Twenty years ago, an earthquake shook a Bay Area World Series

In the middle of the night, when he was searching for peace, Dave Stewart would go walk among the bodies.

Stewart didn't know who was dead and who was alive. It was not his place to ask. He was there to bring food, clothing and water to the workers by the Nimitz Freeway in the Oakland neighborhood where he grew up.

This was the first place he had gone when the earthquake stopped the 1989 World Series -- his World Series, between his team, the A's, and the team he watched as a kid, the Giants. Stewart was known throughout baseball for his community involvement; he ran an anti-drug program in Oakland. But he did not go to Oakland to help -- not at first.

He was looking for his sister.

Brenda Stewart worked as an underwriter at The Hartford in San Francisco, and her daily drive home took her over the Bay Bridge. Brenda had been commuting home when the earthquake hit. But she had taken the train.

Brenda got off at the Bay Area Rapid Transit stop in West Oakland and pulled her car out of a nearby garage. The parking attendant told her there had been an earthquake, but so what? This was Northern California. Some places got snow; the Bay Area got earthquakes.

Brenda tried to drive to her home at 18th and Cypress Streets when she saw the road was blocked off. She looked up and saw that the Cypress Street viaduct had collapsed.

Dave Stewart showed up at Brenda's house later that night. The drive from Candlestick Park, normally 20 minutes, had taken five hours because a portion of the Bay Bridge had collapsed. Stewart was still in his baseball uniform when he saw his sister was alive.

That night, he drove to his home in nearby Emeryville, then came back with food and other supplies. He kept coming back every day.

A lot of people who lived in the neighborhood had temporarily moved out, either because their homes were badly damaged or because they could not handle the stench of death. But Stewart kept coming back. He had to come back.

Sometimes he would lie in bed at two or three in the morning, unable to sleep, and he would get dressed and drive down to Oakland, to confront the misery that consumed his friends, his teammates, most everybody he knew. Once he saw it up close --- once he helped a little bit more --- then, and only then, could he go home and fall asleep.

On the night of Oct. 17, Stewart, the rest of the A's and the San Francisco Giants had been at Candlestick Park, getting ready for Game 3 of the World Series. It was everything they had ever wanted out of sports. And then, suddenly, it meant nothing.

*****

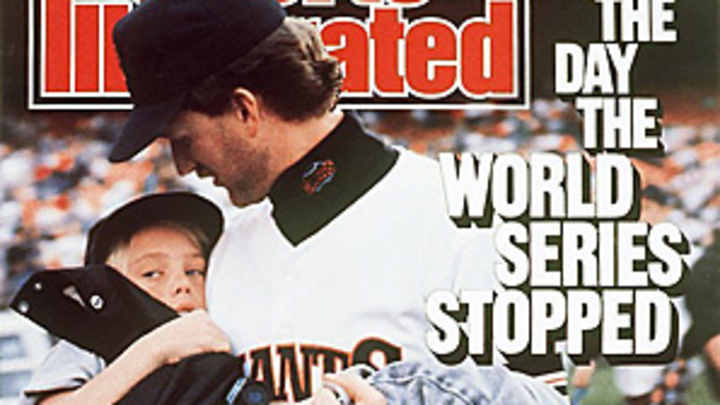

Twenty years ago this month, San Francisco and Oakland hosted one of the most unusual sporting events in American history: a rare moment of civic triumph (not one, but two hometown teams in the World Series) interrupted by unfathomable catastrophe (the Loma Prieta Earthquake, one of the worst natural disasters ever to hit the United States).

They had already been calling it the Bay Bridge Series for a week when the earthquake hit. The nickname was a natural. The Bay Bridge connected San Francisco and Oakland, and this was the modern-day equivalent of a Yankees-Dodgers Subway Series.

In that comparison, the A's were the Yankees: the dominant outfit, expected to not only contend but win it all. Before the playoffs began, a billboard went up on the east side of the bridge that read "Oakland Welcomes The World," with space left so they could fill in the word "Series" later. Oakland had been planning for this moment since the year before, when the Dodgers had stunned the A's in the World Series.

The A's easily dispatched the Blue Jays in five games in the American League Championship Series, thanks in part to Jose Canseco's mammoth home run in Game 4, which landed in the fifth outfield deck of the sparkling new Skydome. That home run seemed to crystallize the dominance of the A's: they did not just beat you, they left you awestruck, and they seemed to have power they didn't even need.

After Canseco rounded the bases, he met fellow Bash Brother Mark McGwire at home plate.

McGwire: "You didn't really get all of that, did you?"

Canseco: "No, I kind of popped it up."

Who could compete with seemingly superhuman strength? The Giants? In 1988, while the A's were marching to the World Series, the Giants had finished in fourth place in their own division, and the year was even worse than the season: starting pitcher Dave Dravecky was struck with cancer and shortstop Jose Uribe's wife had died during childbirth.

