Two Months, Zero Losses

In the summer of 1971—the offseason before they would make history with the longest winning streak by a team in one of the four major men’s sports, a mark that remains unsurpassed 50 years later—the Lakers had a lot going on.

First there was the issue of who was in charge. Six weeks after losing to the Bucks 4–1 in the Western Conference finals, Los Angeles canned coach Joe Mullaney. “I am shocked,” said point guard Jerry West, who was, at the time, ranked fourth on the NBA’s all-time scoring list—and third among the Lakers. The two ahead of him, Wilt Chamberlain and Elgin Baylor, were nearing the end of their careers and struggling with injuries. The 37-year-old Baylor had played only two games in 1970–71, and Chamberlain, 35, had missed almost all of the previous season. West was 33 and had been largely healthy—until a knee injury sidelined him for the 1971 postseason. The three had played just 14 games together in Mullaney’s two seasons, yet he had taken L.A. on two strong playoff runs.

Still, the perception existed that Mullaney was too soft on the players. “[His] gentle, easygoing ways—and some odd personality quirks—made some of the players think he was just a nice, absent-minded old bumbler,” Chamberlain wrote in his 1973 autobiography, Wilt: Just Like Any Other 7-Foot Black Millionaire Who Lives Next Door.

Enter Bill Sharman. A Hall of Fame guard for the hated Celtics, he also had local roots, having been an All-American at USC. (He also had a tie to the local baseball team. He had been called up by the Dodgers when they were in Brooklyn at the end of the 1951 season as a reserve first baseman. But the Bums collapsed in epic fashion and Sharman never got off the bench, where he was sitting when Bobby Thomson of the Giants hit the Shot Heard Round the World.)

And Sharman’s coaching chops were undeniable. He had just led the Utah Stars to the ABA title and had taken the San Francisco Warriors to the 1967 NBA Finals. After Mullaney’s firing, Sharman quit the Stars, who promptly obtained a court order to keep him from taking another job. The legal wrangling went on for six weeks—Utah threatened to sue the Lakers for $5 million—before L.A. finally introduced him July 12.

At last the Lakers had their man, but was he the right man? In many ways Sharman was the opposite of Mullaney. His players in Utah described him as a “cold fish,” a “tyrant” and a “tactical psycho.” He was fond of having players do calisthenics in the locker room before games. (One struggles to imagine Tom Thibodeau telling his troops to take off the headphones and gather around for some jumping jacks.) Among Sharman’s innovations was the shootaround, a light practice the morning before a game—an NBA staple now, but revolutionary at the time. “When guys doze off or mope around their room or the lobby, they get so logy they may not get sharp until after the game is lost,” Sharman explained. “What I want them to do is develop a game-day routine.”

Chamberlain famously enjoyed the nightlife. On those rare occasions he was not entertaining into the wee hours, he often had trouble sleeping and was rarely out of bed before the time Sharman’s shootarounds ended.

Long before the first practice, writers had a field day ruminating on the compatibility of the two men, and even Schaus got in on it. “As [team doctor Robert Kerlan] was telling me,” GM Fred Schaus told The Los Angeles Times, “wait till Bill tells Wilt about his schedule for a 10 a.m. workout, 3 p.m. meeting and 8 p.m. tipoff. . . . You can hear Wilt right now saying, ‘I’ll be there, Coach. Name one. The workout, the meeting or the game.’ ”

Then there was Baylor. Sharman loved the fast break, but Baylor was in no shape for a track meet. In fact, there were issues with him within the organization even before Sharman arrived. In early June, Baylor, who had starred at Seattle, was offered the coaching job at Washington. “It might be a very good thing for Elgin,” Schaus said. “This could be an excellent opportunity.” It wasn’t exactly begging him to stick around.

From the outset, Chamberlain was stoic about the decision to change leadership. “It’s just like moving from one house to another,” he said. “It’s a lot of work—work that could be saved but isn’t.”

The Big Dipper knew all about moving houses—that was another thing he had going on in the summer of ’71. He uttered those words from a trailer on a lot in the Santa Monica mountains, where he was building an 8,300-square-foot mansion with a 360-degree view—and no right angles. “We borrowed an idea from Frank Lloyd Wright and made the house a series of interlocking equilateral triangles,” Chamberlain wrote. That included the sunken marble bathtub and a 14-foot front door.

