What Jerry Richardson the Owner Learned from Jerry Richardson the Player

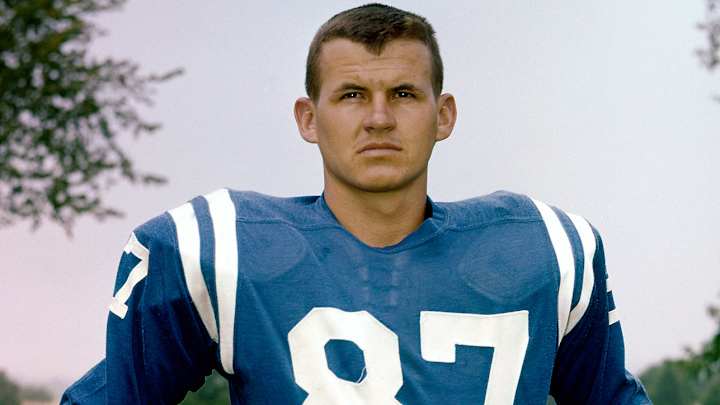

SAN FRANCISCO — It was the summer of 1959, and a young receiver on the Baltimore Colts had earned a special distinction. Johnny Unitas had taken a liking to him.

“Probably because he was catching everything,” explains Hall of Famer Raymond Berry, one of the veteran receivers on that team. “John kind of liked those guys who caught everything.”

The kid had a good mind for the game, too, and experience playing in a collegiate offense that passed the football, something of a novelty in those days. A 13th-round draft pick, he’d come to Baltimore without a car. So The Golden Arm would pick him up and drive him to practice every morning. That was nothing compared to the favor Unitas did for him in one of the preseason games: He threw him the ball; seven catches in a half.

The Colts had won the NFL Championship in 1958—in the Greatest Game Ever Played—and this kid would be a part of the following year’s run. He got the last receiver spot on the roster, thanks in large part to Unitas. Baltimore ran a double-wing offense in those days, lining up four receivers across the formation. Berry was split out on the left, and the kid lined up on the same side in the slot.

Fast forward to that year’s NFL Championship Game. The Colts were back in it, playing the Giants. Early in the fourth quarter Baltimore, leading 14-9, was deep in Giants territory, looking to extend its lead. Out of that four-receiver formation, Berry ran an inside route, the young receiver ran an outside route, and the latter was wide open. Unitas looked his way—this time for keeps—and the kid took the pass into the end zone for a 12-yard touchdown.

Baltimore won, 31-16, and along with the championship, Unitas’ young buddy earned a title-game bonus. That check, worth $4,674, is the reason the Carolina Panthers are playing in Super Bowl 50. The receiver’s name: Jerry Richardson.

* * *

In Charlotte two weeks ago, when Carolina-blue confetti rained down at Bank of America Stadium on the edge of downtown, that was the vision Richardson has had in mind since founding the team 22 years ago.

The thrill of the Panthers’ dominant 49-15 win in the NFC Championship Game wasn’t something the owner put into words, however. Richardson is a man of few words. Always has been. Even this week, with his team the toast of the NFL, Richardson was content to hang in the background. He hasn’t done any interviews, choosing to let the personalities of his players and coaches tell the Panthers’ story.

But you can’t tell the Panthers’ story without Richardson, who put so much care into building a team for his native Carolinas that he went so far as to select flowers indigenous to North Carolina to be planted on the north side of the team’s stadium, and South Carolina for the south side.

In 1993, Richardson became just the second former professional football player, after George Halas, to own an NFL franchise. At a victory rally in Charlotte that year, he famously pledged that the team would win a Super Bowl within the first 10 years. The Panthers almost did, if not for running into the Patriots dynasty in Super Bowl XXXVIII. Now they’re back, this time as the favorites against Peyton Manning’s Broncos.

• ORAL HISTORY OF THE ’95 PANTHERS: Carolina’s inaugural NFL season was one wild and crazy ride

“It’s been 20 years in the making, and we’ve been close several times before but hadn’t been able to take the final step,” says Mark Richardson, Jerry’s son. “So it’s been very rewarding to see it all coming together. I think it caught a lot of people off guard. They didn’t see it coming.”

