NFL’s Plan for Incentivizing Minority Coaching Hires Goes Well Beyond Draft Picks

Last Friday, news that the NFL would consider incentivizing minority hires for general manager and top coaching positions boomeranged around the league. It elicited an array of questions: How would this work? Would it make a difference? And for some black coaches, who have lived the very problem at the root of this proposal, they wondered why this was the first time they were hearing about an idea they viewed as unhelpful—or even insulting.

Rod Graves, the executive director of the Fritz Pollard Alliance, the independent group that works to advance minority representation in the NFL, heard his own share of the feedback.

“Some people are going to be offended by the fact that these type of programs have to be encouraged on owners to hire black candidates,” Graves says. “But I choose to compliment the league on its efforts and wait for further discussion, because I think this is the beginning of a fruitful conversation for really advancing diversity.”

The incentive proposal, which is scheduled to be voted on during a virtual owners meeting Tuesday afternoon, would be the first use of football currency—in this case, draft picks—to spur clubs to hire, and retain, minorities in top roles. It’s a bold idea, one that warrants the debate and scrutiny it’s gotten over the past few days. It’s also just one part of a plan the NFL will begin rolling out this year to directly address the embarrassing lack of diversity in the leadership ranks of a league composed of about 70 percent black players.

There’s no quick fix for a problem as pervasive as the color barrier in a league that has just four head coaches and two general managers of color. That is one criticism of the incentive proposal, which would bump teams up six slots in the third round for hiring a minority head coach, and 10 slots for hiring a minority GM, if they are still employed at the following year’s draft. Additional incentives would apply if the head coach and GM are still with the team heading into a third season (five slots up in the fourth round); for teams that hire a minority as their QB coach (compensatory fourth-round pick); and for former teams of minority candidates hired away as a head coach or GM (compensatory third-rounder) or coordinator (comp fifth-rounder).

Beyond the outcome of Tuesday’s vote on the incentive proposal, the NFL has spent this offseason formulating a broader action plan. Among the measures drawn up to address the root causes of the unbalanced hiring practices:

• The Rooney Rule will be extended to require teams to interview at least two external minority candidates for head coach and at least one minority candidate for any of the three coordinator jobs (no vote is required on this). Additionally, the league office and clubs must include people of color and women in searches to fill top executive positions, including the club president, who often has a hand in hiring of the head coach and GM.

• The league office and all 32 clubs will adopt diversity, equity and inclusion plans, based on a model created by the league office, and will hold implicit and unconscious bias training this coming fall or winter.

• All 32 teams will hire a season-long minority coaching fellow, with an emphasis on working with the offensive coordinator and QBs coach, the roles that produce the majority of head coach hires.

• The NFL’s new chief people officer, Dasha Smith, will lead a leaguewide data collection about diversity hiring across organizations, to be able to measure progress.

• Creating ways to use the Senior Bowl week for career development, such as allowing the head coaches of the two NFL staffs coaching in the game to designate a coordinator or assistant to serve as the head coach for the week, or inviting owners to attend an event where they can interact with aspiring HCs and GMs.

“This is a more aggressive conversation than I’ve witnessed since I’ve been involved with the NFL,” says Graves, who spent three decades in NFL front offices, including 11 years as the Cardinals GM. “Whether or not ultimately this has the effect we are looking for, it does insinuate the league is taking the conversation seriously.” And, for good reason.

* * *

Have you ever been on a job interview in which you wondered if you were only there because of the color of your skin? And that you therefore knew you had no real chance of getting the job? And you then had to swallow the uncomfortable way that made you feel, because the opportunity to interact with power brokers in your field was rare enough that you couldn’t pass it up?

This is not a concept many white Americans understand. But for aspiring black head coaches and aspiring black general managers in the NFL, this is a reality of pursuing their dream jobs. The barriers they often encounter, that their white counterparts don’t even have to consider, have too often been minimized.

