Roger Goodell Under Oath: No-Call Lawsuit Means Deposition for Commissioner

The legal system can’t change the controversial outcome of January’s NFC Championship Game. The Los Angeles Rams won. And the New Orleans Saints lost.

The legal system can, however, create problems for the NFL on account of what took place during the game.

To that point, a judge in Louisiana has ordered that NFL commissioner Roger Goodell explain, under oath, why the Saints were the victims of a bad no-call.

Judge Nicole Sheppard of the New Orleans Civil District Court has directed Goodell and three referees from the game—Patrick Turner, Gary Cavaletto and Bill Vinovich—to be deposed in New Orleans in September. The order is the latest ruling in a civil lawsuit brought by Louisiana attorney Antonio “Tony” Le Mon and three other Saints fans (Susan Boudreaux, Jane Preau and William Preau, M.D.) who had purchased tickets to the NFC Championship Game. These ticketholders argue that they were victims of NFL fraud and deceit. They demand a jury trial and at least $75,000 in damages. The plaintiffs pledge to donate any money they receive from the NFL to charities, including Steve Gleason’s charity, Team Gleason.

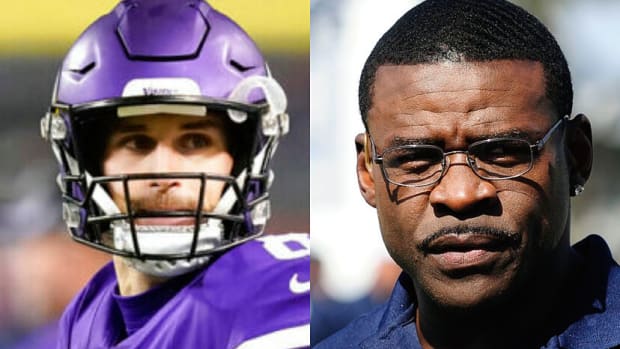

The lawsuit stems from what happened with 1:49 left in the fourth quarter of the game, which was played on Jan. 20. Rams cornerback Nickell Robey-Coleman committed what seemed certain like pass interference when he pushed Saints wide receiver Tommylee Lewis out of bounds. There was also helmet-to-helmet contact. The Saints and Rams were tied 20-20 at the time.

If the penalty call had been made, the Saints would have been first-and-goal inside the 10-yard line. They would have been nearly guaranteed to win and go on to play the New England Patriots in Super Bowl LIII.

Instead, the Saints settled for a field goal. The Rams then rallied to tie and, in overtime, defeat the Saints, 26-23.

The no-call spurred massive criticisms of NFL officiating and, by extension, Goodell—a commissioner who has ultimate authority over game officials and a commissioner who has repeatedly stressed the essentiality of the “integrity of the game.” The no-call also spawned litigation. On Feb. 1, Le Mon and his co-plaintiffs sued the NFL, Goodell and the referees.

Understanding the case against the NFL

The Le Mon case is premised on alleged detrimental reliance, among other theories of unlawful conduct. In this context, “detrimental reliance” refers to the ticketholders asserting that they relied, to their detriment, on certain consumer assurances made by the NFL and Goodell.

In legal filings obtained by Sports Illustrated, the plaintiffs insist that they took the NFL at its word when the league marketed games as containing fair gameplay. The plaintiffs argue the NFL betrayed this promise “by selecting NFL officials for the NFC Championship that are from or live in the Southern California region that clearly acted with prejudice in favor of the Los Angeles Rams in the instant situation.” Such a sentiment captures the fact that Cavaletto lives in California (though there is no evidence that him being from California altered his officiating).

Similarly, the plaintiffs insist that they purchased tickets and spent other monies on NFL merchandise “believing that the NFL and Commissioner Goodell provided NFL officials who would fairly and impartially enforce the rules of the game.”

To be clear, the plaintiffs do not argue that they possessed a right to watch a perfectly officiated game. In fact, they “accept that human error occurs by players, coaches, and NFL officials during any NFL competition.”

The plaintiffs nonetheless distinguish ordinary human error from what took place in the NFC Championship. There, the plaintiffs charge, “the infractions against a player [were] blatant and clearly observed by NFL officials.” The plaintiffs also highlight “clear errors in judgment” by Goodell in methods he used to select and evaluate officials. They further reference a failure by the league to utilize “available mechanisms to correct such a grievous injustice to one NFL team to the benefit of another NFL team.” Le Mon and his fellow plaintiffs also draw attention to “the lack of use of available technologies immediately after such a grievous injustice to correct that injustice.”