Chamberlain and the Lakers got their first taste of Sharman in training camp. After a week at Loyola University it was off to Hawaii, an annual tradition that usually meant light practices and plenty of beach time. Sharman, though, put the team through morning practices in a stifling National Guard armory, then had them report for an afternoon meeting and an evening scrimmage. There was a lot of running by the players, and a lot of yelling about running by the coach, who developed a sore throat exhorting them to move faster. Said West, “I went over there with a suntan and came back without it.”

The regular season began with a four-game road trip in mid-October: three easy wins followed by a game in Atlanta that was close for three quarters. Just after halftime, West turned his ankle going for a rebound, an injury that sidelined him for two weeks. The Lakers went 2–3 without him, but while Baylor’s numbers (11.8 points in 26.6 minutes per game) were passable, it was clear that he didn’t fit into Sharman’s up-tempo system.

What happened next depends on whom you ask. Baylor wrote in his 2018 autobiography, Hang Time, that Sharman requested a meeting, which he avoided for a few days. When Baylor finally checked in, the coach told him that Jim McMillian, a second-year forward from Columbia, would be replacing him in the lineup. “I wanted to go for Sharman’s throat and flip his desk over,” Baylor wrote. Sharman then asked Baylor what he thought, and the Hall of Famer stood up and said, “I’m going to retire.”

According to Charley Rosen’s 2005 book, The Pivotal Season, which included interviews with Sharman before he died in ’13, Sharman and Schaus summoned Baylor after practice Nov. 2, two days after a loss to the Warriors. When they told him he’d lost his starting job, Baylor pleaded for more time to get into shape, but Sharman held firm.

What everyone agrees on is that on Nov. 4, Baylor announced his retirement. “Out of fairness to the Lakers and to myself, I’ve always wanted to perform on the court up to the level and up to the standards I have established during my career,” Baylor told the assembled press at the Forum. “I do not want to prolong my career to the time when I can’t maintain those standards.”

The next night West would return to the lineup to face the Baltimore Bullets—and the Lakers would embark upon an unprecedented run.

The amazing thing about the 33-game winning streak is how easy the Lakers made it look. The Bullets kept things close, but eventually Chamberlain’s defense and a 22-point, 13-rebound performance from McMillian proved decisive. The next night L.A. routed the Warriors in Oakland, then made it three wins in three days by beating the Knicks at the Fabulous Forum. (This was obviously before DNP-rest was a thing.)

Two road victories followed, including a 40-point blowout in Philadelphia. The Lakers made a quick trip home to beat Seattle, then reeled off another three wins in three days. The most telling was the last of those, when the Celtics visited the Forum. Ten years earlier Chamberlain had averaged 50.4 points on 39.5 shots. Against Boston he attempted two field goals and made one, a dunk off a loose ball in the third quarter. He did, however, have a rare points-less triple double—31 rebounds, 13 blocks and 10 assists—in the 128–115 win. “There were 14,” Wilt said of his blocks after the game. “I counted.”

The fact that the Dipper was shooting so infrequently was no surprise. “Over his 12-year career Chamberlain has been caught in more different poses than Twiggy,” Sports Illustrated’s Peter Carry wrote in December 1971. He had been a scorer, a passer, a low-post threat and a high-post facilitator. Sharman’s new marching orders: Play defense, rebound and start the break. “The outlet pass was something I had to be very conscious of earlier this season,” Chamberlain said in December. “It was a change of style for us then, but it has become second nature now.”

Wilt and his new coach got along fine after Sharman explained that he couldn’t allow Chamberlain to opt out of practices because it would set an unwanted precedent. It also helped matters that Chamberlain wasn’t just the star center—he was the team captain. Baylor had been the only captain the Lakers had ever had. When he retired, Sharman wanted West and Chamberlain to share the duty, but West said he wanted to focus on his play, leaving the Big Dipper wearing the C. He never did warm to shootarounds, but when Sharman offered the team a day off after the 40-point win over the 76ers, it was Wilt who decided the team should hit the floor.

