Jazz's Kirilenko revives career -- thanks to a seat on the bench

But it hasn't always been a sweet one. Really. There has been a seven-year relationship with coach Jerry Sloan that can be charitably characterized as rocky. There has been a made-for-TV meltdown after a playoff loss in 2007, when Kirilenko wept openly for the cameras. There has been controversy after he threatened to walk on his contract and return to his motherland. And there have been two years of declining production.

"At times, things have been rough," says the 27-year-old Kirilenko.

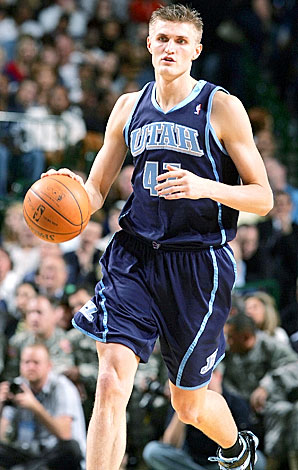

But just when the spindly, 6-foot-9 Kirilenko seemed about to snap, he has been rejuvenated by ... a demotion. A preseason ankle injury to sixth man Matt Harpring left Sloan worried about the strength of his second unit, so he gave C.J. Miles the starting small forward job and made Kirilenko a sub.

"We needed someone to give us energy off the bench," says Sloan. "Andrei has done that. Do I think he'd like to be a starter? Yes. But he's done a great job for us in this role."

Now the NBA's highest-paid reserve, Kirilenko is playing some of the best ball of his career, averaging 13.0 points, 6.3 rebounds and 1.6 steals -- up from 9.7, 4.7 and 1.1 as a starter over the last two years.

Pigeonholed as a small forward in a first unit that is strong at every position, Kirilenko has filled in everywhere but center with the second team, creating mismatches all over the floor. His ball handling allows him to ignite fast breaks, and his size makes him effective around the basket. Last week he averaged 17.5 points and 7.0 boards in victories over the Suns and the Bucks, and he had 10 assists in a defeat of the Grizzlies.

"Coming off the bench, I get to see the rhythm of the game," he says. "I've always been more of an analyst. I like to watch where players like to go on the floor. And when I get in, the other team is usually tired and I have fresh legs."

While his offensive game needed a boost, Kirilenko's D never left him. With his 7-4 wingspan and superior reflexes, he can block a shot even when his hands are dangling by his side when the ball is released. Late in the fourth quarter against Phoenix, Kirilenko rejected two shots from Shaquille O'Neal on the same possession. Both times the ball had already left Shaq's fingertips when Kirilenko made his move. (With 3.3 per game in 2004--05, Kirilenko became the shortest league leader in blocks since it became an official stat in 1972.) And he's not just a shot swatter. With Utah clinging to a late four-point lead against Milwaukee, Kirilenko poked the ball away from Bucks point guard Ramon Sessions and took it the length of the court for a game-sealing dunk. What was special about that steal -- his fifth of the night -- was that it came during a dribble handoff. As Sessions gave the ball to Richard Jefferson, Kirilenko slid his arm between the two and knocked the ball free.

"Did he just do that?" marveled a scout watching the game. "He's Rope Man. He can get those arms in the smallest of spaces."

By settling into his new role, Kirilenko has eased any potential tension with Sloan. That's not to say there isn't any tension. After Kirilenko uncharacteristically blew a defensive assignment against the Suns, he and Sloan could be seen shouting at each other from opposite ends of the court. And after watching Kirilenko launch an ill-advised jumper early in the shot clock later in the game, a visibly agitated Sloan spun and stormed back to his seat on the bench.

"Coach doesn't like those kinds of mistakes," says Kirilenko, a toothy grin creeping onto his face. "I don't blame him for being mad about that."

Says Sloan, "Andrei and I are fine. I don't need my players to like me. I need them to play for me."

***

Kirilenko says he prefers to bottle up his feelings until they "explode out of him," so he is quick to downplay any rift with the 66-year-old Sloan, who recently became the first coach to reach 1,000 wins with the same team.

"Jerry is a legend," says Kirilenko. "He is the face of the Jazz organization. He has his style, and it works. It has worked for me too."

Kirilenko's wife, Masha, though, has her own opinions. A singer (the video for her 2002 hit single, Saharniy -- which translates loosely to sugary -- quickly rocketed to No. 1 on MTV Russia) with brains (she holds an undergrad degree in foreign languages and a masters in art) and ambition (in addition to running her husband's charitable foundation, she recently opened her own clothing boutique), Masha rarely misses a home game. When Andrei is on the bench, she'll mouth -- in Russian -- anything from I love you to postgame dinner plans. When Andrei is in the game, he'll often turn to her and shout in Russian after a significant play. They're not quite ready to replace Doug and Jackie Christie as the NBA's first couple of idiosyncratic communications, but Masha is, safe to say, a full partner in Andrei's career.