For these reasons, Le Mon and his co-plaintiffs contend that they “received a product far inferior” than what was promised by the league and Goodell. They insist had they “known that the NFL and Commissioner Goodell would fail to have safeguards in place to allow such travesties to occur without immediate corrective action,” they would not have “invested funds.”

Le Mon and the three others in his case claim to have experienced legally-cognizable harm from the no-call. They say they “suffered great emotional trauma, past, present and future relating to this travesty.” The so-called “travesty” also allegedly caused them “the loss of enjoyment, past, present and future of the opportunity to enjoy and observe the celebration of the New Orleans Saints as the true and NFL declared NFC Champion.” The plaintiffs go further to contend that “this travesty has not only caused great emotional harm and loss of enjoyment . . . it has [also] created a lack of future enjoyment and entertainment with the disillusionment to [the plaintiffs] as to the future fairness and impartiality of NFL officials.”

The lawsuit does not seek injunctive or equitable relief. Stated differently, even if the lawsuit prevails, it would not change the outcome of the game or re-write NFL history. The record books will continue to state that the Rams defeated the Saints, and that the Rams went on to lose to the Patriots in the Super Bowl.

The Saints are also not plaintiffs in this litigation. In fact, they are technically a defendant in the sense that they are part of the unincorporated association of franchises that constitute the NFL and the NFL as a defendant.

The NFL’s legal defenses

The NFL and its attorneys clearly regard this lawsuit as frivolous and completely without merit. That doesn’t mean the league should be confident it can easily extinguish the claims.

Along those lines, the league is no doubt aware that Judge Sheppard is an elected official in her first term in office. Her New Orleans-based constituency presumably consists of many Saints fans. According to Ballotpedia, Judge Sheppard is also the host of three local television talk shows Real Life, Traffic Time and Real Life: Law Edition. None of this is to say Judge Sheppard is biased against the NFL. However, there are always types of concerns with elected judges that are different from those of appointed judges.

The league has retained the New Orleans law firm Jones, Swanson, Huddell & Garrison to represent them in this matter.

In a filing on Monday, the NFL categorically denied the plaintiffs’ claims. In doing so, the league invoked a number of arguments:

• There is “no contractual relationship” between Le Mon and his co-plaintiffs and the NFL. This is because the plaintiffs’ relationship to the game was limited by their game ticket.

• The plaintiffs’ “allegations as to the outcome of the football game are entirely speculative.” While the Saints probably would have won the NFC Championship with correct officiating, it’s not certain what would have happened if the call had been made. Remember Malcolm Butler shockingly intercepting Russell Wilson in Super Bowl XLIX. Games aren’t over till they are over.

• The NFL took “all required corrective action” required by its rules. This point refers to the league claiming that it fulfilled its obligations. The fact that a different set of NDFL rules for instant replay might have yielded a different outcome in the NFC Championship is irrelevant in terms of the law. The NFL had a system and it used it.

• Le Mon and the other plaintiffs have no right to “compel an apology” from the NFL. Saints fans might want an apology. On some level, they probably deserve one. But that is not a legal claim.

• Le Mon and the other plaintiffs “received the full benefit of the licensee that they received when they purchased the ticket to the game.” This argument refers to the fact (which is explained more fully below) that a game ticket provides a revocable right to enter a facility to watch a game—and that’s about it.

The league is advantaged by the fact that lawsuits brought by disappointed fans have historically failed.

As mentioned above, NFL game tickets provide a very limited set of rights. Such rights include the ability to enter a stadium on a specific day to watch a game between two teams from a particular seat. Stadiums’ codes of conduct also ensure that ticketholders are provided a safe experience.

Game tickets do not provide much else. There is no contractual guarantee of “good officiating,” just as there is no contractual right to see particular players on NFL teams play.

As the NFL sees it, Le Mon and other ticket holders received exactly what they paid for: the ability to safely watch the Saints play the Rams from particular seats in the Mercedes-Benz Superdome.

While the plaintiffs are clearly upset by the no-call, being upset is not, by itself, harm the law ought to remedy. This principle explains why a Miami Heat ticketholder unsuccessfully sued the San Antonio Spurs over Gregg Popovich “resting” Tim Duncan, Manu Ginobili, Danny Green and Tony Parker and why a New York Jets ticketholder unsuccessfully sued the Patriots over the team violating a league policy on the position of cameras. Those ticketholders received what they paid for: the right to safely watch games from particular seats.

