Best untold Lakers-Celts memories

As you've been reading (perhaps ad nauseum) here and other places, there was nothing like Lakers-Celtics. It goes without saying that their rivalry made it special, but the personalities of the players, coaches, execs and even fans made them newsworthy on their own.

As the Finals scene switches to Boston for the next three games, my mind switches to my top 10 moments of covering these teams -- together and apart -- from two different eras, but mostly from that one long ago.

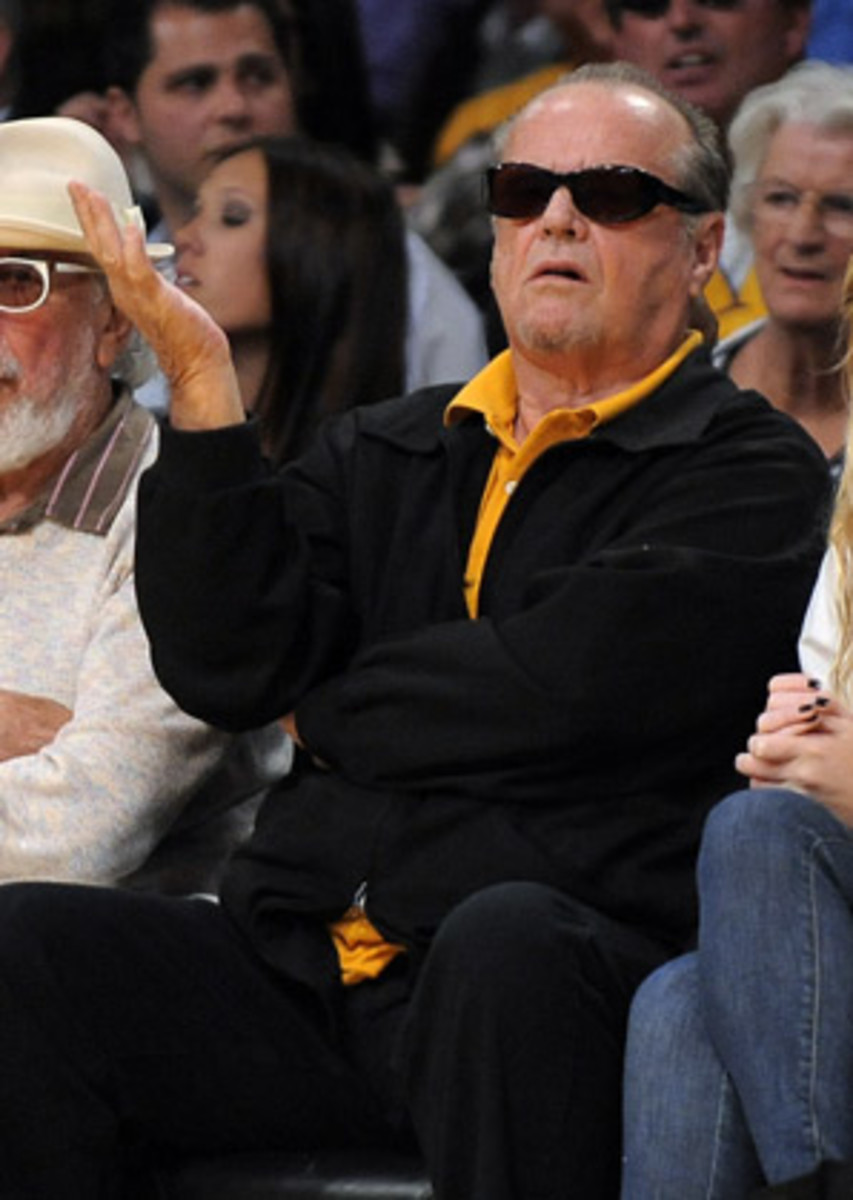

Between games of the 1987 Finals, Lakers superfan Jack Nicholson was taking a morning tour of Boston Garden. A bunch of reporters spotted him and we set out to get a few off-day quotes from the Coolest Man Alive. But Nicholson's face took on a look of horror as he spotted the encroaching hordes, and he retreated. It was an object lesson, one of I've learned several times since: While the worst player on the worst team in any sport is accustomed to off-the-cuff questioning, most Hollywood types depend on their publicity people to set up structured, agenda-driven ("I really feel I've done the best work of my career in this new movie ...") interviews in a controlled environment. I still love Nicholson and his constancy to his beloved Lakers, but, on that day, he was a little less cool.

On a regular-season trip I took to L.A. with the Celtics during the 1990-91 season, the actor, fresh off the success of Dances With Wolves, was working the Celtics' locker room after Boston's surprising 98-85 victory over the Lakers.

"Saw Dances, man," McHale told him. McHale was trying to be friendly since Costner, the brightest star in Hollywood at that time, hadn't gotten too far in a conversation with Larry Bird.

Costner seemed generally flattered, and, later, on the team bus, Celtics broadcaster Glenn Ordway asked McHale about his praise of the movie.

"Oh, that," McHale said. "Tell you the truth, I didn't see it."

(A wise decision, by the way.)

