Holyfield, last great American heavyweight, says he's retiring

Evander Holyfield told SI.com he is retiring from boxing after a career that spanned nearly 30 years and a record four heavyweight title reigns. Holyfield will make a formal announcement Friday at a party celebrating his 50th birthday in Los Angeles.

"The game's been good to me and I hope I've been good to the game," an upbeat Holyfield said Monday from his Atlanta home. "I'm 50 years old (on Friday) and I've pretty much did everything that I wanted to do in boxing."

Many veteran observers will say the decision is long overdue. A little more than a decade ago, Holyfield was one of the most recognizable athletes on the planet, having generated more than a half-billion in pay-per-view receipts. Yet he won just eight of his last 18 fights. The New York State Athletic Commission banned him from boxing due to "diminishing skills" in 2005, forcing Holyfield's more recent bouts to such inglorious outposts as White Sulphur Springs, W.Va., and Corpus Christi, Texas.

He'd spent the past few years campaigning for a shot at Wladimir or Vitali Klitschko, the brothers who collectively rule the heavyweight division, with the goal of retiring as champion. But each Klitschko brother -- despite their mutual need for "name" opponents -- rebuffed Holyfield's persistent overtures out of respect. ("He is my idol," Vitali said in August. "I can't do it for any amount of money.")

Holyfield's dream of regaining the titles had been derided as quixotic. Yet when wasn't Holyfield dogged by naysayers? Fact is, if Holyfield paid mind to his critics, his career would have never gotten off the ground -- let alone reached the stratospheric heights he occupied throughout most of the 1990s.

There was never an off switch for the stubborn self-belief that propelled Holyfield, a blown-up light heavyweight who made overachievement his personal obsession. They said he couldn't pack enough bulk on his undersized frame to contend at heavyweight. (Oops.) They were positive he was too small to win a title in a division ruled by Tyson. (Wrong again.) They feared for his life when he finally met Iron Mike in 1996 as an 18-to-1 underdog. (You were saying?)

"Even at this old age I'm willing to fight the Klitschkos," he maintained Monday. "I can beat the Klitschkos, but they didn't want to do it. I can't make nobody fight."

And so it's over.

Holyfield walks away with a record of 44 wins, 10 losses, two draws and one no-contest, with victories over Tyson (twice), Riddick Bowe, George Foreman, Larry Holmes, Michael Moorer and Ray Mercer. Nicknamed "The Real Deal," the Georgia native held the lineal heavyweight championship in 1991-93 and 1994-95. He appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated six times, more than any other fighter besides Muhammad Ali (38), Tyson (15), Sugar Ray Leonard (12), Sonny Liston (10), Marvin Hagler (nine), Roberto Duran (eight), Foreman and Joe Frazier (seven apiece).

Still, Holyfield said his greatest memory remains being part of the U.S. Olympic team in 1984 that captured a record nine gold medals, with Holyfield settling for bronze due to a controversial disqualification.

"It made me feel that if you set goals you can reach them," Holyfield said of the Olympic experience. "It made me feel it was realistic to become heavyweight champion of the world. I had to go through more making the Olympic team [than becoming champion]. Once you turn pro and you have people on your team, they're going to get you [to the championship] whether you win or not, because they have something invested in you. When you're an amateur, you're on your own."

Holyfield won his first world title at cruiserweight in 1986 with the first of two memorable victories over Dwight Muhammad Qawi. Within two years, he'd consolidated the belts to reign as undisputed champion in a division of middling prestige, turning his sights on the heavyweight title held then by Tyson.

He was ringside in Tokyo when Tyson lost the title in stunning fashion to James "Buster" Douglas in 1990. He destroyed Douglas to capture the undisputed championship later that year, defending it three times before a unanimous-decision loss to Bowe that elevated both men's stature in the sport. The spine-tingling 10th round of that fight -- perhaps the greatest in the annals of heavyweight title bouts -- showcased everything that made Holyfield a pugilist of legendary vintage: the fearless in-fighting, the impossible punch resistance and recuperative powers, the indomiatable will.

Holyfield improbably regained the title from Bowe in 1993 -- the notorious "Fan Man" Fight -- and lost it on points to Moorer in '94. A heart defect forced a retirement. A faith healer's miracle cure prompted a comeback. And a knockout loss to Bowe in their rubber match -- capping perhaps the most memorable heavyweight trilogy this side of Ali-Frazier -- put Holyfield on skid row once again.

