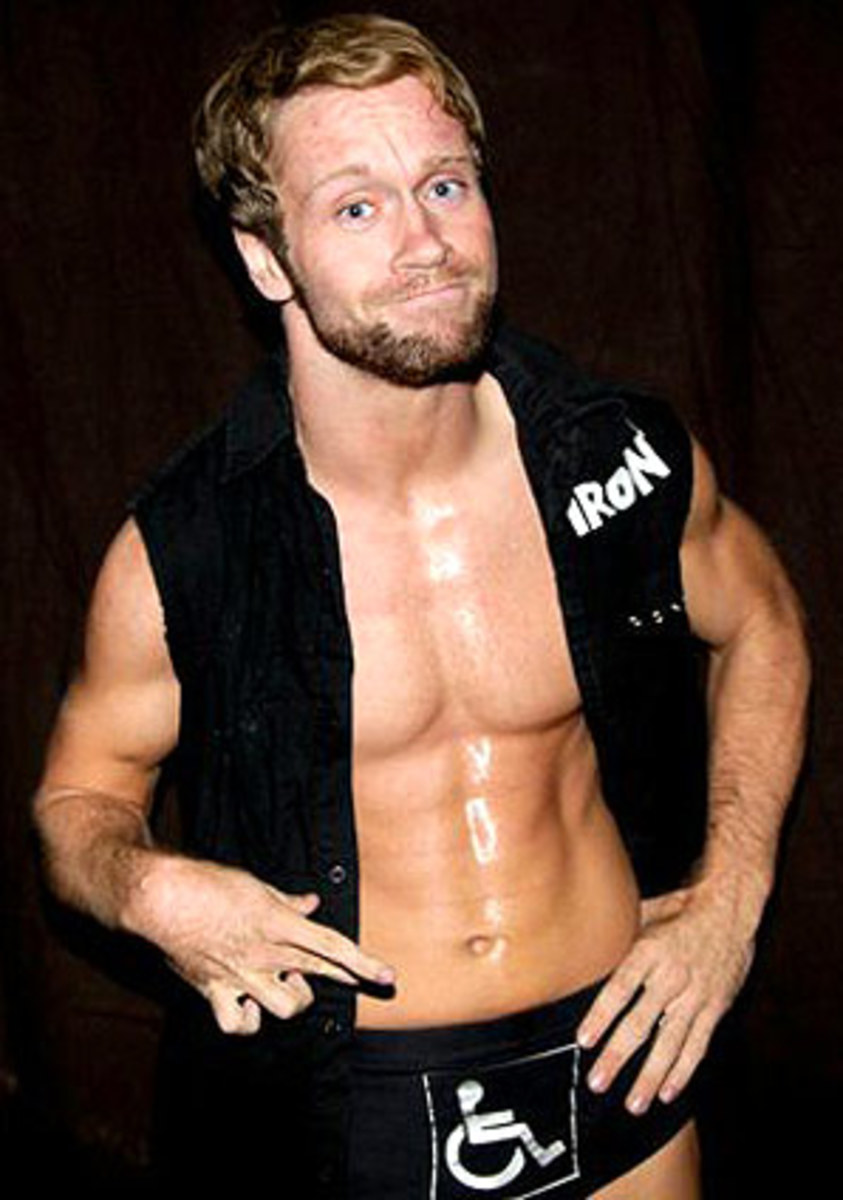

Gregory Iron, the Handicapped Hero, chases his wrestling dreams

A blond boy in a camouflage shirt, about 12 years old, sheepishly approaches the table and asks the so-called Handicapped Hero for an autograph. Iron obliges. "You got banged up pretty bad," the boy says.

The boy is right, but the chair shots are just some of the most recent blows. Surely the boy is not referring to the real-life basis for Iron's character -- the reason his right wrist is contracted, fingers clenched or bent at odd angles, forearm unable to turn over. If he tucks his right arm at his side or obscures it from view, you'd never guess that there's anything disabled about the upbeat kid whose pectoral muscles stretch his T-shirt -- no, Iron is not your average person with cerebral palsy. And few would guess how he's been otherwise banged up over the years: the poverty, his mom's addiction, the unplanned beatings he's taken in the ring.

But none of that is hurting him after the PWO taping. It's his damn left ankle, swollen from an awkward landing during a match in Wisconsin the weekend before. During the taping, the ankle acted up as soon as he planted to throw his first forearm. He couldn't run or jump and now he fears he might need to see a doctor. It's probably a sprain, he tells himself, and that's nothing compared to everything else he's endured. But the pain casts doubt on his next show for CHIKARA, an East Coast promotion, in New York City. And if Iron can't wrestle, what does he have?

