Hall of Famer Bill Sharman dies at 87

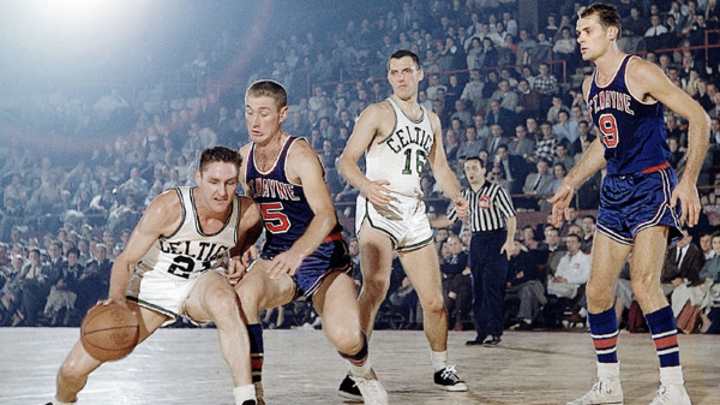

Bill Sharman (left) won four titles with the Celtics. (Hy Peskin/SI)

Hall of Fame player and coach Bill Sharman, who won five NBA championships, died Friday after suffering a stroke last week, according to the Los Angeles Times. He was 87.

Sharman's decorated career began when he was the Washington Capitols' second-round pick in the 1950 draft. After one season with Washington, he went on to play the duration of his 11-year career with the Celtics, winning four NBA championships and earning selection to eight All-Star teams and four All-NBA first teams. Sharman retired in 1961 with career averages of 17.8 points, 3.9 rebounds and three assists, and he earned induction into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame as a player in 1976. He was also honored as one of the 50 greatest players in NBA history in 1997.

After his retirement, Sharman coached the San Francisco Warriors and the Lakers in the NBA and the Utah/Los Angeles Stars in the ABA. He led the 1971-72 Lakers to 69 wins -- including a record 33 in a row -- and the NBA title in 1971-72, when he was named Coach of the Year.

"The most amazing thing about the streak has been our consistency," Sharman said in a 1972 Sports Illustrated article. "Only five or six of the games have even been close, and real luck only figured in one of them."

He finished with an NBA record of 333-240 (.581). He also won an ABA title in 1971. Sharman was inducted into the Hall of Fame as a coach in 2004.

“Be it on the court as a star player for the Boston Celtics, or on the sidelines as the guiding force behind the Lakers’ first NBA championship in Los Angeles, Bill Sharman led an extraordinary basketball life,” NBA commissioner David Stern said in a statement obtained by the Los Angeles Daily News. “More than that, however, Bill was a man of great character and integrity. His loss will be deeply felt. On behalf the NBA family, our thoughts and condolences go out to Bill’s family.”

Sharman served as a Lakers executive from 1976 to 1982. He selected Magic Johnson with the No. 1 pick in the 1979 NBA draft after winning a coin flip to earn the right to draft the future Hall of Fame point guard.

"I lost a coach, mentor and friend in the great Bill Sharman," Johnson wrote on Twitter Friday.

Lakers GM Mitch Kupchak also issued a statement.

"Bill Sharman was a great man, and I loved him dearly," Kupchak said. "From the time I signed with the team as a free agent in 1981 when Bill was general manager, he’s been a mentor, a work collaborator, and most importantly, a friend. He’s meant a great deal to the success of the Lakers and to me personally, and he will be missed terribly. My love and sympathy go to Joyce and Bill’s family."

As Herbert Warren Wind noted in a 1956 Sports Illustrated profile of Bob Cousy, Sharman was a rare two-sport professional athlete, spending time playing professional basketball for the Brooklyn Dodgers' minor league affiliates.

Cousy's running-mate, Bill Sharman, offers a very amusing case. During the winter, those who watch him tend to peg him in their minds as "Little Bill" Sharman. Comes spring, Sharmanswitches to baseball—last year he batted .292 with St. Paul in the American Association—and instantly undergoes a metamorphosis. For the next six months he is "Big Bill" Sharman, at 6 foot 2, one of the largest third basemen in organized ball.

Sharman led the NBA in free throw percentage seven times, topping out at 93.2 in 1959, and his career 88.3 mark ranks 12th among qualified shooters. Jeremiah Tax examined Sharman's charity stripe gift in a 1958 piece.

