Auburn's Malzahn in spotlight now, but roots go back to fading town

"This," Gus Malzahn told the Hughes Blue Devils, "is the big time, guys."

For those wide-eyed kids from a tiny farming community in the Mississippi River Delta, there was nothing bigger. For their 29-year-old, third-year head coach, too.

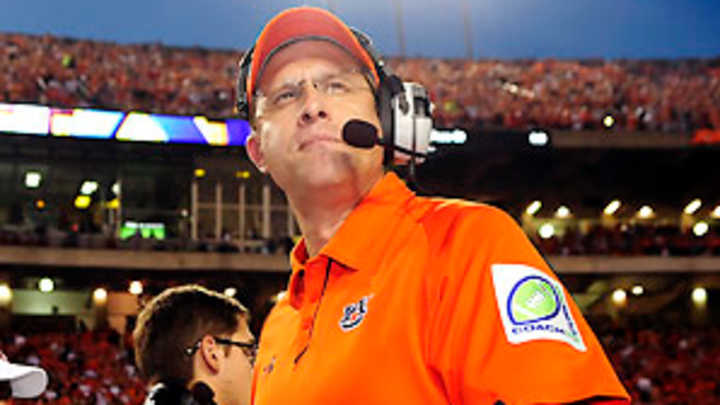

For many, maybe even most, Malzahn's story began this season, when he called the plays that Cam Newton executed so well (now that's coaching, Malzahn says), pushing Auburn to a perfect record and the BCS National Championship Game, propelling the Tigers' offensive coordinator onto every athletic director's short list of head-coaching candidates. The guy got a Gatorade bath from his players in the waning moments of the SEC Championship Game, and when was the last time you saw that happen?

Serious fans understand Malzahn came to Auburn from Tulsa, where his offenses were prolific, and that he broke into college coaching at Arkansas, where it didn't work out so well. Recruiting junkies know he was at Springdale (Ark.) High before that, with a talented bunch of players running an almost unstoppable attack. Spread offense devotees might remember him from Shiloh Christian in the same town, where passing and scoring records fell and a private school powerhouse was built.

But the roots go deeper. They go back to a small school in a fading town. Back to when a bus trip to Little Rock was an indescribably big event.

"It was a little overwhelming," Malzahn says, recalling the scene that night 16 years ago at War Memorial Stadium as a "three-ring circus" -- barely controlled. For the kids, sure. But also for the coach, a bundle of nerves who figured it was his one shot, and he'd better not blow it.

Bypassed by the Interstate, and by progress, Hughes, Ark., is six miles from the Mississippi River, but much further from the beaten path. The hamlet of less than 2,000 people is only 15 miles from I-40, but the high school principal once described it to me as "15 years ago." The school was known for its basketball; there wasn't much football tradition. It was the perfect Petri dish for a coach who was as hungry to learn as he was to win. Or just hungry, period.

Malzahn recently made news because, after turning down an offer to become Vanderbilt's head coach, he accepted a new contract at Auburn that will pay him $1.3 million a year. When I met him in 1994, he made less than $25,000 (at his current rate, a week's pay). Along with a young family, he lived in a trailer. He taught world geography to seventh graders, health to the high school kids -- and football to himself.

"I didn't have a clue what I was doing," Malzahn says, and when you laugh, he insists: "No, I'm serious, I really didn't."

A few years later, Malzahn would write a textbook on his trademark offense -- The Hurry-Up No-Huddle: An Offensive Philosophy -- that became a must-read for high school coaches. But when he was promoted from defensive coordinator to head coach after only one year at Hughes, he bought The Delaware Wing-T: An Order of Football, and then "went by it word-for-word." ("He bought a book?" wondered Rob Coleman, one of Malzahn's assistants at Hughes. "I didn't even know he could read.")

But let's stop there. All kidding aside, Malzahn was young, and he was inexperienced -- but he was also smart and confident. "He was definitely on his way somewhere else," says Michael Troup, who played quarterback for Malzahn at Hughes. Which is why, after Malzahn had been at the school for only one year as the Blue Devils' defensive coordinator, athletic director Charlie Patrick promoted him to head coach.

Malzahn's version of the story: "No one else applied." But Patrick counters: "I didn't advertise the position," and insists Malzahn was the only guy he wanted.

The position allowed Malzahn the freedom to try just about anything he wanted. What we see from Auburn today? Look close, and recognize that it all started then, when Malzahn meshed the I-formation with the principles of Wing-T misdirection he gleaned from that book, and then began experimenting. "He was always doodling," Patrick says. "He was never ever afraid to take a chance."

Malzahn didn't run the hurry-up offense in Hughes, or at least he didn't commit to it as a way of life. But he toyed with the idea after watching the seventh grade basketball team he coached push the pace and wear down opponents in the fourth quarter. The spread? Passing it all over the place? Hughes didn't have the personnel -- but boy, Malzahn wanted to.

The Tigers operate from the shotgun, but many of the schemes Auburn is running are nearly identical to the things Malzahn ran those early years at Hughes. And we do mean ran. Although his high school teams later became known for passing, his first teams ran. Power stuff. Sweeps. Option. But all of it was spiced with twists and turns that sometimes worked, sometimes didn't -- and sometimes still serve as the base plays Malzahn calls today.

