The Assassin and The Reverend: Remembering the late Jack Tatum

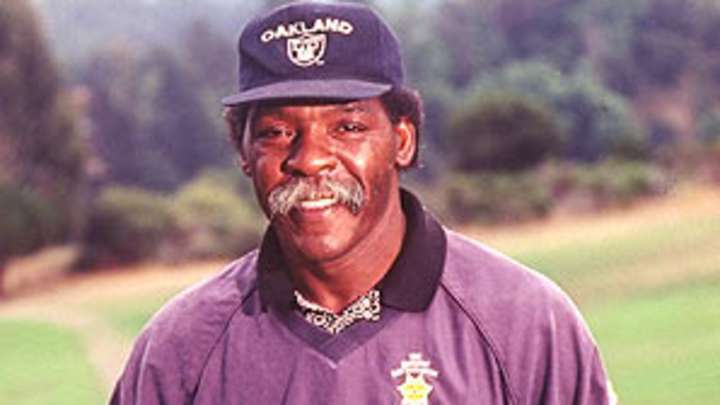

The face was weathered, etched by a lifetime of carrying a very heavy weight. The gait was slightly awkward; he'd lost his left leg below the knee in 2003, a casualty of diabetes. But on this night last winter, as fans clustered around him at Fred Biletnikoff's anti-drug foundation dinner in a hotel ballroom south of Oakland, Jack Tatum was not wearing the expression of an assassin. "You never make a tackle with a smile on your face," Woody Hayes had told him back at Ohio State, but on this night, his smile was wide, and open, and welcoming. The graying dreadlocks that swooped all the way down to his waist -- hair that spoke of a 61-year-old man who had always lived by no rules but his own -- swayed as he turned to accommodate each new autograph-seeker.

The hair had always been part of The Assassin's signature. In the 1970s, as the most storied and feared member of the Raiders' fabled defensive backfield -- "The Soul Patrol" -- Tatum had sported a fearsome Afro and a Fu Manchu and a menacing glare as he bore down on opposing receivers the way a tractor-trailer might bear down on a squirrel on a rural highway. A three-time Pro Bowler, he was the hardest-hitting safety the game has ever known. A Sports Illustrated poll named him one of the top five defensive backs of all time. NFL.com named him the sixth "most-feared tackler of all time."

Mike Siani, a Raiders receiver of the time, puts Tatum in the top two: "Pound for pound, he was the toughest football player I've ever seen. The only guy I could ever compare him to is [Dick] Butkus."

"When Jack hit someone, it was a different sound," linebacker Phil Villapiano told me. "There was a different sound between everyone else's hits and Jack Tatum's hits."

At Biletnikoff's party, I introduced myself to Tatum, and told him I was writing a book about his Super Bowl-winning Raiders of 1976: the last team of the old era, when you could be an outlaw and a rebel and a partier, and still play championship football. "Cool," he said. "Call me." I did, and left a few messages. But his health was failing. I didn't want to press. I knew that, 32 years after the Darryl Stingley play, the hit for which he'll forever be known, he was still reluctant to give interviews.

Then, one day, Tatum called me back, and we talked about the many unknown sides to the man. Of his grandfather's farm in North Carolina: "If I hadn't played football, I'd've probably been a farmer," he told me. "I just liked the peace and serenity." Of his other nickname on the Raiders -- The Reverend -- because, off the field, he was so contemplative and quiet. "Both my dad and grandfather were quiet and reflective guys, but they were real men," he said. Clearly, in Tatum's mind, the two were not mutually exclusive concepts.

"He was quick to smile, and so relaxed," Raiders fullback Mark van Eeghen told me. "Quick to giggle and laugh. Then he'd put the helmet on, and, Jesus, the switch that would turn on."

"I wanted them to know that I was in control of the field from the middle to the hashmarks," Tatum told me. "If you wanted to play in that area, you had to pay. You had to pay me. But you can't be off the field what people see on the field. That's a whole different world ... It was a different person when you take the field."

And, finally, we talked about Darryl Stingley. It had been a meaningless exhibition game in August 1978, in Oakland: Steve Grogan's pass had sailed high and behind the receiver, out of reach. As the two neared each other, Tatum lowered his head to the left, so as to avoid a head-to-head hit; Tatum's tackles had always been torso-to-torso, mano-a-mano. He had never been a head-hunter. But Stingley lowered his head, and it collided with Tatum's right shoulder. Two of his vertebrae fractured, instantly rendering him a quadriplegic.

"My shoulder pad hit him," Tatum told me, reluctant but willing to discuss the play. "It wasn't head-to-head. And, yes, it was legal." It was a horrid confluence of events, just tragic physics. After the game, Tatum went to the hospital to visit Stingley but was denied admission: "When I got there they told me only the family was allowed to come that day," Tatum told me.

Up until his death in 2007, Stingley never professed any anger at Tatum. "For me to go on and adapt to a new way of life," Stingley, who would die of complications from the injury, said in 1983, "I had to forgive him. I don't harbor any ill feelings toward him. In my heart I forgave Jack Tatum a long time ago."

It's a sentiment worth following, for The Assassin disappeared years ago. The Reverend devoted his final years to the Jack Tatum Fund for Youthful Diabetes. The legacy should encompass more than the ferocity. It should speak of the farmer, too.