunting last year than this year. I think Brian Hoyer set a good example last year of being a veteran guy who was always in the building, taking care of your body and doing it the right way. It was different in college—it’s different than going to class and only being in the building for a certain amount of time. Was it a lot different than I had imagined? Yeah. But I’m to the point where I’ve embraced coming to work every day and enjoying everything involved in being a starter,staying late and doing everything you need to do on Sundays, because that’s the answer.

Why playoff teams are likely hoping Steelers stay on the outside looking in

There’s so much to learn about this game. Who’s covering who, who’s lined up and what does it mean, who’s rolling down into this coverage. How do they play the bunches? How do they play stack [formations]? How do they play this personnel versus that personnel? That’s been one of the more fun things this year—learning the little ins and outs of how defenses play. Moving forward, that’s the part for people who play in this league for a long time—knowledge of the game and defenses and how to play certain things. That’s the next level and the big step for me. ... Mentally, when you get to a certain point where it becomes second nature, and you just click through certain things offensively, reads and progressions, that’s where you can do some damage.

DF: When Manziel came back from rehab, and when he got past these recent off-field issues, how was he able to regain a trust and connection with you and the team?

MP: He proves it to us every day, and he has done that. The saying we use, that I talked about when all this happened at the bye, is that with trust, you lose it in buckets and you regain it in drops. The reason he hasn’t lost his coaching staff and lost his teammates is that when he’s here, he’s all about football. He’s prepared, he knows that to do, he handles his business, he asks the right questions. It’s clear that he’s thinking about football when he’s here and when he leaves the building. It’s easy for us as coaches and teammates to have faith in him, just because of the way he carries himself every day.

JM: For me, it’s not been about what I say. Right now it’s just about what I do, so coming into the building every day, asking the right questions, taking good notes and keeping my head down. I didn’t say a whole lot—I just did everything right for an extended period of time. That was the best way for me to approach it.

DF: Both Manziel and Russell Wilson, the quarterback you’ll be playing this Sunday, have to balance the ability to create plays out of chaos with the need to make plays in structure. How does Manziel do it at this point in his career?

MP: I think that’s a great question, and it’s really valid. ... I think the system helps Russell—it gets him on the move a decent amount, and he’s not always throwing from a pocket. He does a good job of making his own space and getting out where he needs to. I think where Russell’s been exceptional, and I think Johnny has it as well ... you get some quarterbacks, especially young ones who get out of the pocket, and they look to run first.

Both of these guys have done a good job of keeping their eyes downfield and [making plays when you're] wondering whether they were across the line of scrimmage, making big plays down the field. So, that’s always a concern with defenses; it’s the first question they ask. If the guy’s a scrambler, does he scramble to run, or to throw it? Both of these guys make their big plays with their eyes downfield.

JM: As you play more and more, there are certain things you can and can’t do at this level, because [defenders] are too fast, and they make up too much ground. There is a fine line, but once you eliminate so many of those mistakes from trying to do too much all the time, you can be calm and handle the chaos.

History lesson: When the AFL stood up for civil rights

The Missouri football team's recent decision to boycott games until the university's racist atmosphere was addressed (and the fallout) put me in mind of the most prominent civil rights gesture in pro football history. It happened in 1965, and it wasn’t the NFL. It was the American Football League, and it was the players’ response to the environment in New Orleans for the league’s All-Star game. The game was set to be played at Tulane Stadium on Jan. 16, and the city was hoping to get an expansion team in either league. But when the players arrived in New Orleans, they found a welcome far less warm than they had anticipated.

The Disappearing Man: The Raider who went missing before Super Bowl

“We were sitting on the bus to go to the first practice,” said Chargers Hall of Fame offensive tackle Ron Mix in Jeff Miller’s book, Going Long, an excellent oral history of the AFL. “Sid Gillman, the West coach, was taking roll. ‘Bobby Bell!’ No answer. ‘Earl Faison!’ No answer. Somebody said, ‘Hey—all the black guys are missing!’ And somebody from the back of the bus said, ‘They’re meeting back at the hotel.’ Sid said, ‘What about?’ ‘When they arrived at the airport, they couldn’t get cabs. Then, they wanted to go out to eat and were turned away at restaurants. They’re thinking of boycotting the game.’”