Lakers forward James Worthy was always considered soft by the Celtics, much as Pau Gasol is now. They respected Worthy's talents, but not his heart. I never bought it. I thought Worthy was a truly great player who, yes, depended mostly on finesse, but not at the expense of guts.

But he made his bones in the third quarter of Game 6 of the '87 Finals when he got his hand on a lazy pass from Kevin (McHale, not Costner) to Dennis Johnson, dived headlong along the floor to keep it from going out of bounds, and tapped it to Magic Johnson for a layup. That play started a Lakers comeback that produced a 106-93 win and the fourth of five titles in the '80s.

I was in Los Angeles for Game 1 of the above-mentioned series when that week's Sports Illustrated hit the streets. The cover photo was a memorable one of Bird with clenched fist over the tagline: CELTIC PRIDE. A reporter friend of mind said he was going to get Bird to autograph it. "That's a little weird," I thought, but I followed him into the locker room to see what would happen. Bird, never exactly an emotional open book to the media, grabbed it and went, "All right!" It was a great moment, even though he was reacting to the photograph ... not the story.

Two days before I was to fly to Los Angeles to do a story on the fading KareemAbdul-Jabbar in 1989, I sprained my left ankle playing hoops and was fitted with one of those Donjoy walking braces. I felt like an idiot since a) the story was about Kareem perhaps having hung around one year too long, and b) I always found the imperious Abdul-Jabbar an intimidating interview anyway. It was a total surprise when Abdul-Jabbar agreed to talk at his too-cool-for-words home in Bel Air. Being a Muslim, he removed his shoes before entering and I took off my right one. Kareem hesitated for a moment and looked down at my brace.

"I, uh, could take it off Kareem," I said. "It's removable."

"I'd appreciate it," he said.

So I did. Kareem did not suffer fools -- even limping fools -- gladly.

Midway through the 1985-86 season, SI assigned then-senior writer BruceNewman and I to follow the Lakers and Celtics prior to their midseason duel at Boston Garden. I drew the Celtics, which basically meant hanging around McHale and mining him for every possible nugget. He never disappointed. A few days before the game, I met him in downtown Boston where he showed up for an appearance in a half-beat-up Oldsmobile rental and proceeded to rag on the Lakers. "There's no one around here who doesn't think we're better than the Lakers," he said. "Last year? Hey, we took them to six games with Larry having one arm. [Bird had injured his right elbow in the Finals, which the Lakers won in six.] How can anyone in America like the Lakers? They don't drive Delta 88s."

His confidence defined the Celtics of that season, which ended with Boston's winning a championship.

This one is obvious because you've seen 100 replays of it. Game 4 of the '87 Finals in the balance at Boston Garden. Lakers trail 106-105. Magic has it near the sideline. He fakes a 20-footer and takes it toward the middle. My press seat was on that baseline, and I can still see the play unfold in my mind's eye. McHale and Robert Parish pick up the Lakers' point guard as he goes into the lane, and even Bird takes a step toward him before retreating to his own man, guarding against a Johnson dish. Johnson releases his hook shot, smooth as silk, and in it goes to give the Lakers a 107-106 victory and a 3-1 lead that becomes a championship in Game 6. I can still hear Magic gleefully riffing on the Abdul-Jabbar specialty and describing the shot: "It was the junior, junior skyhook."

Had the Celtics and Phoenix Suns not gone to three overtimes in an incredible Game 5 in 1976, I would call Game 4 of the '84 Finals the best championship series game ever. But it was the best I ever saw, ending in a 129-125 Boston victory in L.A. that paved the way for the Celtics' eventual seven-game victory. What everyone remembers was McHale's clothesline of Lakers forward KurtRambis, but what I remember was the person who helped Rambis off the floor -- one L. Bird. He must've thought, "Whoa, that was a little much even for this rivalry." Then again, by that time Bird had already mixed it up with Abdul-Jabbar.

As soon as the Celtics had routed the Lakers to win the title in '08, I thought of my story idea: Boston GM Danny Ainge. He had been the subject of the first story I wrote as an SI staffer, way back in 1981, when he was trying to latch on as a third baseman for the Toronto Blue Jays.

"Any chance you'll be in the office tomorrow morning?" I asked Ainge on the TD Garden floor after the game, as the delirium went on all around us.

"Come by at 11," he said.

He was already there, waiting, when I showed up, and we reminisced for two hours, his mind a steel trap for facts from two decades earlier. A follow-up story was never easier or more enjoyable.

The relationship of these two superstars has been laid out completely in recent months, in Jackie MacMullan's book, When the Game Was Ours, and an HBO documentary on their on-court rivalry. But their deep friendship was never that apparent when I was covering them in the 1980s, the height of their rivalry. They respected the heck out of each other, but it wasn't like they wasted much time tossing mutual accolades -- accolade-tossing not exactly a Bird specialty anyway.

But I remember interviewing Magic in Barcelona during the 1992 Olympics and asking him what he remembered most about the aftermath of his announcement that he had the AIDS virus, which had occurred about nine months earlier.

"I remember how much it affected Larry," he said, tearing up just a little.