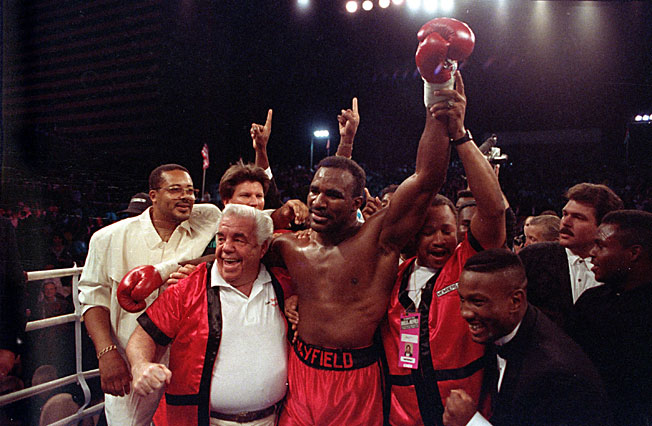

That's when he met a resurgent Tyson for the WBA heavyweight title in a 1996 fight where many ringsiders feared the worst. Only after his shocking victory, Holyfield recalled Monday, did he feel he finally got the appreciation he deserved.

"It gave me the credibility that I was always looking for in boxing," Holyfield said Monday of an upset that Ring Magazine named Fight of the Year. "When I beat Tyson, that's when everybody said, 'He is the real deal.'"

Holyfield twice retained the belt -- first when Tyson short-circuited in the highly anticipated rematch, next in a return bout with Moorer -- drawing then losing on points to Lewis in a pair of 1999 fights. He'd regain a recognized heavyweight title, if not the legitimate championship, for a record-breaking fourth time against John Ruiz in 2000.

While several U.S.-born fighters owned pieces of the fractured heavyweight championship in the years before the Klitschkos unified the belts -- among them Shannon Briggs, Hasim Rahman and Lamon Brewster -- Holyfield retires as the last active fighter to hold the undisputed heavyweight title.

While reports of boxing's demise have been exaggerated by the American sporting media, there's no question the heavyweight division has been outsourced abroad, badly undermining the sport's domestic profile. A weight class that's always served as a bellwether for casual-fan interest has since been ceded to larger-than-life giants from beyond American borders: Lewis (6-foot-5), Wladimir (6-6), Vitali (6-7).

Are smaller heavyweights like Holyfield and Tyson relics of a bygone era?

"It would take a person who has that confidence in their ability to be able to make the adjustments and be able to take whatever it takes to get their [punches] in," he said.

He believes the United States can one day reclaim its former glory atop the sport, but laments the effect the pay-per-view model has wrought.

"If they really want to put American boxing back where it belongs, they would put boxing back on free television," Holyfield said. "When boxing was good, everybody watched boxing on ABC television. It was Howard Cosell's baby and he kept it on the front lines. Now we don't support our amateurs no more. Now [viewers see boxers who] look like thugs who just came up one day from out of nowhere.

"We need to go back to the Wide World Of Sports days when people saw interviews with little kids who couldn't do nothing but fight because they didn't have the education or the opportunity. They worked hard and they were doing something positive. These people became champions and they're the reasons why American boxing prospered."

Despite whispers of a $10 million bankrupcy -- rumors compounded by the forthcoming auction of his prized possessions -- Holyfield insists the reports of his ruin are overblown. He's fathered 11 children with five women, marrying and divorcing (expensively) three times, but attributes "all these things that have happened to me" to financial naïveté. At last, Holyfield said, he's surrounded himself with people who have taken charge of his money situation.

"I've been exposed to ways to manage money now, people that have come to my rescue," he said. "There's a lot of fighters who just like myself never invested nothing in their life. Regardless of how much money you have, they never put me in a position to keep people from taking things from me. People started taking my stuff and I didn't know how to fight back.

"My money wasn't making money. When I could have had it in annuity all these years, I was afraid someone was going to take it. I lost a lot of my stuff because I didn't show up to court dates. I didn't know if you didn't show up, they just give your stuff to people."

Holyfield, who started boxing at 8 years old, said he'd like to remain around the sport but as a promoter rather than a trainer. He'd like to help younger fighters avoid some of the mistakes he made, to "make sure they get what they're supposed to get when they say they're going to get it." For now, he's enjoying time off after more than four decades of hard work and discipline. He spoke with equal parts enthusiasm and incredulity about a segment from Monday morning's episode of The View about a bus driver hitting an unruly passenger.

When asked if he was uneasy about Friday's official announcement, the official closure of more than 41 years in boxing, Holyfield simply laughed.

"Nothing to be nervous about," he said. "The hard work is done."