A Run to Remember

Fred Taylor recently led a crucial team meeting to address the Jacksonville Jaguars' shower habits. He stood in the front of the locker room, a portrait of perfect hygiene. The running back said that he wakes up every Sunday exactly five hours before a 1 p.m. kickoff, walks into his bathroom, lays out his towel, turns on the water and finds just the right temperature on the dial, a tad warmer than warm. Then he turns off all the lights.

"I stand in the shower with my eyes closed and the water falling down on me, and I imagine this great white light," Taylor says. "Then I see our team on the field. I think about every play we are going to run, how each one is going to work. It's like I play the whole game right there in the dark. And it's always the perfect game."

He sees himself taking a handoff and bulldozing 300-pound defensive linemen for a first down. On the next play he slides out of the backfield and snags a swing pass on the run. On the next he gets a pitch, shakes a linebacker and dusts a safety on his way to the end zone. Only after the Jaguars have won the game does Taylor step out of the shower and turn on the lights, finally ready to play.

Taylor told teammates about his ritual not because he wanted them to mimic it but because he wanted them to share his vision. He does not know how many Jaguars are now showering in the dark -- "It's not like we do it together or anything," he says. He only knows that they are playing exactly the way he imagined they could.

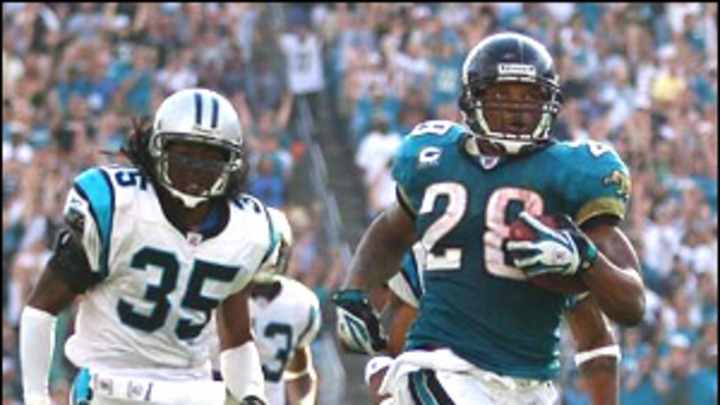

Jacksonville ran down the Carolina Panthers 37-6 on Sunday, improving its record to 9-4 and bolstering its case for an AFC wild-card berth. For the first time since 2004, Taylor had a third consecutive 100-yard game, capping his 132-yard day with a career-best 80-yard touchdown dash in the fourth quarter. The Jaguars are built for the playoffs: First quarter or fourth, they hand the ball to Taylor or fellow running back Maurice Jones-Drew and push defenders out of the way.

Taylor has been a Jaguar for 10 of the team's 13 years in the league. During that decade he has become known mainly for his balky body parts: shoulder, hamstring, thigh, ankle, foot, groin, back, hip, knee and other knee. Impatient fans have called him Fragile Fred. So what should they call him now that, at 31, he has 10,457 career rushing yards and ranks 17th on the alltime list of running backs in yards and ninth in combined rushing and receiving yards per game? Future Hall of Famer, perhaps.

At the very least Taylor is an overlooked star. Of the top 49 rushers in NFL history, he is the only one never to have made the Pro Bowl. He is not even the most celebrated running back on his own team, often overshadowed by his supposed understudy, Jones-Drew. But, as Jones-Drew himself puts it, Fred Taylor "is the Jaguars."

The Jacksonville locker room is unlike any other in the NFL. The stereo blasts Rick James. Half the defense sings along to Mary Jane. Wideout Reggie Williams gyrates next to a laundry basket. Brett Hawkins gives fellow defensive end Kenny Pettway a face full of baby powder. And a shirtless intern parades around in cutoff black spandex shorts, dark sunglasses, a construction helmet and a giant grin.

"So it's not like this in New England?" defensive end Bobby McCray asks. With baby powder floating all around him, Taylor does his best impersonation of a Patriot. He sits silent and stone-faced at his locker, nose buried in a laptop computer. He seems oblivious to the powder and the spandex, but more likely he is recording it all for posterity. "I like to take notes," he says, "for my book."

There may not be an audience for his memoir, but he certainly has the material. Taylor was born in Belle Glade, Fla., to a mother who was 15. He thought of her as his sister, his grandmother as his mom. The family lived in the upstairs of a duplex apartment, five people crammed into two bedrooms. In the summer the teenage Taylor worked in the sugarcane fields. "The mosquitoes," he says, "were big enough to pick you up and take you away."

He went to the University of Florida, where he played on the 1996 national championship team and was suspended twice for misdemeanors. Once he was part of a group that ordered pizza with a stolen credit card. He was also found with a backpack that had allegedly been stolen by a teammate. "Those incidents -- they did not speak to his character," says Carl Franks, Taylor's position coach at Florida and now the running backs coach at South Florida.

Taylor arrived in Jacksonville in 1998 as a first-round pick with four gold teeth and an agent named Tank. But to call William (Tank) Black an agent is to understate his relationship with Taylor. He was a father figure to a player who barely knew his father. So when Black was tried in U.S. District Court in Gainesville, Fla., in 2002 for allegedly swindling millions from NFL players -- including $3.1 million from Taylor -- more than money was at stake. Testifying for the prosecution, Taylor choked up on the stand. "I trusted him with my life," he said of Black, who was convicted on four conspiracy counts and sentenced to five years in prison.

It took awhile for Taylor to recognize just how much Black had taken from him. Taylor had endured interviews with the police, the FBI, a grand jury and the Securities and Exchange Commission in connection with the Black investigation. Looking back, he believes that his many football injuries were at least partly due to all the stress he suffered during that ordeal.

