The Color of Money

This month marks the 40th anniversary of a five-part series in SI that remains among the most powerful and socially significant pieces ever to appear in the magazine's pages. The Black Athlete - A Shameful Story (SI, July 1, 1968) explored the experience of African-Americans in sports with depth and detail -- often stark, saddening detail -- that much of white America had never before confronted. Senior editor Jack Olsen and a network of correspondents spent four months interviewing hundreds of athletes, coaches and educators, both black and white, and came away with a portrait of the "Negro athlete," to use the term more common to those times, as isolated, exploited and dehumanized, with an anger at that treatment that was boiling just beneath the surface.

It's easy to be horrified by some of the attitudes expressed in the series, yet comforted as well by how enlightened sporting America, 40 years later, looks in comparison. The first quote in the opening story is: "In general, the nigger athlete is a little hungrier, and we have been blessed with having some real outstanding ones. We think they've done a lot for us, and we think we've done a lot for them." Those were not the words of some shock jock or blowhard pundit. They were from George McCarty, then the athletic director at Texas-El Paso. We can read that statement secure in the knowledge that if it had been uttered today, McCarty would have gone the way of Jimmy the Greek, Al Campanis, Rush Limbaugh and Don Imus -- vilified, pink-slipped and immediately inducted into the Racial Stupidity Hall of Fame.

That's because when blatant racism arises in 21st-century American sports, we can barely contain our excitement. We stone the offenders in the town square, not so much to make an example of them but to reassure ourselves that we are no longer the culture that Olsen wrote about 40 years ago. When someone uses taboo words or images -- when a broadcaster offhandedly jokes about lynching in reference to Tiger Woods or a radio personality describes black women basketball players as "nappy-headed hos" -- it's like a fastball down the middle. We are almost gleeful in our rush to punishment, eager to prove that we don't stand for that sort of thing anymore.