But here were the 1989 Giants, spurred by manager Roger Craig (and his "Humm Baby!" rallying cry), inspired by Dravecky (who returned to pitch two games in August) and led by first baseman Will Clark and National League MVP Kevin Mitchell, who hit 47 home runs that year, 14 more than McGwire.

The Giants won 92 games to take their division, then won the NLCS because they were playing the Cubs. In the celebration afterward, Dravecky broke his arm again. The cancer had returned. His career was over.

In the days leading up to the Series, Bay Area vendors sold hats that featured half of the Giants' interlocking "SF" and half of the A's logo. Commemorative T-shirts touting "Baysball" went for $20.

San Francisco Mayor Art Agnos proudly told The New York Times that "we will be the media capital of the world for a couple of weeks," and Oakland Mayor Lionel Wilson said, "A lot of people, even in the Bay Area, don't know anything about Oakland. This is a tremendous opportunity to show off."

The World Series began with a moment of silence -- for the late commissioner, Bart Giamatti, who had died suddenly of a heart attack at age 51 just six weeks earlier. The A's then won the first game in Oakland behind a shutout by Stewart. They won Game 2 behind seven strong innings by Mike Moore. If the Giants were going to make this a series, not just a local party, they had to win Game 3 at home.

Candlestick was rocking for the Giants' first home World Series Game in 27 years. People around the Bay Area had left work early so they could be home in time to watch.

The earthquake struck at 5:04 p.m. PST, a time of day that would be etched in the minds of a Bay Area generation. Giants pitcher Mike Krukow was standing on the field, and he instinctively went into an athletic position, bent at the knees, to keep his balance. He looked up and saw the backstop swaying back and forth.

Krukow had felt "pretty good shakes" before. In 1987, the Giants felt a quake in their Los Angeles hotel early in the morning; two Giants were so scared that they went straight to Dodger Stadium at breakfast time and stayed there all day, even though the game was at night.

This felt different, Krukow thought. It was louder, and it lasted longer. Beyond the outfield, light towers rocked.

Finally, it stopped ... and the crowd erupted in cheers. How perfect was this? An earthquake in the middle of the Bay Bridge series! What could be more fitting?

Somebody made an impromptu sign: "Hey, if you think that was something, wait till the Giants come to bat." The Giants immediately started making jokes. Do you think this is what Craig meant by shaking up the lineup? Nobody realized just how big it was: 6.9 on the Richter Scale, one of the biggest earthquakes in California history.

Krukow did not sense anything was particularly wrong until he got back to the dugout. "One of the police officers, he was rattled," Krukow said. "He was the only guy that was rattled."

The cop explained that they had a brand-new communication system that was supposed to be infallible. It couldn't be knocked out.

"So?" Krukow asked.

"It's knocked out."

*****

When mass tragedy strikes, people usually say it is a communal experience -- that no matter your station in life, you feel the same way. And that surely happens ... eventually. But the initial reaction is individual.

Giants centerfielder Brett Butler, a born-again Christian, felt the earth shake and thought it was the Second Coming. "Is this it, Lord?" he wondered. Canseco said when he started wobbling on his feet, he thought he was having a migraine.

In Richard Ben Cramer's book, Joe DiMaggio: A Hero's Life, Cramer describes the 74-year-old DiMaggio, a San Francisco native, hustling off the field, to a limo in the players' parking lot, so he could get to his home in the Marina district. DiMaggio, Cramer wrote, told TV reporters he was looking for his sister, Marie. (She would soon call to say she was fine). The Yankee Clipper then walked away from his house with a garbage bag containing $6,000 in cash.

A's reliever Dennis Eckersley was in front of a mirror, combing his hair. (As teammate Dave Parker explained recently: "He's a pretty boy.") Eckersley had looked forward to this series more than any other Athletic; he saw a Series victory as his personal redemption after giving up Kirk Gibson's famous homer the year before.

The A's clubhouse went dark. Some players, like Eckersley and Parker, turned left as they left the clubhouse and ended up, in full uniform, in the parking lot. Stewart and others turned right and ended up on the field. Eventually, almost all the players ended up on the field, where they searched for their families.

Most of them had gone from thinking this was awful to believing everything was OK. Then the news trickled in, each update worse than the last: Power is out ... phones aren't working ... the Bay Bridge collapsed. Parker's wife, Kellye, had driven over the bridge less than an hour earlier.

The game was postponed. With many of the phone lines out, players and coaches could not reach babysitters to make sure their kids were OK. Canseco was spotted at a gas station, sitting in his car in full uniform to avoid autograph-seekers while his wife, Esther, filled the tank.

Krukow was living in a Marriott (his rental lease had expired at the end of September), and when he got back to his suite, "it looked like somebody had ransacked rooms. The television had bounced across room." They had no electricity, and slept with the windows open -- not because they wanted cool air, but because the windows would not close.

There were reports that hundreds had died.

Brett Butler had told reporters that "this World Series, you can take it or leave it." Giants outfielder Pat Sheridan said "we just want to get this over with, and get home to our families and the offseason." Third baseman Matt Williams said "right now, the World Series is pretty unimportant to us."