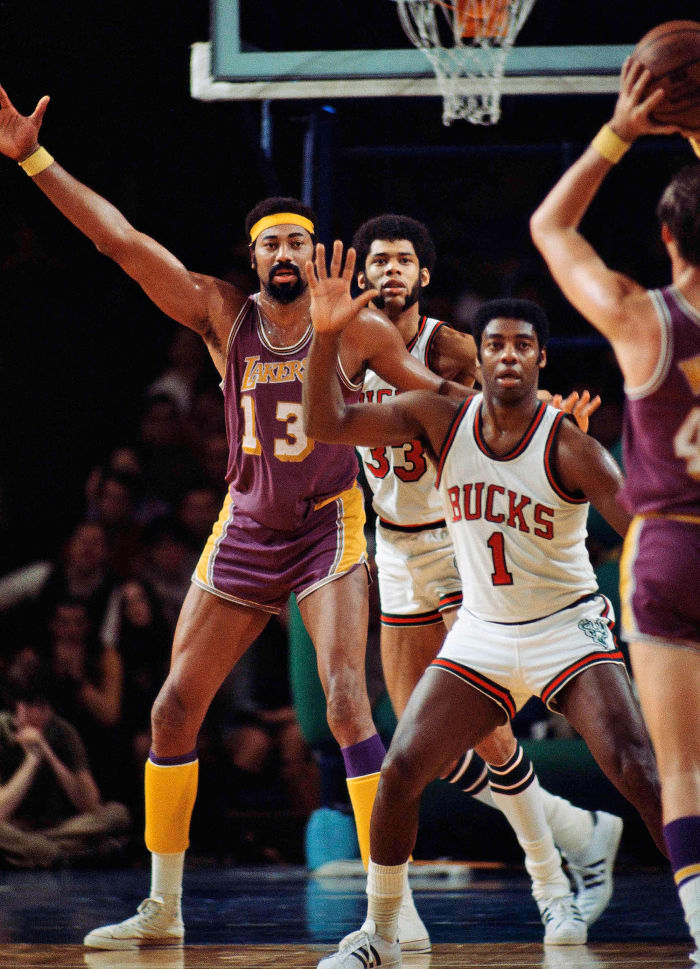

Victim No. 11 was the Bucks—who just happened to be the holders of the NBA’s longest run, 21 straight wins the previous season. They came to the Forum with a 16–3 record, but L.A.’s guards hounded center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar every time he put the ball on the floor, forcing 13 turnovers, and Chamberlain outrebounded him 27–16 in a 112–105 victory, L.A.’s eighth in 13 days. A sellout crowd of 17,505 saw it, as well as 3,197 fans who watched on closed circuit, since the game wasn’t on TV. (Fans in L.A. got Monster Zero, in which Godzilla and Rodan team up to battle an intruder from space.)

From there it was back to blowouts. By the second week of December the streak was 20, and L.A. needed only to beat the Suns at home to tie Milwaukee’s record. It wasn’t going to be easy, though. The Suns were riding an eight-game winning streak of their own, and the Lakers were playing their third game in three days, following road games in Houston and Oakland.

Still, a West jumper with 4:44 left put the Lakers up by 12. They would not score another basket in regulation. Phoenix stormed back to tie the game at 111, and Connie Hawkins had a shot rim out at the buzzer that would have ended the streak. Instead, Goodrich hit three huge jumpers in overtime as the Lakers pulled away 126–117.

Two days later, the Lakers returned to the Forum for their chance to set the mark against the Hawks, who entered the game in last place in the Central division. L.A. led just 96–95 with 1:01 left when Gail Goodrich, who had spent most of the fourth quarter on the bench for defensive purposes, found Chamberlain under the hoop for a dunk. Three steals in the last 39 seconds sewed up the ugly, 105–95 win. “We had been playing good basketball up to the latter part of the stretch,” said Chamberlain after the game, sipping on 7-Up as glasses of champagne sat untouched nearby. “But the pressure began to catch up with us. We all got a little tired. It’s been tough. . . . Really, I’m just very glad it’s over.”

But it wouldn’t be until they lost, which they hadn’t done since Halloween. With the NBA record, the focus, at least among the media, turned to the New York Giants, who won 26 major league games in a row in 1916, the longest streak in American professional team sports. That record fell in Baltimore three days before Christmas, when the Lakers beat the Bullets 127–120. “I don’t think any of the players were paying particular attention to it,” said West, who had 37 points and nine assists.

