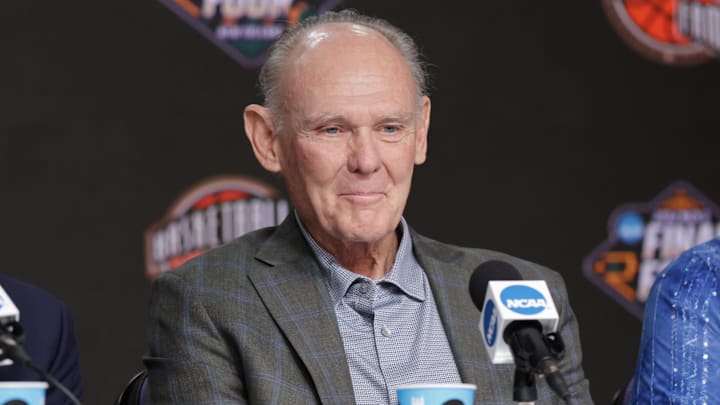

George Karl Explores How the ABA Was ‘a Godsend for Sports’

Before George Karl was an NBA head coach, before leading the Seattle SuperSonics to the NBA Finals, before stints as head coach in Milwaukee, Denver and Sacramento, before collecting 1,175 wins on the sideline, Karl was a heady, 6' 2" point guard with the then–American Basketball Association’s San Antonio Spurs, spinning the red, white and blue ABA basketball until the league merged with the NBA in 1976.

Karl has not coached since 2016, but he has not stopped working. These days he’s an executive producer of Soul Power, a four-part documentary on the rise and fall of the ABA that is streaming now on Prime Video. Karl joined me for a conversation about the ABA, its legacy and what a coach with decades of experience thinks of what today’s NBA has become.

(Conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.)

SI: You were drafted by the NBA and the ABA. Why did you decide to play in the ABA?

George Karl: I was drafted by the Knicks in the fourth round and I was drafted [in the sixth] by the Memphis Tams. The Knicks offered me a one-year guaranteed contract. Donald Dale was my agent at that time, and he was trying to get me multiple years, and he ran into Angelo Drossos of San Antonio and talked him into it. And I ended up with a three-year guaranteed contract with the Spurs, and I got in my Porsche and drove from Chapel Hill to San Antonio, Texas, one late September afternoon.

SI: It’s wild to think now that the ABA was born, in part, because back then the NBA was too boring.

GK: I thought the ABA was a godsend for sports, but especially for basketball and especially for the Black athlete. Because the ’60s and the early ’70s was a very troubled time in America. The Vietnam War, the Black and white civil rights movement was going on, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X and the Kennedys, and I really thought, in a crazy way, the entrepreneur mentality of the ABA scene, “We can do better than the NBA,” was a godsend to guys like me.

Because I don’t know if I make the NBA with only, I think, 12 teams or 13 teams. All of a sudden, there’s 25 teams, and because of that, a lot of guys got to play basketball in the NBA and the ABA, got paid to play. But more so than anything, I think it opened up the window for that segregated Black athlete that was now being slowly, very slowly, integrated into the white college system and white NBA.

And what we found, I think at that time, there was a little bit of a feeling that the white people won’t come out to watch the Blacks. But the truth of the matter is we love to come out and watch athletes and compete and play the game. And in 1970, the game of basketball was, what, third or fourth on the list of popular? And today, it’s the second most popular sport in the world. I know we want the NFL football to be king, but worldwide, soccer is king and the NBA is second.

SI: One of the athletes that the ABA gave an early opportunity to was Connie Hawkins, who was not welcomed in the NBA at that time. Do you think that basketball would’ve known about Connie Hawkins on the level it does without the ABA?

GK: No. Not only Connie Hawkins, Doug Moe was a part of that system, Roger Brown was a part of that problem. We had a lot of guys that would’ve never made pro basketball. They wouldn’t have been given the tryout, they wouldn’t have been given the opportunity. The ’70s was a time of civil rights and, in a lot of ways, I think the world of basketball was expressing the freedom that our country was searching for a little bit. Our freedom of rights, both Black and white, but also women were all searching at a hard, intense way in the ’60s and the ’70s when the ABA was founded.

SI: You played several seasons with the Iceman, George Gervin, down in San Antonio. What's your favorite George Gervin memory?

GK: I know no one wants to hear this, but I think George Gervin might be one of the top five greatest scorers of all time. I played with him every day, and the guy made the offensive end of the court look easy. Now, we have a guy today that makes it look easy in [Nikola] Jokić, but I never played and I never saw a guy for almost 25, 30 years make the game as easy as Iceman made it. Iceman would get 40, but he would shoot 17 for 22. He wasn’t a volume shooter, he was a very efficient scoring machine, 6' 9". If you were big, he took the outside. If you were little, he took the inside. Pretty simple.