As a related point, the fact that people bet on the NFC Championship also does not mean that judges should review bad calls or bad no-calls. People who bet on sports are aware, or should be aware, that bad calls and no-calls happen during games. Those calls (no calls) are, in effect, part of the game.

Furthermore, a bettor—or a sportsbook, for that matter—probably lacks standing to bring a lawsuit over a bad call. They are not in contract with the NFL or teams. Instead, they are freeriding off of the work of the league and its teams and players. In short, buyer beware.

NFL has reasons to not settle the case

It’s possible that the litigation could be resolved before Goodell is deposed. Now that the NFL is faced with the prospect of Goodell having to answer questions posed by opposing counsel, the league might aggressively explore settlement talks with Le Mon. Goodell might surmise that he is better off reaching a settlement than answering questions. It’s possible the league could offer $75,000 or some other figure in exchange for Le Mon dropping the lawsuit. The money could then be donated to charity.

Yet this is a tricky case to settle. The plaintiffs are not, at least according to their court filings, seeking to profit from the litigation. As noted above, they claim they’ll “donate any and all damage recoveries made in this litigation.” From that vantage point, Le Mon and his fellow Saints ticketholders seek not money but an opportunity to force Goodell to explain himself. Throwing money at them might not persuade them to drop the case.

The league also doesn’t want to create a precedent whereby they settle lawsuits brought over officiating. Even if the NFL would not be required to apologize or issue any statement in connection with a settlement, the mere act of settling with Le Mon would be interpreted as a tacit acknowledgment of fault and weakness. This could incentivize other ticket holders to sue over bad calls.

What Goodell will likely be asked while under oath

Assuming the case remains on the docket by the time Goodell is required to testify, Goodell would presumably comply with Judge Sheppard’s order that he testify. If he ignores the judge’s order, he could be charged with contempt of court. Here are likely questions and topics:

• Rule 17 of the NFL’s Official Playing Rules refer to the commissioner having authority to investigate an in-game “calamity” that is “so extraordinarily unfair or outside the accepted tactics encountered in professional football that such action has a major effect on the result of the game [and] would be inequitable to one of the participating teams.” Rule 17 authorizes the commissioner to take any corrective measure, including starting a game over or re-starting from right before the “calamity” occurred. Goodell will likely be asked if he considered invoking this authority and if so, why, or if not, why not.

As a rebuttal, Goodell will likely caution that under the language of Rule 17, the rule “will not apply authority in cases of complaints by clubs concerning judgmental errors or routine errors of omission by game officials.” In other words, Goodell will insist Rule 17 was inapplicable to the situation presented in the NFC Championship.

• Other leagues have done “do-overs.” Baseball can replay games if they don’t last at least 4.5 innings. Or take the NBA. Eleven years ago, then-NBA commissioner David Stern mandated that the Atlanta Hawks and Miami Heat replay the final 51.9 seconds of a game because of a miscount of the number of fouls assessed to Shaquille O’Neal. The official scorer thought O’Neal had six fouls, and O’Neal fouled out. In reality, O’Neal only had five fouls. Goodell could be asked if he considered how other leagues have employed do-overs.

As a rebuttal, Goodell could stress the numerous practical hurdles of a “do-over.” Given the tight NFL playoff schedule, when would a do-over occur? How would the league handle game tickets of the 73,023 in attendance? How about obligations with NFL broadcasting and advertising partners? Goodell would also warn that once he approves a do-over, he opens the floodgates to be asked to do so again.

• Goodell often referred to the “integrity of the game” during the Bountygate and Deflategate controversies. He could be asked if “integrity” is only selectively sought.

• Goodell could be asked to discuss how he evaluates officials and whether any league owners complained to him about officiating in the NFC Championship. Likewise, he could be asked to detail which steps he took in response to such constructive feedback.

• Goodell might be asked to share emails and texts related to officiating. In response, he might insist that such information constitutes protected trade secrets.

• Goodell could be questioned if he knows of any information to suggest that the particular NFL officials in the NFC Championship were biased. He will probably be asked if he and other league executives knew of the officials’ ties to California.

• Goodell might be asked if he favors certain teams and ownership groups over others.

As a general strategy, Goodell would stress that the decisions he makes are completely within his discretion. This means that even if he could have made a different decision, he was under no obligation to do so. Goodell can’t be the “judge, jury and executioner” in a dispute where there is an actual judge, but he could nonetheless stress that he has tremendous discretion and thus complaints about his decision-making do not give rise to actionable legal claims.

Michael McCann is SI’s Legal Analyst. He is also an attorney and Director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire Franklin Pierce School of Law.