Relaxing at the Kirilenkos' spacious, modern Salt Lake City home, Masha's eyes grow wide when told that Sloan didn't care whether his players liked him.

"Does he care whether their wives like him?" she says.

Andrei turns and mutters something to her in Russian.

"He doesn't like me to talk about that," says Masha.

"It's not that I don't like Jerry," says Andrei. "He's a good person. He's just from an older generation that treats players like kids. Let's say your boss comes to you and says, 'Hey, son. Come here'. And you look at him like, What did you call me? It doesn't hurt your feelings, but it doesn't feel comfortable."

Says Masha, "The guy remembers a time when he was driving a '65 Chevy. To him, Andrei will always be a kid."

A first-round pick in 1999, Kirilenko arrived in the U.S. two years later, fresh from CSKA Moscow. Despite his seemingly fragile 220-pound frame he quickly became one of Utah's most consistent and versatile players. The anti--Karl Malone -- the Mailman made his living running the pick-and-roll and banging in the low post -- Kirilenko is rarely used as a screener and can score from almost anywhere on the floor. He played in all 82 games in his first season, was an All-Star by his third and made the All-Defensive first team in his fifth.

The Kirilenkos' issues with Sloan first developed during 2006-07, when point guard Deron Williams and power forward Carlos Boozer emerged as Utah's primary options. That squeezed out Kirilenko, who saw his scoring average decline from 15.6 in '05-06 to 8.3 and his playing time drop by 10 minutes per game. In closed-door meetings Sloan advised him to keep playing defense while Kirilenko asked for a bigger role in the offense.

"I was really frustrated," says Kirilenko. "I didn't know how Coach wanted me to play. I didn't know what to do on the floor. I played hard defensively, but I was lost on the other end."

Rock bottom came during the first round of the playoffs. After sitting on the bench for the final 17 minutes of Utah's Game 1 loss to the Rockets, Kirilenko began sobbing as he talked to the press at practice the next day. "I have no confidence," he told reporters. "None." A horrified Masha could barely watch. The following morning she flew to Houston and found her husband alone in his hotel room, inconsolable.

"The thing that you have to realize about Andrei," says Masha, "is that he is impossible to get upset. I can't do it. So when I saw him like that, I knew something was seriously wrong."

After the season the couple returned to Moscow, where Kirilenko led the Russian national team to the European championship and was named MVP of the tournament.

"I found out there was nothing wrong with my game," he says. "I was still the same player."

Emboldened by his success, Kirilenko began to lash out. He complained to the Russian press that the Jazz treated him like a rookie instead of a franchise player. He praised Russia's coach, David Blatt, in his blog for helping him "realize a dream" while attacking Sloan for constantly reminding players of their exorbitant contracts and harping on their mistakes. To top it all off, he demanded a trade and threatened to walk away from his contract and stay in Russia if it didn't happen.

"We didn't want to go through that again," says Masha. "That was the worst year of my life. I cried every day."

The trade never materialized. Kirilenko reported to camp (he blamed the media for blowing his remarks out of proportion), and after a clear-the-air meeting with Sloan and general manager Kevin O'Conner, he stepped right back into the starting lineup.

"There was a frustration on our part and a frustration on Andrei's part," says O'Conner. "He told us what he had to do to get over the hump, and we tried to give him what he needed."

Kirilenko's numbers ticked up last year, and, more important, he and Sloan appeared to bury the hatchet -- or at least learned to coexist.

"If you have two competitive guys, there are going to be disagreements," says Bucks coach Scott Skiles. "Too much is made of that. Nobody wants a team full of patsies who won't voice their opinions."

***

Sitting at his kitchen counter with his wife by his side, Kirilenko looks to be at peace. His family is happy -- when asked his favorite place, the Kirilenkos' seven-year-old son, Fedor, says, "America" -- in part because he and Masha have decided to leave the basketball talk in the gym.

"We used to talk about it all the time," says Andrei. "It was 24/7. Now we try to focus on other stuff." He still thinks about playing in Russia, but not anytime soon. "When my contract is up, I'd like to go back," he says. "I want my country to see me play before I am too old."

For now, life is a sweet dream. Really. Sure, he's a little more jaded -- "It's hard to totally forget all the stuff that happened," he says -- but he's usually wearing the grin that Masha fell in love with nine years ago.

"I've seen Andrei happier two times," says Masha. "When he made the All-Star team and on our honeymoon. He just wants to help his team. That's the only thing that matters to him."