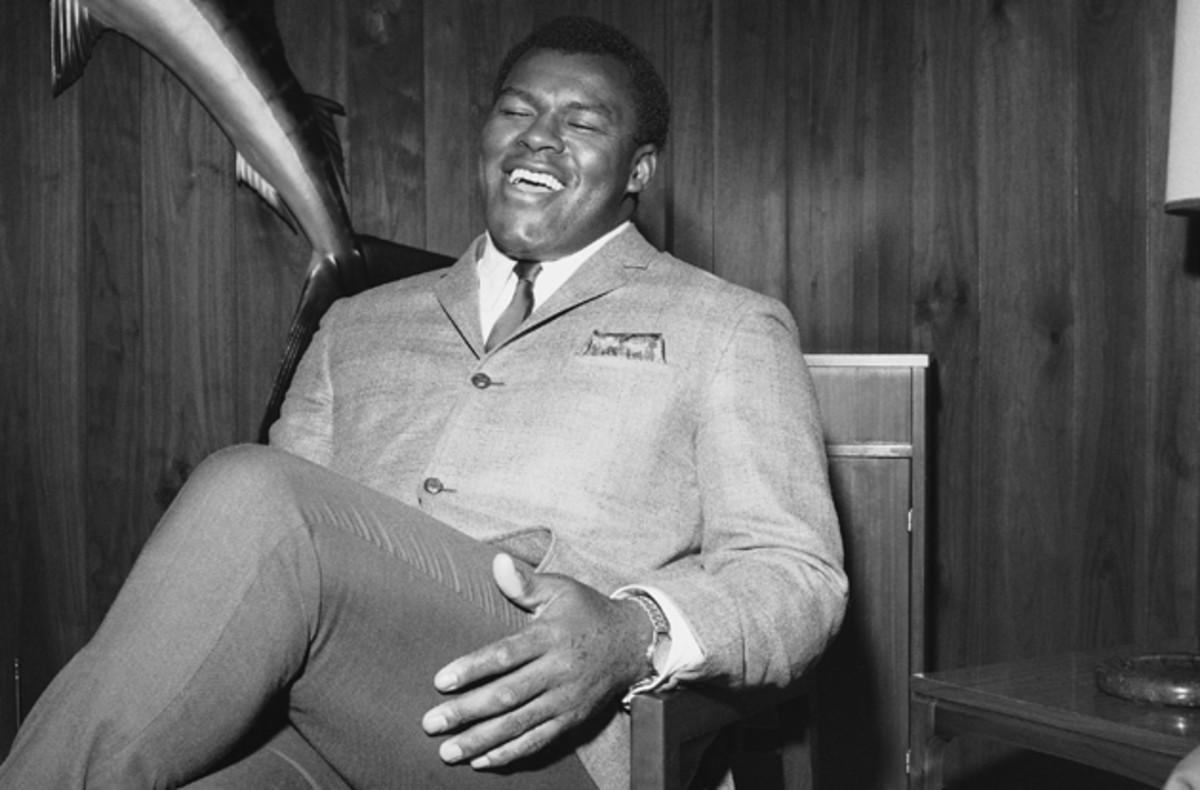

Mix got off the bus and headed to the meeting, which was led by Bills running back Cookie Gilchrist. Eventually, all players on both teams decided to stand with their colleagues—the decision was made to boycott the game.

The league, led by Commissioner Joe Foss, decided that it could not afford a boycott of an All-Star game—the AFL had been formed in 1960, and needed to show out at all times to maintain and forward key relationships with the television networks that eventually gave them the resources to take the NFL on and force a merger. So, Houston Oilers owner Bud Adams offered the use of Jeppensen Stadium, his team’s home field, in an emergency gesture. The hastily-altered All-Star game was played to a crowd of less than 16,000.

The East team won, 38–14, but this was on obvious example of the score not meaning a thing. That the players stood up for their equality, and that all players on both teams agreed to stand whether they agreed or not, was a really big deal—especially back then, when sweeping civil rights legislation had just been passed.

