Nationals' Nyjer Morgan enrages baseball by violating The Code

Baseball recently hit a sweet spot in this regard, thanks almost single-handedly to Nyjer Morgan.

The Washington Nationals' outfielder has been at the center of no fewer than eight Code-based controversies over the past seven days, all of which could have been avoided with a little more cognizance and a little less recklessly wild ego.

"The Code," of course, refers to the moral standards by which players police themselves and each other. They are expected, in this gentleman's game, to avoid running up the score through aggressive means; to handle their business within the context of the team, not the individual; and, above all, to respect each other on the field of play.

I spent nearly five years researching and writing The Baseball Codes, talking (in conjunction with my collaborator, Michael Duca) to some 250 ballplayers and ex-ballplayers about the topic, while reading thousands of newspaper and magazine articles detailing specific events.

The more I researched, the more the lines of demarcation became increasingly stark about what is generally acceptable within the boundaries of fair play, and what is not. Never once did I encounter such a blatant spate of disregard for the Code, in such a consistent manner, as that shown by Morgan over recent days.

It was his ill-fated mound charge on Wednesday night (some might also call it ill-considered, given that the 6-foot, 175-pound Morgan had to square up against 6-foot-8, 230-pound Marlins pitcher Chris Volstad) that grabbed national attention, but anybody who's been paying attention to the guy recently shouldn't be surprised. Over the course of a week, he's gotten into it with fans, his own manager and various members of the opposition, both as the player delivering punishment and the one receiving it.

Virtually all of it was grounded in the Code. A quick timeline:

Aug. 25: Morgan allegedly throws a ball at a fan in Philadelphia. The relevant unwritten rule -- somewhat unique, in that it has more to do with players' self-preservation than general respect -- says that ballplayers should never engage with hecklers because it rarely ends well.

In this case, the league quickly levied a seven-game suspension. Morgan, claiming a misunderstanding, has appealed the decision, and at least one fan has corroborated his account of throwing a ball to a fan, not at a fan.

Aug. 27: Morgan gets picked off first in the eighth inning of a close game against St. Louis, which proves particularly costly when the batter, Willie Harris, subsequently hits a home run. The Nationals lose, 4-2. Morgan is confronted after the game by Nationals manager Jim Riggleman, and dropped from leadoff to eighth in the batting order the following day.

Aug. 28: Morgan tries to level Cardinals catcher Bryan Anderson in a play at the plate, despite the fact that Anderson has his back to the play and is moving in the opposite direction. This means that Morgan's desire to take out the catcher draws him away from the plate; he's ruled ineligible to score when teammate Ivan Rodriguez spins him around near the edge of the cutout to go back and touch safely.

There are two sections of the Code at play here. One says that a runner should only try to take out a catcher when the plate is blocked so sufficiently that a slide would likely lead to an out. Even more importantly is the rule that says to never let personal vendettas get in the way of the team's success. In this case, Morgan's circuitous rout away from the plate was all about inciting violence -- Riggleman posited that Morgan was angry about his demotion, and took it out in any way he could -- and not at all about adding to his team's run total.

Riggleman was angry enough to call his player out in public, after apologizing to both Anderson and Cardinals manager Tony La Russa. Morgan did an "unprofessional thing," he told the media, and, indicating that lessons will be learned, said that "You'll never see it again." (In this regard, the manager was incorrect.)

He then benched Morgan for the series finale, under the auspices that the outfielder had become too prominent a target for the Cardinals to safely take the field.

Aug. 30: Morgan responds to Riggleman. "I guess he perceived it as some nasty play with the intentions of trying to hurt somebody before coming to me and asking me about the situation, which was very unacceptable," he tells The Washington Post. "But on my half, I'm not going to go ahead and throw fuel on the fire. I'm going to try to be as professional as I can about the situation."

It's frequently the case, of course, that whenever players feel the need to delineate the fact that they're being "professional," they're actually being anything but. (Code violation: Never call out your manager in public.)

Morgan, in fact, cited the unwritten rules in his own defense, saying that Riggleman "just basically did a cardinal sin. You don't blast your player in the papers."

Unless, of course, his behavior has deteriorated to the point where the manager feels he has few other options.

Aug. 31: It doesn't take long to stir up more controversy. In the 10th inning of a scoreless game, Morgan runs into Marlins catcherBrett Hayeswith such force that Hayes is later shelved for the remainder of the season with an injured shoulder.

Unlike his last collision at the plate, Morgan did not go out of his way to reach his target, but consensus held that he would have been safe -- with the go-ahead run, no less -- had he slid. (See previous Code citation about running into catchers. The Marlins then won with a run in the bottom of the frame.)

When he took the field for the bottom of the inning, Morgan again got into it with fans, this time being caught on tape cussing them out. (See previous citation regarding fan interactions.)