"For the longest time Fred wasn't allowed to talk about this," says Jerald Ingram, the former Jaguars running backs coach who has the same job with the New York Giants. "Finally, one day he came to me and let it out. He was heartbroken. He felt betrayed."

The Black case changed him. Today Taylor has four children, a wife and no gold teeth. He drives a Dodge pickup and lives in a two-story house. By Nov. 30 the house was decorated for the holidays. A wreath hung on the front door. A Christmas tree stood in the living room. Stockings dangled from the fireplace. When Taylor sees lights left on around the house, he shakes his head. He makes $5 million a year and worries about the electric bill.

Black is scheduled to be released next May, and Taylor thinks about what it would be like to see him again. "I'd probably thank him," he says. "He opened my eyes. He made me a lot more careful about everything."

Taylor started to protect his body as well as his bank account, realizing they are one and the same. Early in his career he was a regular on the nightclub scene. In the off-season he rarely worked out until a month before the start of training camp. Seeing where that regimen had led him, he devised a new routine. He would be at the Jaguars' facility every morning by 6:30. He hired a masseuse to rub him down twice a week. He tried acupuncture. He consulted a nutritionist. And perhaps most important, he sought out psychologists Chad Bohling and Trevor Moawad.

Moawad meets with Taylor every other week and gives him something to read and something to watch (usually a personal highlights video intercut with inspirational movie clips, NFL Films footage and motivational messages). Taylor downloads the videos onto his iPod so he can watch them at his locker before games.

Lounging on the leather sofa in his living room, Taylor cues up his favorite piece of video. He smiles as if he's about to show off his greatest runs. Instead the iPod plays his most painful ones. There he is grabbing his groin, clutching his hamstring, holding his elbow, taking a vicious shot to his left knee. "Pat Tillman gave me that one," he says. "Pat Tillman -- I'll never forget it."

The sound track is of Rocky Balboa giving a speech in the most recent Rocky sequel: "The world ain't all sunshine and rainbows. It is a very mean and nasty place. It will beat you to your knees and keep you there permanently if you let it. You, me or nobody is going to hit as hard as life. But it ain't about how hard you hit, it's about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward, how much you can take and keep moving forward."

On Nov. 11 at Tennessee, Taylor was 13 yards from the 10,000-yard career total that is the benchmark for great running backs. He told his linemen, "I'm not going to juke anybody. I'm just going to run people over." For years Taylor was a little back in a big back's body. Though the Jaguars' media guide lists him at 6' 1", 228 pounds, with his cuts and shimmies Taylor reminded fans of smaller jitterbugs such as Barry Sanders.

But when Taylor took the handoff that day in Nashville, he did not try to run around Titans safety Chris Hope. He exploded through him, carrying Hope along for a 15-yard gain and the milestone. Tennessee fans, some of whom had been rooting against Taylor since his SEC days at Florida, stood to salute him. You could almost hear patrons at sports bars around the country asking, Fred Taylor has 10,000 yards?

"He's not Fragile Fred anymore," left tackle Maurice Williams says. In his first four years, Taylor missed 24 games. In his last six seasons he has missed only eight. In the locker room at Tennessee, as players chanted "Fred-die!" and "Uncle Fred!", Jaguars owner Wayne Weaver threw an arm around Taylor and announced, "This guy has been the heart and soul of this football team for a lot of years."

Last spring, when Taylor was entering the final year of his contract and seeking an extension, the Jaguars easily could have handed the job to Jones-Drew. But they couldn't imagine life without Taylor. So they added three years to his contract, believing that Jones-Drew could help prolong Taylor's career. He now plans to play through 2010.

He has become an unlikely club leader. When he talks to his teammates after practice, he does not ad-lib. He recites a speech he has written on a sheet of paper, tucked into his waistband and carried throughout the session.

After Jacksonville drafted Jones-Drew in the second round in 2006, Taylor arranged a meeting with the rookie in the locker room. "I'm here to learn from you," Jones-Drew said.

"Then I'm willing to teach," Taylor replied. The two have become so close that Taylor's wife, Andrea, sometimes cooks dinner for Jones-Drew during the season.

Fred Taylor first spotted Andrea Barnett through his camcorder on a vacation in Cancún, Mexico, in 1999. He was filming, as he says, "all the scenery." He spent two minutes taping her from afar but never approached her. When he got back to Jacksonville and watched the footage, he recognized a woman standing next to Andrea. She was a former girlfriend of Tampa Bay Buccaneers linebacker Derrick Brooks. Taylor contacted Brooks and begged him to set him up with Andrea. Three years later Taylor proposed to her, though he could not bend down on one knee because his groin was so sore. Even in his personal life he was playing hurt.

Sometimes Taylor wonders what his career statistics would be if he had not missed 32 games due to injury. He might have a couple thousand more yards by now. But those who understand the art of rushing still appreciate his stylish bursts. Last off-season, while Taylor dined with friends at a Miami steak house, O.J. Simpson approached his table. "I love to watch you run," Taylor says Simpson told him.

Starved for a chance to play in the spotlight, Taylor constantly monitors the playoff race, calculating tiebreakers and breaking down potential matchups. He knows what an extended playoff run would mean, both to himself and the Jaguars. They could finally grab a little of the love that always goes to the Colts and the Patriots.

As he stands outside his house, he visualizes a showdown with New England, a berth in the Super Bowl at stake. He can hardly contain his excitement. Then he excuses himself to go inside. Maybe it's time for a shower.

Lee Jenkins joined Sports Illustrated as a senior writer in 2007. Since 2010 his primary beat has been the NBA, and he has profiled the league's biggest stars, including LeBron James and Kevin Durant.