"It didn't get the publicity I thought it should have," said Boston Patriots defensive tackle Houston Antwine in Going Long. "We didn't feel it was properly addressed. Back in Boston, there was one little blip in the paper showing me with my bag, leaving the hotel. That was basically it. The hostility and treatment we received in New Orleans was never, never really publicized. Right now, if you ask somebody, 'Do you remember the AFL All-Star game that was supposed to be played in New Orleans?" nobody remembers what happened."

Well, most people don’t. One year later, the NFL awarded a franchise to New Orleans, in part as a thank-you gesture for Congressional approval of the AFL-NFL Merger. But that wasn’t the first big pro football story that came out of New Orleans—the first big story was about the smaller league, and a handful of players who took a stand.

BRO-fficial Review: Dean Blandino doubles down on Rex Ryan

Dean Blandino, the league’s VP of Officiating, has a tough job. Not only are his referees blowing calls at an all-time rate, he can’t even spend time on Jerry Jones’s party bus without people freaking out. Here, we give Blandino, the most bro-like NFL executive, equal time to counter the slings and arrows headed his way.

"Remember -- it's not Oh-fficiating, it's BRO-fficiating! pic.twitter.com/LqKHtLGi5M

— Doug Farrar ✍ (@NFL_DougFarrar) December 14, 2015

“Sup, Br-Obi Wan Kenobies! So, Bills coach Rex Ryan needs to chill with our refs. After Buffalo's loss to the Eagles last Sunday, he, like, went OFF on a bro-tacular tantrum.”

Rex Ryan not happy with the officials after the game. In their ear the whole way off the field #Bills pic.twitter.com/oaawjizFZn

— Joe Buscaglia (@JoeBuscaglia) December 13, 2015

“Like, pick plays? Those are complicated, bro, and what’s more, Ed Hochuli was the main brofficial! Ed and his pythons!”

/imitates barbell curls

//high-fives assistant

///drinks Bud Light

“Let’s be real, dude. BRO-fficiating is a Broller coaster at the best of times. You can’t come off like some kind of Teddy Brosevelt and say whatever you want. Our Bromissioner, Roger Brodell, has, like, rules against that! Just chill, Rexbro! You, like, used to be jolly! Que pasa?”

Turkey(s) of the Week: Qualcomm Stadium security

The Chargers’ home stadium has suffered from issues for ages; it’s the primary reason they’re in the pole position to move to Los Angeles sooner than later. And whatever you think of NFL teams taking public money to finance their facilities, it certainly seems that the security in this particular stadium could do a better job of making all game attendees feel welcome.

On Dec. 6, Verinder Malhi and three of his friends traveled from Fresno to San Diego to see their beloved Broncos play the Chargers. When they arrived at the stadium, Malhi’s party—followers of Sikhism, an Indian faith—were told that they had to remove their turbans if they wanted to go inside.

Eventually, the stadium employee told Malhi and his friends that they could enter the stadium, but if they ever came back, they would have to remove their turbans. Yes, turbans are headgear associated with the Muslim faith as well, but it’s bad enough to automatically associate Islam with terrorism without any connection. To associate any person of a certain complexion, wearing a particular kind of headgear, with terrorism, is so beyond the pale, it’s just as easy to call it out as pure prejudice.

Roundtable: What will media coverage of Super Bowl look like in 50 years?

At some point during the day, someone in the stadium parking lot called local police about Malhi and his friends, saying that three men wearing turbans were “fiddling” with items in the trunk, and then left the parking lot. Police cleared the car after checking it out with a bomb-sniffing dog. Malhi said that he and his friends had simply returned to their car to place a bag there that they had not been allowed to bring into the stadium.

“Everybody [was] kind of confusing us with the turbans, because what you see on TV is mostly the terrorists—they wear turbans,” Malhi said. “But our turbans [are] different, our faith is different, our beliefs are different.”

Not to those who seem to believe that if you’ve seen one person in a turban, you’ve seen them all. Yes, recent attacks have made us all more vigilant. But the rise in hateful dialogue directed at Muslims and other people who don’t look enough like “us” has led to an outbreak of harassment in this country. This is one of the more benign examples, but it behooves Americans of any stripe to know better—or, at the very least, to avoid the assumption that everyone who looks remotely similar has the same evil intent.