Around the country, and especially in the Bay Area, people wondered: should the World Series be canceled? It did not seem to matter that the 49ers simply moved a home game against the Patriots from Candlestick to nearby Palo Alto, or that Cal and Stanford played at home while the World Series was on hold. Those were just games.

The World Series was different. It was an event, inextricably tied to the earthquake in the public's consciousness. And since the Series had already been established as a Bay Area celebration before the earthquake ... well, how could San Francisco and Oakland party now?

The Series was pushed back to the following Tuesday, Oct. 24, and then finally to Friday the 27th. Commissioner Fay Vincent made the announcement at the Westin St. Francis in Union Square, with San Francisco mayor Art Agnos by his side.

"Churchill did not close the cinemas in London during the blitz," Vincent said. "It's important for life to carry on."

Besides, the World Series had already done a service for the Bay Area -- inadvertently. When the quake hit, many people were home to watch the game instead of on the roads at rush hour; after those initial reports that hundreds had died, the final number would be around 67. Baseball had saved many lives.

*****

There had never been an American sporting event like it: a party for one area of the country, interrupted by one of the biggest tragedies in that area's history. Once Vincent decided to restart the Series, the question for the players was: How?

The question was partly physical: a week and a half off between games is no way to stay fresh. The year before, the A's had a five-day layoff between the ALCS and the World Series, and some of the players thought it hurt them against the Dodgers.

This time meticulous A's manager Tony LaRussa was taking no chances. A few days before the series resumed, LaRussa took his players to their preseason home in Arizona to sharpen their skills and clear their minds. The A's held spring training in the middle of the World Series.

And then there was the mental part of the question. Days after saying the Series did not matter, would the players be ready? What if there were aftershocks during the game? Some expressed fears that pieces of Candlestick would fall from the sky.

And what would happen to Smoke? That was Dave Stewart's nickname; he was known as much for his cold stare on the mound as for any of his pitches. Now here he was, back at the scene of the terror, pitching Game 3 for the A's. Officially, Stewart was working on 11 days rest. But his mind had not rested at all. Could he lock in on opposing hitters the same way he always had?

A spot at the top of the park -- Section 53, Seat 24 -- turned into an impromptu shrine. That was where The Stick had cracked but not collapsed.

There was a moment of silence at 5:04 p.m., precisely 10 days after the quake struck. Then the crowd sang "San Francisco," the title song from the 1936 movie about the 1906 San Francisco earthquake:

It only takes a tiny corner ofThis great big world to make the place we love;My home upon the hill, I find I love you still,I've been away, but now I'm back to tell you ...San Francisco, open your Golden Gate ...

*****

Rescue workers threw out ceremonial first pitches. Then the teams picked up right where they'd left off. Stewart had a 2-0 lead before he threw a pitch and never looked back. There was a brief scare in the bottom of the ninth, with the Giants staging a hopeless rally: a bank of lights in right-centerfield went out.

It was a simple electrical problem. Fans were used to those by now. They pulled out cigarette lighters.

The A's won Game 3, 13-7 to take a 3-0 Series lead. In Game 4, Oakland took an 8-0 lead and won 9-6 to finish the sweep. The Giants never had a lead in any game. The Bay Bridge Series ended, mercifully, with Eckersley getting a three-up, three-down save in Game 4, a year after giving up that home run to Gibson. It was closure for the closer -- and for the region, too.

The A's celebrated like they'd just won the annual softball tournament at the Betty Ford Clinic. There was no champagne celebration, no shotgunning of beer. "It would have been the improper thing to do," Stewart said.

In the ensuing months and years, the Bay Area coped in typical American ways, for better and worse: solemn memorials; questions about whether the government was doing enough; reconstruction of buildings, including most of downtown Santa Cruz, which was virtually obliterated by the quake; and bickering over whether the Giants would -- or should -- get public money for a new ballpark.

People moved on -- in Brenda Stewart's case, literally. She left her house for a place in Oakland Hills shortly after the earthquake, and never moved back. She now lives in the Sacramento area.

"I always say, like when 9/11 happened: for people who live in those areas, the memory stays the longest," she said recently. "The rest of the world forgets."

She will never forget. But she didn't need that daily reminder, either.

Dave Stewart lives in San Diego, where he is a baseball agent. He said he doesn't think about that earthquake too often. But once in a while, he'll go back to his hometown, and he'll drive over the Bay Bridge, and he'll think back to 1989, back to the Bay Bridge Series, back to that moment when he was on top of the world and the world cracked.

Michael Rosenberg is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated, covering any and all sports. He writes columns, profiles and investigative stories and has covered almost every major sporting event. He joined SI in 2012 after working at the Detroit Free Press for 13 years, eight of them as a columnist. Rosenberg is the author of "War As They Knew It: Woody Hayes, Bo Schembechler and America in a Time of Unrest." Several of his stories also have been published in collections of the year's best sportswriting. He is married with three children.

Follow rosenberg_mike