O'Bannon expands NCAA lawsuit

Ed O'Bannon shocked the sports world in 2009 when he filed a potentially billion dollar class action lawsuit against the NCAA. O'Bannon, later joined by Bill Russell and Oscar Robertson as plaintiffs, contends that the NCAA and its member institutions are brazenly violating federal antitrust law. Coming under fire is the NCAA's policy of licensing the names, images and likenesses of former D-I football and men's basketball players in various commercial ventures without the players' permission and without providing them compensation. Earlier this year, the NCAA failed to persuade a judge to dismiss the lawsuit, which is currently in the pretrial discovery stage and is advancing towards a trial date, possibly in 2013.

On Friday, O'Bannon decided to take his lawsuit one step further: in a court filing, O'Bannon seeks a judge's permission to expand the class action to include current D-I football and men's basketball players. O'Bannon does not ask that current players be paid while in college. Instead, he wants a temporary trust set up for monies generated by the licensing and sale of their names, images and likenesses. Players could access those trusts at the completion of their collegiate careers. A star college quarterback like USC senior Matt Barkley, for instance, generates significant monies for USC and the Pac-12 Conference. Under O'Bannon's proposed trust, when Barkley finishes his time at USC, he would receive money for four years' use of his name, image and likeness. Under an economic formula proposed by O'Bannon, players would receive half of the NCAA's broadcasting revenue and one-third of video game revenue, with the remainder of revenue staying with the NCAA, conferences and colleges. Four-year players would likely accrue thousands or tens of thousands of dollars -- if not more -- in their trusts. Whether Barkley would receive more money or the same amount of money as a backup offensive lineman at USC -- or one at a less prominent D-I college -- remains to be seen, though O'Bannon's court filing suggests teams would have different values, but players on each team would share equally. Obviously, if a court approved the concept of trusts for current student-athletes, the mechanics of those trusts would require further litigation and debate.

U.S. Magistrate Judge Nathaniel Cousins will soon hold hearings to determine an appropriate class. If he grants O'Bannon's wishes, any current or former D-I football or men's basketball player could join the lawsuit. This could include marquee football players like Barkley and Arkansas's Tyler Wilson as well rising hoop stars like Indiana's Cody Zeller and Kentucky's Nerlens Noel. These players generate sizable revenue for their schools through consumer purchases of their jerseys and the positive impact of their image on ticket sales and television contracts. The NCAA, however, bars these players from receiving any payment other than reimbursement for tuition, room and board, books and other educational expenses.

The rationale of O'Bannon to seek an expansion of his class derives from what he and his attorneys, Jon King and Michael Hausfeld, have learned from the pretrial discovery process and from their expert economists, Roger Noll and Larry Gerbrant. In O'Bannon's view, the NCAA and member schools and conferences have illegally profited off the labor of college athletes for decades. Current and former D-I football and men's basketball players, according to O'Bannon, are common victims in this alleged exploitation and thus should be in the same class. O'Bannon also dismisses the series of documents student-athletes are required to sign as part of their participation in college sports. These forms require student-athletes to accept the NCAA's use of their name, image and licensing. If a player refuses to sign these forms, he will be deemed ineligible to play, which could jeopardize his athletic scholarship and ability to afford college. O'Bannon repudiates these forms as "contracts of adhesion" or unenforceable no-choice contracts.

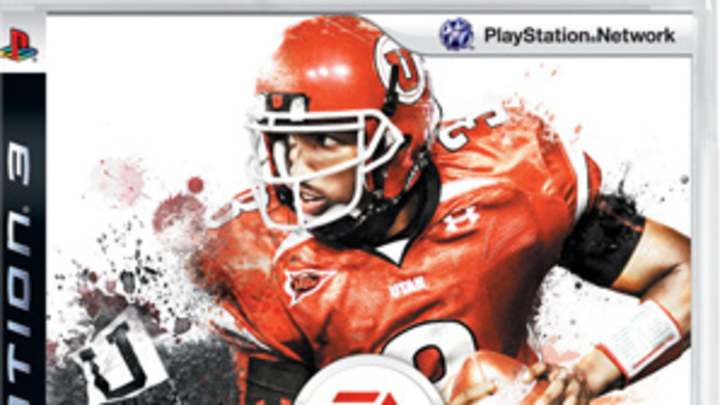

The desired expansion of O'Bannon's class may not end with D-I football and men's basketball players. If O'Bannon succeeds in this expansion, expect him to eventually go for it all -- a class that would include all current and former D-I athletes. While they generate less revenue than football and men's basketball players, baseball players, women basketball players, and various student-athletes in other sports still bring in "some" money to the NCAA and its member institutions. This is true when the Big Ten TV Network broadcasts field hockey and women soccer games. And it is true when the NCAA and its licensing partner, the Collegiate Licensing Company, earn revenue through a deal with ESPN to broadcast the College World Series each year and through a deal with Electronic Arts to publish the MVP NCAA Baseball 2007 video game.

Perhaps most importantly, many D-I student-athletes who are not on the football or men's basketball teams only have partial athletic scholarships -- sometimes for far less than half the cost of tuition. It's been said by some who are critical of O'Bannon that "these athletes get a free ride so they have no grounds to complain", but many whom the NCAA generates revenue from do not enjoy this "free ride". The prospect of NCAA athletes like Britney Griner and, eventually, Missy Franklin joining O'Bannon would also give O'Bannon's lawsuit a more inclusive dynamic. An open class would also be more threatening to the NCAA, which, along with its member conferences and universities, could face billions of dollars in damages.

The prospect of O'Bannon v. NCAA radically reshaping college sports is real. If O'Bannon ultimately prevails, "student-athletes" and "amateurism" would take on new meanings in the context of D-I sports. While college athletes would still not obtain compensation for their labor, they would be compensated for the licensing of their identity. If O'Bannon instead extracts a favorable settlement from the NCAA, these athletes would likely be compensated as well.

Still, it's early in the litigation process and, besides, the NCAA has a good record in court. The NCAA is sure to raise concerns about the new world of D-I college sports as envisioned by O'Bannon. For one, how a fund for current student-athletes is distributed and how former student-athletes are compensated will spark questions. Should star players get more? Would Title IX be implicated if male student-athletes receive more licensing revenue because they might generate more revenue than female student-athletes? Also expect some colleges and universities to bemoan that they cannot afford to contribute to player trusts unless they eliminate most of their teams and give pay cuts to coaches and staff. Along those lines, schools with large endowments or those with high revenue-generating teams may only become "richer" in a college sports world where certain schools have the financial wherewithal to compensate student-athletes while others do not.

Lastly, it stands to reason that star college players might be wary of joining O'Bannon's litigation. They could perceive litigation as distracting from their athletic and academic development. They may also fear being labeled "litigious". Such a label could harm their reputation with fans, coaches and with companies that might eventually seek to negotiate endorsement deals with them. While less likely, a player may even fear his draft prospects could be harmed by joining a controversial lawsuit.

One thing is for sure: O'Bannon v. NCAA should only get more interesting.

Michael McCann is director of the Sports Law Institute at Vermont Law School, a visiting professor at University of New Hampshire School of Law, and the distinguished visiting Hall of Fame Professor of Law at Mississippi College School of Law. He also serves as NBA TV's On-Air Legal Analyst. Follow him on Twitter.

Michael McCann is a legal analyst and writer for Sports Illustrated and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute (SELI) at the University of New Hampshire School of Law, where he is also a tenured professor of law.