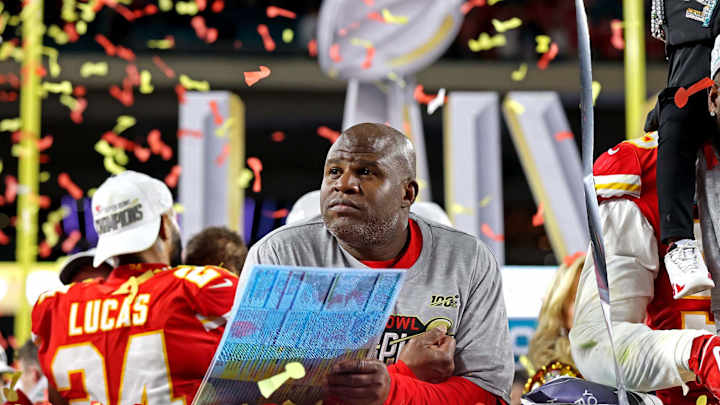

The problem became impossible to ignore, though, after the most recent hiring cycle, when Chiefs offensive coordinator Eric Bieniemy was passed over despite being a leading figure in the team’s Super Bowl run and being effusively endorsed by Andy Reid. This was the third straight year in which only one person of color was hired as a head coach—a total of three minorities hired for 20 vacancies. The numbers are even worse in the GM ranks, and it’s not lost on people around the league that the two black GMs—Miami’s Chris Grier and Cleveland’s Andrew Berry—climbed the ladder within their organization (Berry left for one year, to Philadelphia, before returning to the Browns). This year’s NFL draft broadcast, in which only a team’s highest-ranking decision-makers were on camera, reinforced the whiteness of the NFL’s leadership.

It’s been 17 years since the Rooney Rule was introduced, requiring teams to interview a minority candidate for head coach and their top football operations job. While it served an important role in opening up interview opportunities to overlooked minority candidates, over time its effectiveness has waned as many clubs have—at times brazenly, like when the Raiders telegraphed their hire of Jon Gruden—followed the rule by letter only. Black coaches have shared accounts of owners and executives from the club they are interviewing being late to their meeting, or not calling any of their well-positioned references, indications that they were not being seriously considered for the position. They were a box to be checked.

“If we are not going to adhere to the spirit of that rule in terms of opportunities, true opportunities, then that’s when the rule gets to be a sham in the eyes of those who participate,” Graves says. “That is something we have to work to correct.”

The idea behind the incentive proposal, similar to practices in corporate America that tie bonuses to diversity goals, was to buttress the Rooney Rule. Right now, its only teeth are the rarely imposed fines for teams who do not comply with the basic interview requirement. Some black coaches fear, though, that these draft-pick incentives not only would have no impact on the decisions owners make but could actually reinforce some of the racial barriers that often stunt their career paths. In a league that has seen a team hire two minority head coaches in a row only one time—the Colts’ in-house transition from Tony Dungy to Jim Caldwell—people of color already face a tough fight against tokenism.

“In my opinion, you are telling people, Hey, if you hire this guy, we attach a bonus to them. They need a bonus for you to look at them,” says Ray Horton, who recently retired after spending last season as Washington’s DBs coach. “We don’t want a bonus; we don’t want an incentive. We want an equal opportunity to be viewed on our merits.”

Horton went on a number of head-coach interviews that didn’t pan out during his 25-year career as an NFL defensive coordinator and position coach. He recalls once being asked, “Why did you cut your hair?,” referring to the long braids he had previously worn. In another interview, he says the team’s owner hesitated before finally asking him why he looked so “aggressive” when he saw him on the TV broadcast during games. When Horton was turned down for one job, the feedback he remembers receiving from the team president was that the owner felt “more comfortable” with the candidate they hired, a too-common refrain that leaves black candidates wondering why exactly that is.

Agent Brian Levy, whose Goal Line Football group represents Horton, Bieniemy and about 70 other coaches, the majority of whom are black, is often asked by his clients, “Do you think I’ll ever be a head coach?” His reply: “I can’t answer that question.” Bieniemy’s being passed up this past year, despite his success in the same Chiefs offensive coordinator role that previously produced two head coaches, reinforced to him that the target keeps moving for minority candidates. Levy’s reaction to the incentive proposal was that it shows the issue is being acknowledged, but he did not believe it would be well-received by the majority of his minority clients.

“I don’t think owners will be motivated by moving up a few slots,” Levy says. “The people we work with are qualified because they are phenomenal coaches, not because of the color of their skin. They don’t want to get hired with an asterisk next to their name. I don’t think that’s fair to them.”

Graves said the Fritz Pollard Alliance was not directly involved in the crafting of the incentive proposal—that came from the owners’ diversity committee working group—but he was aware that there were discussions around draft-pick or salary-cap incentives, as a way for the league to wield the capital in its control to address a serious and long-standing problem. In his view, whether or not the proposals as written are the ones that are implemented is less important than the league ramping up its efforts to address the lack of diversity in its leadership.