Los Angeles then closed out a perfect December, only the second time in NBA history a team hadn’t lost in a calendar month. (The first had been the Lakers’ November.) A 134–90 blowout of the Hawks on Jan. 7 made it 33 in a row and set up a dream showdown two days later: at Milwaukee.

The rematch had the intensity of a playoff game. With the Bucks up 36–34 midway through the second quarter Abdul-Jabbar picked up a loose-ball rebound and laid it in. Lakers forward Happy Hairston fouled him, mildly undercutting Abdul-Jabbar as he hung onto the rim. They were tangled as they landed, and Hairston put both of his hands down to balance himself—at which point Abdul-Jabbar decked him with an uppercut. This being 1972, the benches didn’t empty and most everyone seemed nonplussed. Keith Jackson, calling the game on ABC with Bill Russell, couldn’t even muster up a Whoa, Nellie!, stating plainly, “I actually think Jabbar hit him.” (After the game, Kareem said, “I simply lost my temper.”)

Hairston was called for a personal foul and Abdul-Jabbar merely received a one-shot “punching foul.” Hairston missed it.

The Lakers shot horribly all day (especially Goodrich, who was 5-of-20) and turned the ball over with stunning regularity (they finished with 24), but three straight buckets by reserve Flynn Robinson pulled L.A. within 94–90 in the fourth. Then Goodrich reentered, Robinson sat down and Abdul-Jabbar took over, sparking a 16–2 run that put the game out of the reach and the streak to an end. He finished with 39 points—23 in the second half—as Milwaukee won 120–104.

The game was, like much of the streak itself, strangely devoid of drama. In the 33 wins, L.A. was dominant, outscoring its opponents by an average of 123.3–107.3. They were taken to overtime just once. Four times they won games on three consecutive days—each time the second game was a road trip.

And they flew commercial.

In the locker room, Hairston showed off the bruise on the side of his face. “Sure, I fouled him,” Hariston said. “Fouls are part of basketball. Slugging isn’t.”

Sharman, who had been carrying a speech in his pocket to read when the streak ended for so long that it turned yellow, decided not to deliver it. Said the coach, “I was going to say corny things like, ‘Well, Jerry blew another one.’ ”

Probably for the best.

The Lakers dropped three of their next five, but that proved a minor irritant—they followed that with eight straight Ws. (Another annoyance: Sharman’s ongoing voice troubles now required him to carry a megaphone at practice.)

On March 10, L.A. routed the Cavaliers 132–98. The next afternoon Wilt threw a housewarming party at his mansion. According to Chamberlain, the team rarely socialized. “Surprisingly, there weren’t any close friendships on the Lakers,“ he wrote. Nonetheless, Chamberlain invited all of his teammates, even West, who had snubbed him a year earlier when the point guard threw his own party.

The 350 guests—including O.J. Simpson and all of the Lakers—were greeted by Chamberlain, who wore a gold leisure suit crafted from antelope skins and showed off amenities such as a bedspread made from the nose fur of 17,000 arctic wolves, an entire year’s bounty. Chamberlain had bought the fur years earlier and kept it in cold storage until the time was right to use it. Guests who wanted to enjoy the “purple room“ had to remove their shoes, as the floor was covered with wedge-shaped foam sectionals that surrounded a circular waterbed, all of it encased by mirrored walls. (Let’s face it—people going into the purple room were probably going to take their shoes off anyway.)

The party broke up 15 hours after it started, with a catered 4 a.m. breakfast. That night the Lakers beat the Buffalo Braves by 39. Wilt made all five of his shots and grabbed 17 rebounds.

Los Angeles went on to finish the regular season 69–13, a record for wins that stood until the Bulls won 70 games 24 years later. McMillian more than justified Sharman’s decision, averaging 18.8 points, third on the team, behind Goodrich (25.9) and West (25.8). The closest any team has come to the 33-game streak was the Heat’s 27-game jag in 2012–13.

In the playoffs, the Lakers swept the Bulls and beat the Bucks in six tough games before dispatching the Knicks in five in the Finals. “This is the greatest team I’ve ever been on,” said West, who knew he and his team were in a much better place than they had been 12 months earlier. “This will be one summer to enjoy.”

More NBA Coverage:

• NBA 75: SI's Favorite Moments of All Time

• Kevin Durant Is Doing It All For the Nets

• What's Wrong With the Celtics?