*****

On the afternoon of the PWO taping, Iron is sitting on his bed in a second-story room in West Cleveland that he rents from PWO owner Wally Klasinski, the stepfather of his on-screen rival and best friend, Johnny Gargano. Cats roam the stairwell. Graffiti'd garages bookend the alley out back. On one of his walls is a pinboard filled with photos of him meeting grapplers Jake "The Snake" Roberts, the Sandman and others. Against another wall rests a bookcase lined with hundreds of wrestling VHS tapes and DVDs. On a third hangs a framed Hulk Hogan poster. The rest of the wall is bare.

"I don't live a life of luxury," Iron says, seated on a WWF Attitude blanket and WCW/nWo sheets. "I don't need much. Wrestling makes me happy."

Long before he was Gregory Iron, professional wrestler, he was Greg Smith, one-pound baby born one month prematurely. He was diagnosed with spastic cerebral palsy at 10 months after his father, Dwane, noticed he only picked up toys with his left hand. Greg spent his first eight years in weekly therapy sessions, happily rolling Play-Doh and tossing bouncy balls, never realizing he was doing exercises to strengthen his muscles, and unaware that his struggles with the right side of his body were uncommon. He drew pictures in his backyard clubhouse, played in the sandbox behind his house, thought himself just like anyone else -- until he started school. There, kids thumped their curled hands into their chests, calling him a retard or a cripple or gimpy. After that, Greg mostly kept to himself.

Home wasn't much more comforting. Dwane was a maintenance worker for the Cleveland school board and his wife, Gloria, worked as a printer while they raised Greg and his brother, Mike, a year his junior. By the time Greg was 8, the Smith family began unraveling. After her mother died, Gloria's longtime dalliances with drugs became a full-on habit. Items around the house began disappearing -- the microwave, the boys' Sega Genesis -- sold for a fix. Strange men turned up at the house, demanding money. Greg and Mike were too young to know that their broken TV antenna had been used to smoke crack, too naive to put things together when a man would spend the night while their father was gone and slip their mother cash when kissing her goodbye. The rent money Dwane left Gloria never made it to the landlord. After his cash also started vanishing, Dwane slept in jeans with his wallet in the front pocket.

When the couple separated, their sons chose to live with their mother; she convinced them that Dwane was a monster and won them over with candy. "She had us brainwashed," her oldest son says now, "but it turned out to be the worst decision possible." Gloria and the boys bounced up and down Cleveland's West 50th Street, boiling water for baths after the water was shut off, chased out whenever landlords realized their money wasn't coming. Greg and Mike spent long nights alone wondering where their mother was as they took care of their baby brother, Zach, hiding his formula in the closet so she couldn't sell that too. They spent a stint with an aunt and uncle 45 minutes away in Wellington, before Gloria went to jail in 1999 and Dwane won custody in the divorce. Finally the boys' lives began to steady.

Amid the whirlwind of taunts and evictions, wrestling was Greg's refuge. He had become a fan at his grandmother's house before he was old enough to read, watching the weekly TV shows and ordering pay-per-view supercards. He remained enthralled after her death, paying classmates with allowance money to tape shows he couldn't afford. He found sanctuary in his gargantuan idols, loving none of them more than Hogan -- Grandma's favorite too. At her funeral, an 8-year-old Greg slipped a Hogan action figure into her casket. As Iron remembers now, "He was that larger-than-life superhero that I wanted to be like someday."

*****

At the age of 19 -- just after WrestleMania 22, as Greg marks time -- he took his first steps into a makeshift ring in the basement of a brick box of a building called Turner's Hall, home of bingo games and Cleveland All-Pro Wrestling. After studying communications for a semester at Cuyahoga Community College, hoping to be a wrestling announcer, Greg missed spring registration because his car had broken down. That's when he scrapped the sideline plans and aimed for the ring. By then he'd packed 30 pounds onto what was once a 115-pound frame through creative weightlifting -- unevenly gripped bench presses, pull-downs with his back to the machine -- with a grip he couldn't break if he wanted to, forced by applying pressure to his palm to curl his fingers down. He called the number on a flier for CAPW and paid $50 to get what counts as a tryout in wrestling. ("I basically got beat up," he says.) He passed the test when he came back a second time for more.