"It blows people's minds to say we did the same stuff," Malzahn says, and he adds: "Football is a simple game."

Also, there were the gimmicks. If you've paid attention to Auburn in the last two seasons, you've seen them, often devastatingly effective. The Tigers practice them as part of the regular offense, the better to make them routine -- just like they did back in Hughes, when it seemed every week Malzahn had at least one new trick. They didn't always run them, but they did it often enough that John Manning, Hughes' principal at the time, remembers Malzahn as "a gambler." He once asked Malzahn: "Why do you run so many gimmick plays?" And Manning, a former football coach, wasn't asking because he liked them.

"Sometimes, you've got to trick 'em," Malzahn told him. And besides, he says: "It's fun."

Some of it didn't translate to the next level, of course. Like "Starburst," the kickoff return where five or six players huddled together, passed the ball around -- and then burst out running in different directions. Hughes scored several times on confused opponents. Malzahn's not sure where he got the play from, but he'd seen it somewhere, and you can see it on YouTube now, run by high school teams from all over.

There was also a fake field goal, "Where's the Tee?" The holder would get in his stance, then yell: "Hold on! Hold on! Where's the tee at? Where's the tee?" A wingback would shout: "I'll go get it!" He'd take off running toward the sideline, and if no defender followed him, they'd snap the ball and throw it to him.

Hughes ran a guard around, and tried all sorts of reverses and other wacky stuff, and it got to the point that whenever he introduced a new play, the Blue Devils would joke: "Coach, you've been playing too much Nintendo."

"We thought, 'Good night, that will never work,'" says David Brown, who played center. But often enough, it would. And says Brown, "It was pretty cool. It was kind of like you're just out there playing pickup football on Saturday afternoon, just drawing some plays up in the dirt. Wow, it was awesome."

The plays were drawn up, and then photocopied, on the game plans Malzahn handed out every Monday morning. Three, four, maybe five pages long, they were handwritten -- "It's how I think best," Malzahn says -- and they were very detailed.

Auburn players tell stories now about how at all times, text messages will pop into their phones. Malzahn will be watching film, and will glean some tiny bit of information -- say, a nuance in a receiver's route -- and he'll send it to them, right away. They're convinced the coach eats, sleeps and breathes football. Well, check that. Based on when those texts arrive, they're not sure he sleeps at all, just eats and breathes.

In Hughes, back before text messages -- heck, before e-mail and the Internet had become a way of life -- the players understood their coach was putting in long hours. Saturdays and Sundays, the three football coaches would gather to watch film at one of their homes -- there wasn't a TV available at the school -- and devise the game plan. It's all pretty standard stuff. But at Hughes, which played in the state's second-smallest high school classification? In the early 1990s? It was revolutionary. And already, Malzahn's ability to tune everything out and intensely focus on football was beginning to emerge.

"He could stay focused for months," says Coleman, the assistant and a close friend.

Malzahn's former players also remember a no-nonsense coach who could motivate, and seemed to genuinely care. Michael Bradley, a farmer now who played fullback then, likens his former coach to the fictional Eric Taylor ("he's the spittin' image," Bradley says), never mind that Hughes does not much resemble Dillon, Texas, or anything from the TV series Friday Night Lights.

But coaching at Hughes was about more than X's and O's. Many of the students lived in poverty. Malzahn spent much of his time cajoling players to join the team, pushing them to keep their grades up, and providing them with rides to and from practice and everywhere else in a 1988 Toyota Corolla hatchback. About that car: At the time, it was the family's only vehicle. A couple hundred thousand miles later, Malzahn lent it to a former player, who took it off to college. When it was returned in need of a transmission, so Malzahn's wife, Kristi, traded it for a fax machine. "And it wasn't a new fax machine," she says.

Soon enough, Malzahn left Hughes and moved across the state. He built an offensive philosophy, won state titles, earned a big reputation as a high school coach, got breaks he still doesn't understand -- "God's been so good to me," he says, "and I don't know why" -- and eventually found himself, somehow, nearing the pinnacle of college football.

"It's the opposite end of the spectrum," he says, from when he started. "But I'm a high school coach who just happens to be coaching college."

And he hasn't forgotten his first taste of the big time, in 1994, when a young coach took his team to the big city -- "uncharted territory," he called it -- for the championship game.

Just to get into the playoffs, the Blue Devils had to win their last two games by 13 and seven points because of a complicated tiebreaker. Once in, they played and won three road games, upsetting the two-time defending state champion in the semifinals. But among the most vivid memories is a stop for lunch, when Malzahn realized most of his kids had never been to a pizza parlor.

Hughes lost the title game, 17-13. In the final moments, the Blue Devils drove inside the 10. But a halfback pass misfired. A sure touchdown pass was dropped. Their last chance was intercepted. And the head coach still second-guesses himself. He knows he should have run the ball, because there was still time and that was the Blue Devils' strength. He remembers the awful empty feeling, that this was his one shot at the big-time.

"I thought I'd never be back," Malzahn says. "I thought I'd never get a chance again."

On Monday afternoon, Malzahn will enter University of Phoenix Stadium. He'll take a few moments to soak in the atmosphere. Yeah, uncharted territory again. But somehow, he figures, it will feel like he's been there before.