JAWS: A look at the Pre-Integration Hall of Fame ballot, Part II

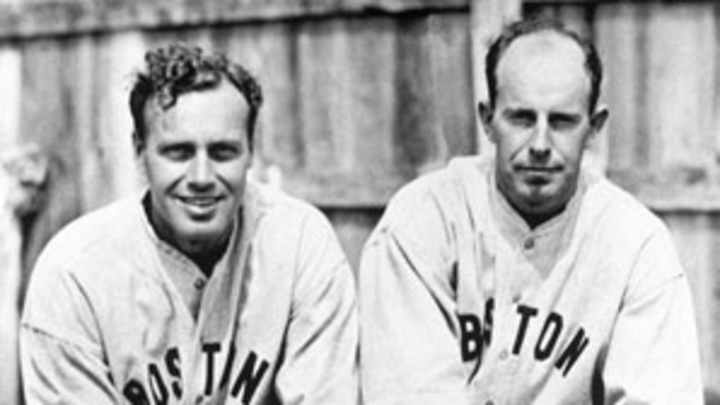

Rick Ferrell (left) is already in the Hall of Fame; his brother Wes (right) may join him this year. (MLB Photos via Getty Images)

Earlier this week, I kicked off my analysis of the Hall of Fame's Pre-Integration Era ballot, a slate of 10 players, managers, umpires and executives whose most significant career impact took place before 1946, but who for one reason or another have been bypassed by the BBWAA and Veterans Committee voters over the years. Among those who will be voted upon by a 16-member panel of former players, executives, writers and historians, the cases of the three hitters and three pitchers on the ballot lend themselves to analysis using the Jaffe Wins Above Replacement Score (JAWS) system to compare them to the already-enshrined players at their positions using both career and peak (best seven seasons) WAR totals.

Advanced metrics such as WAR are a handy tool for such an endeavor, providing a firm basis for comparison among a group of players whose careers took place during a time when the game’s rules were still evolving, with offensive levels fluctuating in conjunction with frequent changes, making their raw statistics harder to parse. JAWS is a big help in such matters, though it can’t incorporate everything that goes into a player’s Hall of Fame case. It makes no attempt to account for postseason play, awards won, leagues led in important categories, career milestones and historical importance, much of which is better handled via the Bill James Hall of Fame Standards and Hall of Fame Monitor metrics.

I'll skip a rerun of the longer preamble explaining the deeper reasons for the creation and use of JAWS — readers of this space will get enough of that in the coming weeks — and instead turn to the pitchers on the ballot (for my thoughts on the three hitters, click here):

Player | Career | Peak | JAWS | From | To | W | L | ERA | ERA+ | IP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tony Mullane | 61.5 | 47.0 | 54.3 | 1881 | 1894 | 284 | 220 | 3.05 | 117 | 4531.1 |

Bucky Walters | 52.0 | 42.1 | 47.0 | 1931 | 1950 | 198 | 160 | 3.30 | 116 | 3104.2 |

Wes Ferrell | 57.2 | 52.0 | 54.6 | 1927 | 1941 | 193 | 128 | 4.04 | 116 | 2623.0 |

Avg HOF SP | 67.9 | 47.7 | 57.8 |

Wes Ferrell

The younger brother of Hall of Fame catcher Rick Ferrell is arguably the one more qualified to be enshrined. The long-running joke is that the hearing aids might not have been working all that well on the wintry 1984 day when the Veterans Committee met and voted in the seven-time All-Star backstop — who ranks just 45th among catchers in JAWS, and last among the Hall of Fame ones — thinking they were voting instead on his brother, the ace hurler. In his heyday with the Indians, Wes Ferrell was regarded as the equal of the great Lefty Grove, and thanks to some award-winning research by SABR scholar Dick Thompson, we know that at his peak he faced much tougher competition than Grove, who consistently feasted on the league's lesser teams. Alas, a researcher named Chris Jaffe (no relation) has also shown that Ferrell was rather poorly deployed in his later years with the Red Sox, and that the overall quality of his opponents wasn't particularly extreme.

Most of Ferrell's big years were with the Indians, for whom he pitched from 1927 (though only three games before 1929) through 1933, tallying four straight 20-win seasons from 1929-1932. He was sold to the Red Sox in 1934, at a time when new owner Tom Yawkey was in the habit of buying over-the-hill players; a 34-year-old Grove put up a 6.50 ERA for Boston that year. From 1929 through 1936, Ferrell won 161 games with a 3.72 ERA, which in that high-scoring era was still 28 percent better than the park-adjusted league average. He finished second in the AL MVP vote in 1935 on the heels of a monster 10.4-WARP season in which he won 25 games while pitching 322 1/3 innings of 3.52 ERA ball (34 percent better than league average) and hit an insane .347/.427/.533 with seven home runs in 179 plate appearances as a pitcher. On that note, Ferrell was an outstanding hitter who batted .280/.351/.446 with 38 homers for his career (his brother hit just 28, and had lower a batting average and slugging percentage), numbers that chip away at the fact that his 4.04 ERA would be the Hall's high were he to gain entry. The 12.1 WAR he generated with the bat — including over 150 pinch-hitting appearances, and a brief stint in the outfied — ranks fourth among pitchers, and they're about 11 wins more than the average Hall of Fame hurler.