Preparatory stance shows body generally loose, with the knees slightly bent, right elbow pulled in above hip for firm control, right foot pointed at basket, left foot at 45 degree angle. Position is taken after deep breath and pause to relax from game tension. At this time ball is held with both hands and raised to level for sighting over top, ball obscuring most of net.

Waggling ball before shot loosens wrists, also gives "feel" of ball weight, which varies with player's condition. Shooting position, taken after waggle, has ball controlled only by tips of fingers, where sense of touch is concentrated. To prevent ball from rolling off side of hand, knuckles are at angle to seam, not parallel. Aim is at basket, not board.

At instant of release (left), ball should roll off only three fingers if held properly. (See bottom sketch on opposite page.) These are the thumb, index and middle fingers. Soft trajectory and back spin help ball "sit" on rim if it hits, rather than bounce off wildly. Follow-through is just as essential as in golf or baseball swing. If free-throw motion is smooth, follow-through flows naturally. Arm is fully extended and in straight line. Wrist is still at same angle as in first step. Eyes never leave basket. Sharman uses this type of free throw because it is the same in most essentials as the one-hand jump, so a player practices one while executing other.

As a coach, Sharman is credited with bringing the practice of a morning shootaround to the NBA. His style was laid out in a 1967 Sports Illustrated NBA preview.

Sharman worked his men hard on precise execution of set plays, the way he used to work himself as a Celtic, and he took the time to pick on individual faults, with the aid of an instant-playback TV set. At first this embarrassed some players and was resented, but in the long run it was appreciated and certainly has paid off. Another of Sharman's practices that inspired gripes was his insistence on calling morning workouts after a tough game or long plane ride the night before. He believes that, if left alone, many players will sleep all day before a game and will approach it in a lethargic state. One may sleep on his arm or in a cramped position or uncomfortably in a strange bed and not realize he isn't completely himself. The workout, Sharman feels, shakes out the deadness, and if his players do not agree, they are not complaining about it as much as they did.

When Sharman moved on to coach the world-beating Lakers, the topic came up again in greater detail in a 1971 piece by Peter Carry.

The fast break is Sharman's favorite mode of attack, but his deepest obsession is with pregame preparation. In addition to what he likes to call "the morning meeting" on game days, there are chalk-talks and calisthenics in the locker room immediately before games and strenuous two-hour practices on days when no game is scheduled. Sharman will rearrange travel plans, blow reveille at odd hours of the morning and even call a workout in an antiquated gym and unlit arena as he did in Philadelphia last week in order to give his players practice enough to suit him.

It is that morning meeting, however, that has proven so nettlesome to some players. This is particularly true for starters like Rick Barry, when he was with San Francisco, who figured if he was to play 40 minutes that night he should be resting during the day. Yet the game-day drills arc neither tiring nor very time consuming. In a 20-to 30-minute period Sharman's team does calisthenics—mostly loosening and stretching exercises—runs several leisurely laps, weaves through a few full-court layup drills and then shoots jumpers and free throws.

Sharman, who imposed the same regimen on himself when he was a player, insists that the drills stimulate his team rather than tiring it out before the game. "When guys doze off or mope around their room or the lobby, they get so logy they may not get sharp until after the game is lost," he says. "What I want them to do is develop a game-day routine. I want them to eat at the same time, shoot at the same time and take a nap for less than an hour and a half in the afternoon. If you sleep more than that, it will slow you down. The morning meeting also serves as a reminder, it gets the players thinking about the game. It also familiarizes them with the conditions they will be playing under, what the floor is like and how it feels to shoot into the background at the arena.

Frank Deford passed on this classic Sharman anecdote in 1967, concerning a full-court heave Sharman converted during the 1957 All-Star Game in Boston.

Sharman, standing at the opponent's free-throw line, hurled a long lead pass to Bob Cousy, streaking downcourt. It was a little long, and it swished through the nets 80 feet away. The arena was struck dumb at the sight. In the lull Sharman turned casually to Dick Garmaker, who was guarding him. "Don't play much defense, do you, Dick?" he said. They don't make three-point baskets like they used to in the old days.

Ben Golliver is a staff writer for SI.com and has covered the NBA for various outlets since 2007. The native Oregonian and Johns Hopkins University graduate currently resides in Los Angeles.