Not even minor-league struggles could shake Jordan's confidence

Jordan always liked (still likes) to talk about other sports, and he grew animated when the subject turned to track and field, Bubka's specialty. Jordan said that fooling around one day in high school he did 6-foot-5 in the high jump and also cleared 23 feet in the long jump. Both would be extraordinary efforts, particularly the long jump, for someone just "fooling around." But, then, Jordan was (still is) an immensely confident fellow, who thought (still thinks?) that with some work he could join the senior golf tour. (He could not.) He probably didn't long-jump that far or high-jump that high. And I doubt, even with years of minor league seasoning, that he had a major league bat.

Though it was a massive shock when he announced in October of 1993 that he was quitting the NBA, it was little surprise to those who knew him when he subsequently proclaimed that he was going to try professional baseball and journey to spring training in 1994 with the Chicago White Sox. Jordan loved talking baseball and sometimes referenced the fact that as a 12-year-old he was named "Mr. Baseball" by the Dixie Association in his native North Carolina. Remember that on the night that news leaked out about Jordan's retirement from basketball, he had thrown out the first pitch at Comiskey Park for the White Sox ALCS playoff game against Toronto. He no doubt heard the full-throated roar of 44,000 and thought, "Hmmm ..."

Though it goes without saying that we lived in different worlds, I understood Jordan's wanting to get away from the NBA, for I was doing the same thing, giving up the beat for several years to do something else. After an amazing 10-year run topped off by the U.S. winning the gold medal in Barcelona, pro hoops was entering an inevitable downturn. Larry Bird had retired, Magic Johnson, having been diagnosed with the AIDS virus, wouldn't be far behind and the love-'em-or-hate-'em Detroit Pistons were on the decline. Power teams, natural rivalries and engaging personalities (Shaquille O'Neal notwithstanding) were in short supply. Jordan had won three championships in a row (none of us knew that three more were still in front of him), and he was growing weary of his Chicago Bulls teammates, the demands of his fame and the stories about his prodigious gambling, particularly the one from San Diego businessman Richard Esquinas, who had taken about $900,000 on the golf course from Jordan. The murder of Jordan's beloved father, James, in the summer of 1993 solidified his resolve to give up the game at which he excelled for one in which he was, well, a former 12-year-old star. (It's worth adding that, at age 12, I was considered a major league prospect within the walls of my own household.)

Let me say right now, as I have said before, that I have no idea whether Jordan was encouraged by NBA commissioner David Stern to walk away from the game because his gambling habits (obsession? addiction?) were becoming increasingly troublesome. If there is a smoking gun in that story, no one has yet found it. But I never thought that Jordan would use the proverbial spend more time with my family line. That wasn't him. Baseball was a natural outlet.

I was of two minds about Jordan's adventure. Yes, he would be taking the job of a more deserving individual, likely some kid who had spent 16 hours a day in a batting cage and who would've crawled on his nose through an army of fire ants to draw a minor league salary. On the other hand, there was something gallant about Jordan going into baseball at age 31, especially after the White Sox assigned him to Double-A ball in Birmingham. Even if he had deluded himself into thinking he could be a major leaguer, Jordan had to realize pretty quickly that he would never be a star outfielder and probably wasn't even a solid backup. The only time I had ever seen Jordan remotely embarrassed was during 1990 All-Star Weekend, when he entered the three-point shooting contest and made only three of his 15 shots, getting eliminated in the first round. (Of course, two years later, during the Finals against the Portland Trail Blazers, the same guy would make six three-pointers en route to 35 points in the first half of Game 1.) And here he was setting himself up for months of embarrassment in Birmingham.

Still, on Jordan plied in this strange out-of-the-spotlight season, saying all the right things as he worked hard, rode buses and shared cheap motel rooms with his Barons teammates, just two seasons after he and his fellow Dream Teamers had stayed in luxurious digs with armed guards in Barcelona. Years later I had cause to be in Birmingham on a few occasions and did several interviews about the one season that Jordan spent there. According to the people I talked to, Jordan had helped the community and minor league baseball in general just by being in uniform and not putting on a I'm-Michael-Jordan-and-you're-not attitude. They had nothing bad to say about what turned out to be a one-season diversion.