Which speaks to what Richardson has done to build this team. He’s made the right moves, even if some were questioned at the time by insiders or outsiders: Drafting Cam Newton No. 1 overall. Sticking with Ron Rivera when the head coach won just 14 of his first 36 games. Keeping defensive heartbeat Thomas Davis under contract for 11 years through three ACL tears. Deciding not to re-sign Greg Hardy, the organization’s best pass rusher, after his arrest and trial for assault of an ex-girlfriend.

There have been rough patches on the road to seeing this vision through. In 2009 Jerry fired both of his sons, Mark, the team president, and Jon, the stadium president. A year later, in 2010, a roster that had been purged of talent stumbled to a 2-14 finish—though that debacle awarded Carolina the No. 1 pick, which it would use on Newton.

During the CBA negotiations in 2011, Richardson earned the reputation of a hardline owner who was unyielding in pursuit of a better deal for the NFL. So adamant was he in his stance about the revenue split between owners and players that during a meeting in Dallas over Super Bowl week, he ruffled some feathers when he leaned across the table and asked Peyton Manning if he understood what a profit-and-loss statement is. Today, Manning said he has “great respect” for Richardson and that they’ve shaken hands and exchanged stories about their Colts days when their football paths have crossed—as they will Sunday.

During one tense day of those labor talks, Giants co-owner John Mara turned to Richardson, who’d received a heart transplant two years earlier. “I don’t know whose heart you got,” Mara said to him, “but that had to be a tough son-of-a-bitch.” Richardson stared at Mara with a stern look. Then, he broke out into laughter. The former player in Richardson has steeled him for the reality that the road to success is not an easy one.

* * *

The significance of that $4,674 was that it ended up being seed money for Richardson’s first venture as an entrepreneur. He walked away from the NFL in 1961, two years after winning that NFL title, over a contract dispute of a couple hundred bucks. He headed back to Spartanburg, S.C., where he had played college ball at Wofford, with that bonus check.

Together with his college quarterback, Charles Bradshaw, Richardson opened a Hardee’s restaurant in their college town. They made enough money to open another one across town. And then a third, and a fourth, and so on. He started by helping to flip burgers and sweep floors. As business blossomed, Richardson and Bradshaw merged and acquired other restaurants, growing their company into a multimillion-dollar food-service conglomerate that controlled nearly 3,000 restaurants.

• CAM NEWTON—SON OF BLINN: What the Panthers QB learned in his year at a Juco in rural Texas

The hamburger business wasn’t an accident. When Richardson played for the Colts, two of his teammates, Gino Marchetti and Alan Ameche, opened their own fast-food business, selling 15-cent burgers in Baltimore. Its name: Gino’s. Richardson learned the tricks of the trade from them. “A classic case,” Berry says, “of the American Dream.”

That wasn’t the only business practice Richardson picked up during his years in Baltimore. The team’s owner, Carroll Rosenbloom, was a magnate in the clothing business—“America’s Overalls King,” according to one publication—who had a keen eye for how to run a winning, and profitable, professional sports franchise. He tabbed a little-known assistant offensive line coach for the Cleveland Browns, Weeb Ewbank, as his head coach, and Ewbank led Baltimore to those back-to-back NFL championships in ’58 and ’59. (He later led the Jets to victory over his old team in Super Bowl III.)

“The man was a genius, and one of the greatest entrepreneurs who ever walked the face of the Earth,” Berry says of Rosenbloom. “The exposure to him would have to enlighten you if you were the least bit interested or observing, and Jerry was interested and observing. I’m sure there was something about Carroll Rosenbloom’s leadership characteristics that had to rub off on Jerry Richardson.”

Not to mention that playing on a championship team showed Richardson what it took to build a team and see it through. Mara believes that experience helped inform Richardson’s patience when many were calling for Rivera to be fired. Many times during Super Bowl week, Rivera has brought up his gratefulness to Richardson for staying the course, and he’s also referred to encouragement he draws from their weekly meetings.

Richardson used his fast-food fortune to buy an NFL team because it married his two lifelong loves: football and business. What made the Panthers purchase, a $200 million investment, even more worthwhile to him was that he was bringing the team to his home state, rather than having to go elsewhere. His son Mark, then 27 and a recent MBA graduate from the University of Virginia, spent six and half years laying the groundwork in the city of Charlotte. Richardson was awarded the franchise after presenting a plan that included a privately funded stadium, bolstered by the brainchild of selling personal seat licenses.

• RETREAD SUPERHEROES: How Carolina gets the most out of castoff veterans

It didn’t take long for Richardson to be appointed to some of the league’s most important committees, including chairman of the stadium committee, a reflection on the respect he instantly commanded within league circles.