His stage name plucked from his youth, when he'd call himself an "iron man" before anyone could call him worse, Iron took to learning the craft of hip-tosses and Irish whips and locking up an opponent with one dependable arm. Iron's trainer, a gruff man called J.T. Lightning, would challenge him before each new assignment, warning him that if he couldn't do this, he couldn't be a wrestler. Iron found a way to complete each one, adjusting as needed, turning to his left to bounce off the ropes with his good arm, jumping back up from every bump.

When his first opponent, an old-school tough guy named Michael Hellborn, asked him after his match if he hit him too hard, Iron snapped back, "Don't pity me." When Lightning took liberties with him in the ring, he took the bloodying and never asked why. When some guys slammed his head to the canvas so badly during a battle royal that he couldn't remember the match when he got backstage, he resisted going to the hospital. When he eventually gave in, he ended up staying in the ICU for three days with a bleeding brain -- the doctors said that if he'd gone to sleep, he might never have woken up. And when he ignored his doctor's advice and returned to the ring two months later, PWO turned his post-concussive fragility into a storyline.

Dwane comes to some shows; though predetermined outcomes be damned, he hates to see his kid lose. Mike makes it when he can. Zach, now 13, shows up to nearly all the local ones to root on his big brother; he wants to be a wrestler too someday. Gloria used to come from time to time, wincing when her son took a beating. She stopped coming a couple of years ago when she moved away. The last time Iron spoke to her was at the beginning of 2010 when he called to discuss Zach's missing Xbox. "In this life you only get one mama," she warned. "Maybe you'll appreciate me when I'm gone." She hung up.

Six months later, on July 4, 2010, Gloria overdosed on cocaine in a homeless shelter. She was 49. Iron was a pallbearer at the funeral. Afterward his aunts and uncles wanted to catch up with Gloria's oldest son, but Iron wanted to escape. He drove to a punk rock festival downtown, where wrestling matches served as sideshow to bands he'd never heard of. It was 95 degrees and humid when Iron wrestled Dave Crist outdoors before a small crowd that couldn't have cared less. After 10 minutes Crist pinned him and he went home.

*****

This summer had been rough for Iron. He'd lost his job at a local hardware store after clashing with a new manager who told him to choose between selling handsaws and his dreams. Others pitched in to help, Dwane taking him out for groceries, Klasinski no longer collecting rent. Mike, an assistant manager at a Chipotle, lent his brother $50 to help get him to an All-American Wrestling show he was working July 23 in Berwyn, Ill., a suburb 10 miles west of Chicago. It was there that WWE star CM Punk lent his hand to Iron's cause.

After Iron wrestled a tag-team match with Colt Cabana, one of the indie circuit's biggest names and Punk's real-life best friend, Cabana lauded Iron on the microphone, and then went backstage. When he returned to the ring he was accompanied by the man at the center of the wrestling universe, CM Punk himself. Punk quieted the crowd, which had begun chanting his name, then apologized for his language and turned to tell a weeping Iron, "You're f---in' awesome." Punk gave a speech of his own before he and Cabana lifted Iron in the air for a lap around the ring. There was the newborn in the incubator now pointing to a rowdy audience in appreciation, the kid they called a gimp hoisted on the shoulders of greats.

The moment was a YouTube hit, its multiple iterations totaling about 150,000 hits. New fans reached out to him on Facebook, Twitter and however else they could, telling Iron how much his story meant to them. Says Dwane, "The stuff that that guy said about him, it just broke my heart -- but it was a positive breaking my heart. I started tearing up. I was very proud of him."

More people now recognize Iron and approach him at shows -- he's more accessible at the gymnasiums, ballrooms and bingo halls where he works than performers in the 10,000-seat arenas of TV pro wrestling. Like thousands of other fledgling independent wrestlers, Iron hopes for a WWE contract and a chance to work the big-time shows he grew up watching. His supporters think he's a perfect fit, his cerebral palsy a ready-made storyline. "You wanna to see him get the crap kicked out of him," says fellow wrestler Rickey Page, "and then see him come back." It helps that the kid can work: Klasinski says he's as good as anybody on his roster. "If you look at a guy like Greg and don't see dollar signs and marketability, you're missing the point," says Joe Dombrowski, PWO's producer and play-by-play announcer.