“This is going to come down to how assertive the decision-makers and owners are willing to be to tackle this problem,” Graves says. “I tend to believe there has to be something that puts the onus back on owners; it has to be a commitment. That commitment can be displayed in a number of ways, but if there’s not a commitment toward diversity of leadership then we won’t have it. I do know it’s possible because we have seen examples of it through league history from individual owners. … What we have not been able to do up to this point is doing it on a collective level.”

* * *

At his press conference before Super Bowl LIV—a game that featured Bieniemy and 49ers defensive coordinator Robert Saleh, two top-performing coaches of color who would have to wait for another turn in the hiring cycle—commissioner Roger Goodell spent several minutes addressing the shortfalls in the hiring of qualified minority candidates. “It’s clear we need change,” Goodell said in January.

In the months that followed, Troy Vincent, the league’s EVP of football operations and liaison with the owners’ diversity committee, led efforts from 345 Park to formulate a plan for addressing the hiring inequities. At the combine in late February, he and Goodell met with members of the owners’ diversity committee, which is chaired by Art Rooney II and includes Ozzie Newsome, and representatives from the Fritz Pollard Alliance. Buffalo defensive coordinator Leslie Frazier talked in front of the room about his experience of not getting an interview request this past hiring cycle, and Hue Jackson and Baltimore’s David Culley also shared their personal experiences. It was a snapshot of the frustrations many minority coaches share.

“Their stories were very impactful and really underscored the problems of where we are with hiring,” Graves says. “We have stressed from Day One that the league purports a policy of being fair, open and competitive, and we believe that the league and every team should adhere to that. That means when candidates are brought in, that process is truly fair, open and competitive. Otherwise why have the Rooney Rule?”

Graves says the NFL has been “very open door” this offseason to the feedback from him, Dungy and others with the Fritz Pollard Alliance. He describes this as the beginning of a two- to three-year effort to both make changes and also evaluate if those changes are having any effect. Other ideas being discussed include formally pulling in members of the Alliance to a league advisory panel on diversity and reinstituting a new version of the Stanford Program, in which the league office and each club would appoint an executive to attend a training program, with topics including diversity and inclusion.

One of the main gaps in the hiring pipeline is the number of minorities who are offensive coordinators or QB coaches, roles that were stepping stones for about three-quarters of the head coach hires from 2017 to ’20. That’s where having all 32 teams participate in the year-long coaching fellowship program, earmarked for minority offensive assistants, will help. The NFL’s only other black offensive coordinator outside of Bieniemy is the Bucs’ Byron Leftwich, who began his coaching career as an offensive intern on Bruce Arians’s Cardinals staff in 2016. Last season, Arians hired Antwaan Randle El in a similar role. The NFL is also looking to create more flexibility in the Bill Walsh Diversity Coaching Fellowships, so that candidates who may have other commitments during mini-camp or training camp can still participate.

Senior Bowl director Jim Nagy is working with the league office to use the all-star game week, when clubs have more free time than they do during the combine, as a helpful tool for networking and development. Last year, the Senior Bowl partnered with the NFL to create six intern positions for women to work with the video, athletic training and equipment staffs. One idea being discussed for 2021 is to offer Bill Walsh fellowships for Senior Bowl week, staffed with aspiring NFL coaches from HBCUs. Getting team owners to Mobile, a trip they traditionally do not make, would also create a new access point for them to meet rising coaches and executives informally. Part of leveling the field for minority candidates is creating networking opportunities so the first time they are meeting a club owner or team president is not necessarily when they walk into an interview room.

In addition to the incentive proposal, the owners’ diversity committee drafted a second proposal that will prevent teams from blocking an assistant coach to interview for a coordinator job or a club employee to interview for an assistant GM role (except for the period between March 1 and the draft, for personnel hires). Clubs would also not be allowed to include in contracts provisions restricting upward mobility, such as right-to-match clauses or requirements for compensation if the employee leaves for another team. This resolution, which would eliminate hurdles to assistants and personnel evaluators advancing, is almost certain to pass. The incentive idea may require further discussion, or could even be tabled to a later date.

“At this point, I see it as a first proposal and welcome the league’s approach that this is a serious issue that deserves serious items on the table,” Graves says. “Hopefully, this opens the door for many more discussions along this line. I’m hoping at a minimum, it elevates the awareness of owners to really do something much more aggressive and something that contains a greater commitment than what we have seen up to this point.”

He adds: “I see this going far beyond what is introduced (this) week.”