“He’s as influential as any owner we have,” Mara says, even though Richardson’s recommendation for the joint Carson project in Los Angeles between the Chargers and the Raiders was overruled in favor of Stan Kroenke’s Inglewood plan for the Rams. Richardson supported the Carson project because it solved the worst two stadium problems in the league and gave a nod to St. Louis’ efforts to keep its NFL team. The vote from ownership for Inglewood, despite Richardson’s lobbying for Carson, was less a reflection on Richardson’s sway than on the magnificence of Kroenke’s Inglewood presentation.

“I will tell you this,” Mara says, “had it not been a secret ballot, a number of owners would have had tough time standing up and announcing they were voting for Inglewood in front of Jerry Richardson.”

Mara is not one to speak effusively if he does not mean it, and he means it. When his father, Wellington Mara, was dying of lymphoma in 2005, Richardson was a frequent visitor to his bedside. Last February, when John’s mother, Ann, passed away, Richardson sent Mara a handwritten note: “When I first came into the league, your parents said they were going to watch over me. Now that they are gone, I am going to watch over you.”

* * *

Fullback Mike Tolbert recalls one of his first conversations with Richardson in 2012, his first season after signing with Carolina. He’d caught a pass over the middle in a game, and he’d been tackled by a single defender.

“Hey Butterball,” Richardson said, using the nickname he’d come up with for Tolbert. “I didn’t bring you here for one guy to tackle you now.”

“OK,” Tolbert replied.

“OK?” Richardson fired back.

“Yes, sir?” Tolbert tried, instead.

“There we go,” Richardson told him.

Says Tolbert now, “That’s when I was like, now I see what kind of guy he is. And I appreciate that.”

Always a man of few words, Richardson, 79, is known for offering brief snippets of advice when players come to visit him on the golf cart he rides around practice. “The No. 1 job for the receiver is to catch the ball,” he reminded Jerricho Cotchery once. Sometimes, of course, the situation calls for more.

When special teams coach Bruce DeHaven was diagnosed with prostate cancer this spring, Richardson told him whatever he needed—access to the best care available, whether he wanted to continue coaching or not—they’d make sure he got it. Richardson extended the same generosity to tight end Greg Olsen, when Olsen’s son was born with a congenital heart defect that has required multiple surgeries. Richardson offered his private plane, and accompanied the Olsens to a doctor’s consultation in Boston. The boy, T.J., was given the middle name Jerry in gratitude.

Richardson has been through similarly trying situations himself. He needed the heart transplant in 2009. In 2013, his older son, Jon, died after a battle with cancer. That was another time, Mark says, when his father’s emotions could not be read in his words but rather in the look in his eyes.

The severing of his sons’ Panthers ties was a business decision, one that Mark still declines to discuss in detail, but their personal relationship is separate. Mark Richardson has shifted his focus to his commercial real estate company and also serves on the Clemson Board of Trustees.

“I’m a fan of my father’s, and I’m proud for the role I have played in the organization, helping start it and bring it to the Carolinas,” Mark says. “My dad has already announced that when he passes, the team is going to be sold. That’s what is going to happen. I have accepted that, so I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about it being different from that. I’m peaceful, and happy, and content, and enjoying the ride they have been on.”

To win the Super Bowl this Sunday, and fulfill the promise Richardson made to Charlotte two decades ago, would be “monumental,” Cam Newton says. The clock has been ticking for the Panthers since that day, and the 2009 heart transplant, Mark says, “brought it home a little bit more, that none of us live forever.”

• ROAD TO SUPER BOWL 50: All of The MMQB’s stories and video from our cross-country journey to San Francisco#SB50RoadTrip

It’s been seven years since the Super Bowl Sunday when Richardson was notified that a donor heart was available. It’s been 57 years since he caught that pass from Unitas to be part of an NFL championship team. A win this Sunday in Super Bowl 50, Mark says, would bring his dad’s football life full circle.

“I watch the Super Bowl every year, and at the end of the game they bring the stage out and they shoot the confetti and they hand the Lombardi Trophy to the winning owner,” he says. “And it is a wish I have always had for my dad. Every year I look and say, I wonder if he is going to have that opportunity, to be the owner who got to raise the trophy. I believe this year is the year, and I think it is finally going to happen.” And if it does, we’ll finally hear the man speak.