SI: The ABA actually created the dunk contest. Did you think back then the dunk contest would become the phenomena it became?

GK: Well, I actually was talking with a couple people last night about the osmosis of the dunk. And I think the big key to the NBA is, at the end, when we merged with the NBA, we had David Thompson, people said he could touch the top of the backboard. And then we had Julius Erving. Nobody in the NBA had that much athleticism, and I think when you play faster, you get more dunks in the game, the dunk became the fan-popular event. We love seeing them, we love lobs, we love backdoors. We love anything that creates a dunk.

Julius won the first one in ’76, and I think for about 30 years, that was the biggest thing at the All-Star Game, the dunk contest. The last, I think, 10, 20 years, it’s fizzled, because no one wants to take chances. The guy that’s won the last three years [Mac McClung] is a little guy. I still think there are guys that can dunk the ball at an amazing skillset, but they might miss and they don’t want to do that anymore, so we don’t take that chance.

I think LeBron [James], I think he’d be a great dunker, but he doesn’t want to take a chance of not being successful with doing it. One of the greatest dunkers I ever saw in the Slam Dunk Contest is Larry Nance. I think he won, in my mind, the most dominated dunk contest of all time. But we’ve had some unusual winners in the dunk contest, but now the three-point shot is why we watch the All-Star Game. It’s had a crest and then it’s come back down to where it doesn’t have a lot of popularity right now.

SI: What do you think of the way the game is played today?

GK: I’m not pessimistic, but I think we take too many threes. I think the game has gotten soft a little bit. I think the league knows all this. I think they’re trying to make it more physical, but more athletes should be put on the court. The bigger they are, the faster they run, the quicker they are, I think you’re going to see the game get really, really good. I think right now we’ve plateaued a little bit.

A lot of those guys are young right now, and I think they’ve got to mature into champions, but I think they will. Last year, we got Oklahoma City. I think Detroit is a good young basketball team, playing very well. I think Denver’s going to try to get back into the fight. I think Kevin Durant in Houston’s going to be really good, so I think we have a lot of possibilities to get back into maybe a hot time, but I just love being a fan and enjoying watching it.

SI: Is there an NBA player you would have loved to coach?

GK: I always loved point guards, but I think one of the greatest things we’re seeing in today’s game is Nikola Jokić might be the best point guard in the NBA, and he plays center. And I think that’s a compliment to the evolution of the game, that our big guy now can touch the ball a majority of the time, and that’s never happened in our game until now. And the big guy’s not only going to be able to score underneath the basket and protect the basket, but now he’s got to make the three and make playmaking moves. Jokić would be one guy that I would just love to be in his presence and pick his brain on what he sees and what he thinks.

SI: The ABA was a phenomena. Why did you think it didn’t last longer than it did?

GK: Well, it all comes down to the money of it. Today’s game, it probably would’ve made it because of TV money. But back then, we were trying to be a community, trying to make people get engaged, involved. I remember, in the ABA, everybody said we were crazy for trying to take basketball to Atlanta, Georgia or down to Miami, Florida, or to New Orleans or to Dallas. As early as the ’60s and ’70s, people didn’t know if they would support those things. And the NBA, I think, told the world, told America that, “Yeah, if you will come, we’ll come watch it.”

My two wishes [are] that the NBA would take all the ABA stats and incorporate them into the NBA, like football has done and baseball has done. And the other thing, I’m hoping this happens, I’d like to see the red, white and blue ball come back. Why not? It’s a marketing league, why don’t we have a red, white and blue ball?

SI: What would you say is the legacy of the ABA?

GK: The first thing that comes to my mind is that Black and white basketball was always separate, from the 1920s all the way up until, really, the late ’60s. And I think the game of basketball, because of the merger, integrated the game of basketball faster than any other sport in America. And because of that, I think we had success. When other people were always worried about, “Hey, we can’t do this,” or, “We can’t do that,” the ABA said, “Screw it. We can do that. We can make it work.” And it worked, and it worked very well.

More NBA from Sports Illustrated

Listen to SI’s NBA podcast, Open Floor, below or on Apple and Spotify. Watch the show on SI’s YouTube channel.

Chris Mannix is a senior writer at Sports Illustrated covering the NBA and boxing beats. He joined the SI staff in 2003 following his graduation from Boston College. Mannix is the host of SI's "Open Floor" podcast and serves as a ringside analyst and reporter for DAZN Boxing. He is also a frequent contributor to NBC Sports Boston as an NBA analyst. A nominee for National Sportswriter of the Year in 2022, Mannix has won writing awards from the Boxing Writers Association of America and the Pro Basketball Writers Association, and is a longtime member of both organizations.

Follow sichrismannix