In the parking lot after the AAW show, when Iron asked Cabana why he and Punk did all that, Cabana said "it was a gift," and now it was up to Iron to run with it. But there's only so much a wrestler can do. Iron has taken all the bookings he can get, wrestling whenever and wherever he can to gain exposure and get noticed. In 2010 he worked a pair of tryout camps in front of WWE officials in Kentucky, hoping to land a developmental deal. At the first he over-rehearsed his speaking and screwed up some drills, but at the second a trainer said he was the hardest-working guy there. The head of WWE talent relations even told him he could be a good fit if they brought back the cruiserweight division, or maybe as the underdog buddy of a guy like John Cena. Yet the cruiserweight revival remains a rumor. Cena's still a solo act.

"I know it doesn't happen overnight," Iron says, then shrugs. "But I want something to happen."

*****

"I don't know what I'm gonna do," Iron says. It's Sunday morning, some 12 hours after the PWO TV taping. His black 1999 Taurus is cruising on Interstate 280 in New Jersey, faded Hulk Hogan air freshener dangling from the rearview mirror. Two empty cans of Monster sit in the console cupholder, remnants of an overnight drive Iron's done most of himself, handing over the wheel to Boone for only 90 minutes. Iron's sore ankle spent much of the ride swaddled in a plastic bag filled with ice from the gas station where he paid $10 for a shower at 4 a.m., and now he's wondering whether he and his opponent can work around his ankle to put on a compelling match at the CHIKARA show in Manhattan that afternoon. And what if when he arrives he finds out he's supposed to win?

"It's a little bit dumb for you to come out here today," says Boone, himself no stranger to wrestling through pain, "but it's how you roll."

The wrestling life is cruel. All those falls take a toll on even consenting bodies, the long road trips doing no favors. The industry has taken its lumps in recent years thanks to steroid and human growth hormone scandals and a rash of premature deaths, many caused by the drugs some use to build muscle or for energy to perform night after night or to sleep at odd hours or to dull the pain. Like most of his wrestler friends, Iron shuns pills and doesn't drink or smoke. He pounds energy drinks. He ices whatever ails him.

Some guys get out while still relatively intact. The beat down at the PWO show was part of a storyline to write Hobo Joe, Iron's tag-team partner, out of the company. But even many who walk away end up coming back for more, never quite saying goodbye. Josh Prohibition, Iron's friend and mentor since Turner's Hall, now teaches high school government full-time and coaches baseball, but he got the OK from his principal and came back for a match against Iron this summer. Hellborn, Iron's first opponent, retired two years ago before his weakened knees got even worse, but he's working an upcoming charity show. Even the legendary Ric Flair, given an emotional send-off ceremony in 2008, is still flopping around at age 62.

Iron imagines his future differently. His underdog story comes with a shelf life. "It works now because I'm still a kid," he says. "I can't be 30, 33, 36 and doing this." Besides, he wants to walk normally when he's 50. He hopes to get signed to the WWE, wrestle a few years and then move to a role backstage. If he gains some fame, maybe he'll parlay that into motivational speaking. If none of that works out, well, he doesn't like to think about that. He's teaching himself video editing. He still has just that one semester of college credit. "There would always be an empty part of me," he says of leaving wrestling altogether. "I can't imagine it."

The CHIKARA match in Manhattan goes fine. Iron spends the preshow hours limping in circles around Highline Ballroom, testing his freshly wrapped ankle and nervously telling any willing listener about his injury. But he and Icarus, assigned by the promoter to concoct a win for the underdog, keep most of the match on the ground. It's only during a pair of top-rope leaps that Iron's ankle truly hurts, though he's still able to roll Icarus up for the pin after eight minutes. The match is enough to impress a well-known wrestler in the audience known as Homicide, who pulls Iron aside during intermission and tells him, "Everything Punk said was true."

Later that night Iron recounts the show while walking gingerly past blocks of Manhattan brownstones, flanked by Boone and Gargano, who wrestled on the show and will ride back with his friends to Cleveland. Iron describes the way the pain shoots from his ankle up to his toes, then mentions how another wrestler speculated Iron might have hurt his Achilles tendon. He distrusts such guesswork but fears even the suggestion. "That's, like, career-ending," he says. "I can't afford to have that."

Iron gets behind the wheel of his Taurus, stomach full after a 20-McNugget dinner and ready to put 450 more miles on a car that's racked up nearly 2,000 in the past week. By morning they'll be home, where Iron will continue to ice his ankle and begin walking in a brace. Soon he'll begin working at a Vitamin Shoppe, but that's just something to do between shows to pay the bills. After two weeks of rest he'll be back in the ring, ankle still sore, following Punk's advice to wrestle as much as he can, hoping to catch the right person's eye, waiting for a phone call that will change his life.