Ferrell's case is hurt by the fact that he didn't accomplish much after age 28, his 10th big league season, largely due to arm troubles. Along with his brother, he was traded from the Red Sox to the Senators in June 1937, and while he finished out the year in strong fashion, he was terrible in 1938 (6.28 ERA). He underwent surgery to remove bone chips in his elbow after that season, but was a virtual nonentity on the major league scene thereafter, making just eight appearances for three teams across three seasons. He went down to the low minors, hitting 20 homers as an outfielder/manager for the Leaksville-Draper-Spray Triplets of the Class D Bi-State League in North Carolina and thereafter bouncing around the minors.

Ferrell's career WAR falls well short of the standard for the average Hall of Fame starting pitcher, but his peak score is well above, ranking 27th all-time ahead of the peaks of Juan Marichal, Gaylord Perry, Fergie Jenkins, Warren Spahn, Bob Feller, Bert Blyelven and even Sandy Koufax. By equally weighting career and peak values, the JAWS system was constructed in a way to handle such cases, with a sort of sliding scale mentality: "If your peak was this high, your career must be this big to ride the Cooperstown Express." Even so, I've always advocated further consideration before dismissing the high-peak/short-career types as simply below the standard, because being deprived of the undignified denouements to otherwise impressive careers can be a blessing. Thus I can see a reasonable argument for Ferrell's inclusion, just as I did four years ago.

Tony Mullane

Born in Ireland like many a 19th century player, Mullane played at a time when the game's rules were still in flux. During his career, the pitching box (not a mound) was located only 45 or 50 feet away from home plate; it wasn't moved to 60-feet-6-inches away until 1893. A pitcher could take a short run before throwing, and didn't have to throw nearly so hard, and a batter could call for a high or a low pitch up until 1887. When Mullane debuted in 1881, it was eight balls for a walk, while in 1884 that was reduced to six, and 1887 to five; the number of strikes for an out was temporarily increased to four in the latter year.

Amid all of that madness, "The Apollo of the Box" put up some staggering innings totals for the Louisville, St. Louis, Toledo and Cincinnati entries in the American Association, where after a brief National League stint in 1881 he spent seven of the next eight seasons (1882-1889 except 1885). His career high was 567 in 1884, when he made 65 starts, completed 64 games, and struck out 325, finishing with a record of 36-26, but amazingly, none of those totals led the league. He won 30 or more games in five consecutive seasons, and ranked in the league's top five in wins five times and in ERA four times; he cracked the top 10 in innings and WAR eight times apiece. At the height of his career, he missed the 1885 season due to a suspension involving an attempt to jump to teams and leagues that soon folded. Had he not missed that season — or sat out half the 1892 season protesting pay cuts that took place after the NL absorbed four AA teams and thus had a major league monopoly — he'd have likely topped 300 wins.

Mullane gained some renown for briefly experimenting with switch-pitching, becoming the first major leaguer to throw with both hands in a single game in 1882, and doing so on at least one other official game occasion and perhaps several exhibitions. Though not much of a hitter even for the time (.243/.307/.316, 6.6 WAR) he did play over 200 games at other positions around the field as well. After moving back to the NL with the Red Stockings/Reds in 1890, he didn't adjust well to the rapidly modernizing game, at least at the major league level; in one 1894 NL game, he set a record by allowing 16 runs in the first inning. After that season, he spent a few more years knocking around the minors, mostly in the Western League, which soon evolved into the modern American League.

Mullane's JAWS score is a hair behind that of Ferrell, but neither that nor his career or peak components tops the standards. He's within 0.7 — one run per season, a margin that's subject to the slightest change in underlying assumptions — on the latter, and one can surmise that he would have crossed that threshold had his career not been interrupted for something that was all-too-common in an era where rival leagues raided each other's rosters, and owners acted unscrupulously; his 12.8 WAR in in 1884 was a career high, though he was never anywhere close to that valuable again. It may be splitting hairs given how close their scores are, but Mullane's case beyond the single-number-endpoint of the process isn't as strong as Ferrell's, particularly when one considers that the AA almost certainly was an easier league than the NL. If I could only pull one of the two out of this gray area, it would be Ferrell.

Bucky Walters

Walters was a converted infielder who spent most of his first four seasons in the majors with the Braves and Red Sox (1931-1934) playing third base, and he continued to make cameos there through 1937, though his hitting (.243/.286/.344, 7.7 WAR) wasn't much to write home about. Sold to the Phillies in mid-1934, when he was 25 years old, he began his conversion to the mound, and learned to throw a slider from Hall of Famer Chief Bender.

Jay Jaffe is a contributing baseball writer for SI.com and the author of the upcoming book The Cooperstown Casebook on the Baseball Hall of Fame.