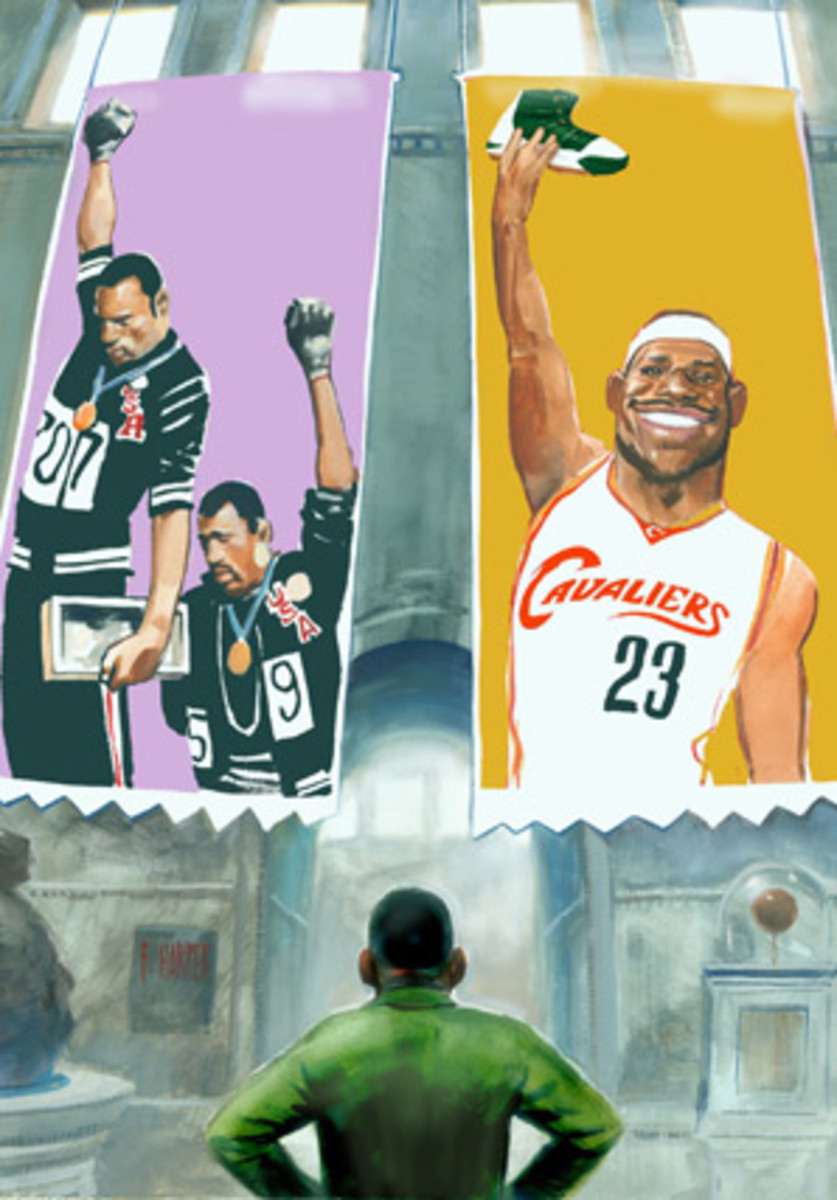

But matters of race aren't always so cut-and-dried, and when they get less obvious, the culture grows clumsier. No longer outcasts once they're away from the field or court, black athletes are now idolized by mainstream society -- up to a point. Corporate America makes millions by capitalizing on white suburban kids' desire to rock the latest LeBron James sneakers and their dads' urge to go to games decked out in LaDainian Tomlinson jerseys. Teams pump hip-hop through the loudspeakers at arenas and profit from the cachet that comes with having rap artists sitting courtside.

Yet those same corporate entities want to keep that culture at arm's length, lest it get too threatening to the paying customers. Thus we have the airbrushing of Allen Iverson's tattoos in an NBA-produced magazine, and the league's dress code, which makes sure the players won't look too much like some of the musical artists the league otherwise embraces. You may call it racist and hypocritical; they call it good business.

America today likes its racism overt and indisputable, otherwise the tendency is to deny its existence. Former Mets manager Willie Randolph learned as much a few weeks ago, before his firing. Randolph, the first black manager of a New York baseball team, had the temerity to suggest that the public's dissatisfaction with him might be tied in part to his race, a contention that was dismissed in most circles as little more than whining. The truth was that while race wasn't at the top of the list of reasons that fans were pushing for Randolph's firing, it wasn't at all ridiculous to suggest that it had a place somewhere on the roll call. But if race isn't clearly the main factor, to many it must not be a factor at all.

This isn't to say that blacks in sports haven't made great strides in the last 40 years. If nothing else, we are less likely to take the wide range of African-American men and women in sports and treat them as one monolithic entity. There is no Black Athlete, but a variety of black athletes, some of them as different as Grant Hill and Adam (Pacman) Jones.

Other signs of progress aren't hard to spot. Olsen, who died in 2002, wrote of black athletes in college who were demoted or cut for socializing with white girls. Flash forward to the U.S. Open last month, when Tiger Woods's blonde, blue-eyed wife, Elin, handed him their baby daughter and a national TV audience witnessed it without causing the slightest stir.

Black professional stars like baseball's Frank Robinson watched in 1968 as they were passed over for endorsements in favor of white players. Today Michael Jordan ranks as the greatest athlete-pitchman of all time, and everyone wants to be in Charles Barkley's Fave 5. Stanford's Gene Washington told Olsen that he voluntarily switched from quarterback to wide receiver because in those days he knew that there was no future in the NFL for a black QB. These days black quarterbacks not only get their shot, but like the Raiders' JaMarcus Russell, they can also be the No. 1 pick of the draft.

As for exploitation, that goes both ways. Colleges still are sometimes guilty of using black athletes' bodies with little concern for their minds, but some athletes use colleges as nothing but a necessary, and brief, way station on the way to the pros. You saw a few of them, one-and-done players such as Derrick Rose, Michael Beasley and O.J. Mayo, walk across the podium at the NBA draft last week.

If Olsen had undertaken the same project today, it's unlikely he would have been able to settle on anything approaching a universal portrayal of the state of the black athlete. The culture is more complicated, and perhaps the athletes who populate it are too. But maybe we've advanced enough in the last 40 years that he would change the title from A Shameful Story to a Hopeful one.