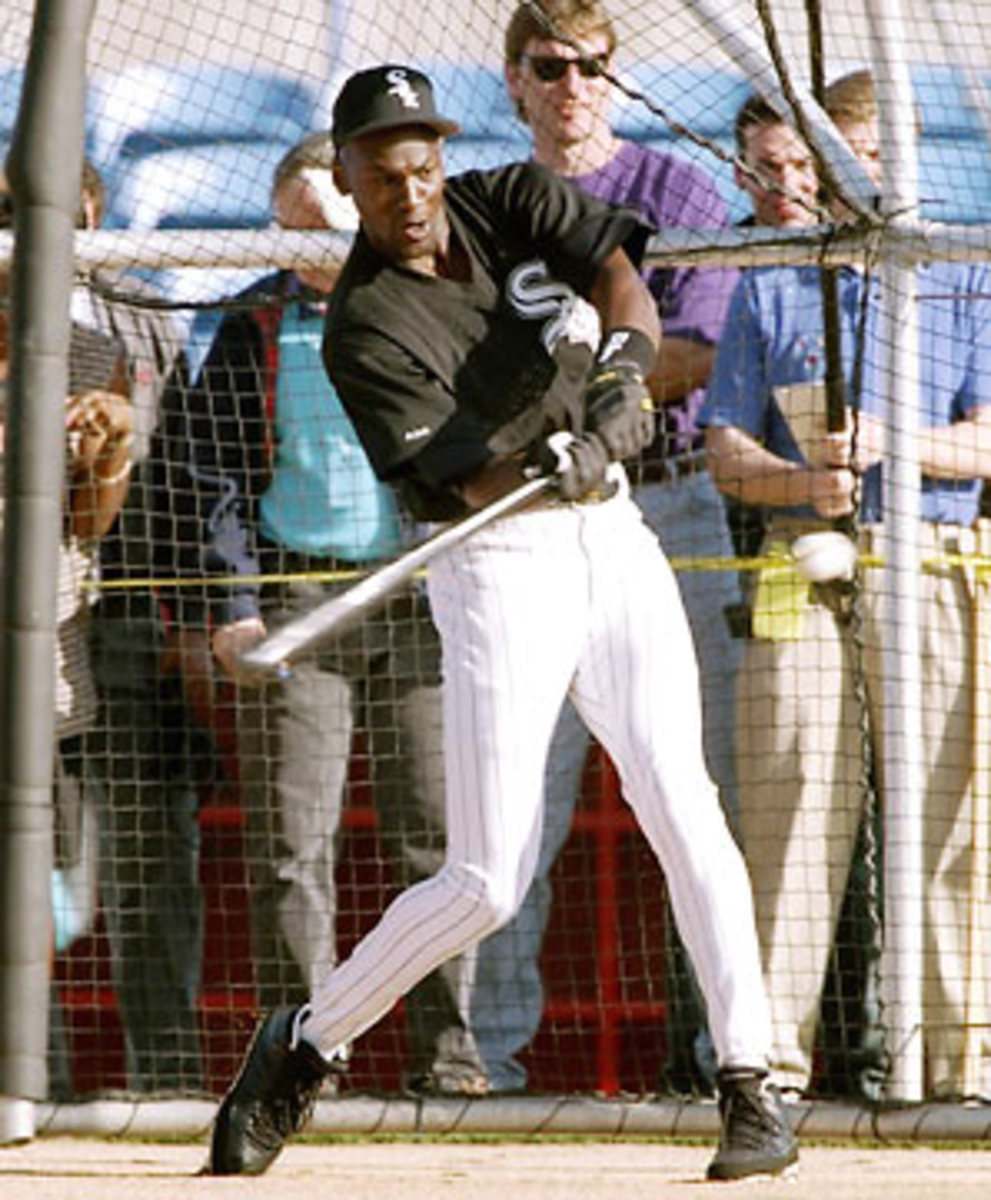

The lasting image I have of Jordan as a baseball player, though, is watching number 45 strike out, weakly, something he did 114 times in 127 games. Two words come to mind: slow bat. And if three words come to mind they are: painfully slow bat. Since Jordan the basketball player was not defined by his size -- his 6-6 height made him an average-sized NBA player -- we forget what a rarity he was, standing at the plate, hunched over, trying to find a stance, trying to come to grips with the same reality that millions of other hopefuls come to at some point in their lives -- that they can't hit major league or even minor league pitching. He finished with just a .202 batting average, three home runs and the rep of being a below-average outfielder. In true Jordan fashion, though, he wasn't bad in the clutch -- he had 51 RBIs.

MJ was back where he belonged in the spring of 1995, hanging a double-nickel on the Knicks in the Garden, lifting sagging NBA ratings, giving Nike a reason to live and setting up, beginning in 1996, another three-peat for the Bulls. In the final analysis, Jordan's year in baseball diversion was just that. In Steve Wulf's March 14, 1994, Sports Illustrated story about Jordan -- the one that bore the cover line "Bag It, Michael" and prompted his Airness to cut off official communication with SI for 15 years and counting -- Jordan bristled when presented with the notion that his basketball legacy might be tarnished by his brush with mortality in baseball. "If I strike out 15 million times, is that going to hurt my 32-point-whatever scoring average?" he said. "If I fail at baseball, does that make me less of a basketball player? If I'm a horse---- baseball player, that don't tarnish what I did on the court."

He was right. Even a less-than-successful return to basketball, when he came back with the Washington Wizards for two seasons in which his team didn't make the playoffs, couldn't do that.