Any one of these items can constitute a distraction in the clubhouse. The sum of them, especially coming as they did in the span of a week, reads like the linescore of a borderline sociopath. (Morgan, wrote one poster to a Washington Post message board, is either on drugs, or needs them.)

Which leads us to Wednesday's firestorm.

It didn't take great insight to recognize the target on Morgan's back. The Code mandates retaliation for any borderline slide (in this case clean, but unnecessary) that injures a player.

When Volstad drilled him, it could have ended there. The pitcher went about things properly, hitting Morgan on the waist, and Morgan reacted appropriately, tossing his bat aside and heading to first without a word.

This moment illustrates the true power of baseball's unwritten rules. The Marlins had an ax to grind, they responded in kind, and the situation should have been diffused, allowing both teams to move on.

Key words: "should have."

Morgan, not content to take his punishment sitting still, stole second on Volstad's next pitch, then stole third on the pitch after that. The Nationals were down 14-3 at the time.

One of the prime unwritten rules mandates cessation of aggressive offensive tactics such as stolen bases and sacrifice flies when holding a big lead late in the game. In this case, however, Washington was behind, and it was only the fourth inning. The Code still holds, to a degree, although under ordinary circumstances a player's own teammates care more about him staying put in that situation than does the opposition.

Morgan's steals, however, were a clear message to the Marlins, conveying that he neither appreciated their treatment of him, nor respected their right to do what they did. There was no other way to take it.

"That's the only reason we tried to go after him a second time ..." Marlins third baseman Wes Helms told the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. "I cannot stand when a guy shows somebody up ... There's just no place in baseball for that. In my opinion, you're going to get what's coming to you if you do that."

Just like that, hostilities were reignited.

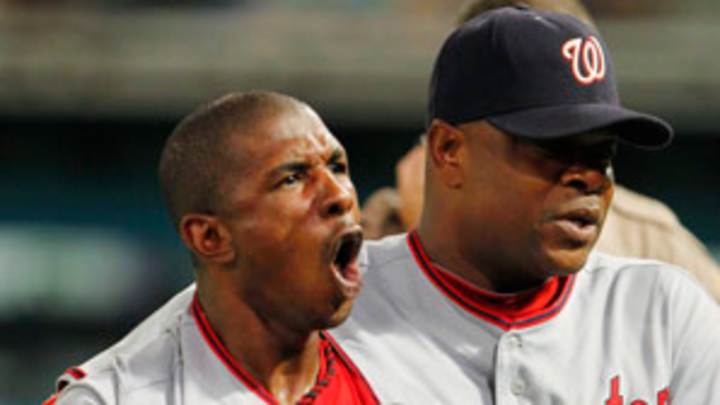

The next pitch that Morgan saw, in the sixth inning, sailed behind him, and he hesitated for just a moment before charging the mound. At that point, a rarity in baseball occurred -- a fight that involved actual fighting. The Marlins, particularly first baseman Gaby Sanchez, couldn't wait to get their hands on Morgan, and players quickly piled up near the mound.

Through the hostility, only one Code-based fight infraction stood out, and it had little to do with Morgan. The first guy on the pile after Morgan and Volstad was Nationals first base coach Pat Listach, despite the fact that the unwritten rules call for managers and coaches to serve as peacemakers during fights, not combatants. Listach is in line for league discipline for his actions.

Should Morgan be given any sort of pass in this situation, it's for the fact that his response to being drilled -- the stealing of back-to-back bases -- fell within the boundaries of reason; Florida was holding him on, which is frequently taken as a tacit green light for base runners.

Also, even more importantly, the Marlins had taken their shot earlier in the game. Between Morgan's steals and the injury to his catcher, Volstad can hardly be blamed for wanting to get in another blow -- but Morgan's assumption that it was one too many is not unreasonable. In the middle of the fight, Riggleman could be seen mouthing the words "one time" to Florida manager Edwin Rodriguez, indicating the number of attempts he felt the Marlins were entitled to. ("We decide when we run," Riggleman told the Sun-Sentinel. "The Florida Marlins will not decide when we run.")

"I understand they had to get me back a little bit," said Morgan to the media. "It's part of the game ... I guess they took it the wrong way. He hit me the first time, so be it. But he hit two other of our guys?" (Volstad did indeed hit three batters on the day.) "All right, cool. But then he whips another one behind me, we got to go. I'm just sticking up for myself and just defending my teammates. I'm just going out there and doing what I have to do."

Doing what he had to do, of course, is up for interpretation. Saying that there's a case to be made for his viewpoint on one of the incidents leading up to the fight is far from saying that the guy has not been wildly, unassailably, dangerously out of line for the better part of a week.

Guys like Manny Ramirez and Alex Rodriguez can flaunt the unwritten rules at their discretion; their jobs are safe, so long as they continue to produce.

When it's a leadoff hitter with a .317 on-base percentage, who led the league in being caught stealing last year and is on the way to doing it again, the margins are considerably tighter.

Watch out, Nyjer Morgan. There aren't many people in your corner right about now.