The streak that changed football

It was the streak that helped build professional football.

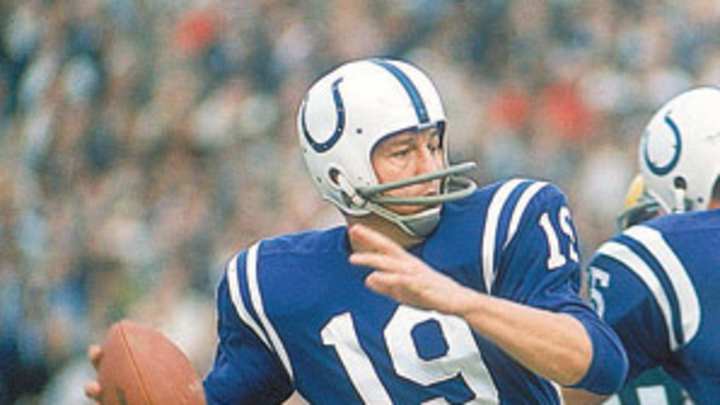

When the Baltimore Colts' Johnny Unitas started his record 47-game streak of throwing at least one touchdown pass in a game in 1956, he was an obscure quarterback playing what was barely above a niche sport.

By time the streak ended four years later, and 50 years ago Saturday, Unitas was one of the most famous personalities in the country, pro football had grown to two leagues and was sprinting past college football and even baseball in national interest.

The streak that began at high noon of the Eisenhower years and continued to the dawn of JFK's New Frontier helped make Unitas and teammates Raymond Berry, Lenny Moore, Jim Parker, Gino Marchetti, Art Donovan and coach Weeb Ewbank household names and eventually members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Unitas' record has been called the NFL's version of Joe DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak. Nearly 70 years later, however, Joe D's 56 remains an iconic number in American sports. Johnny U's streak, although appreciated by football cognoscenti, lacks the same national resonance.

One reason is that the mark never has been challenged so it's seldom mentioned by fans or commentators. Despite the pass-heavy offenses, the closest any quarterback has come to Unitas is Brett Favre's 36 straight games between 2002 and 2004. Dan Marino is the only other quarterback to hit 30.

Yes, Unitas played when there were no nickel or dime packages to frustrate quarterbacks. Zone defenses were rudimentary. But don't think it was easy.

Offensive players had very little protection from defenders. Instead of a 5-yard contact zone, a receiver could be pushed, tripped and smacked anywhere on the field until the ball was thrown. There was little protection for quarterbacks who were belted all over, including the head and face.

The Colts would win two NFL championships during Unitas' streak, including one of the most famous games in American sports history, against the New York Giants in 1958, and seemed poised to take a third entering the stretch of one of the NFL's most thrilling seasons.

The 102nd and final touchdown pass of Unitas' streak was perhaps the most spectacular of his four-year run but one that, ultimately, was overshadowed by one of the most devastating defeats in Colts history.

A new power was rising in the NFL's Western Conference, one that wore green and gold and one that would dominate the new decade.

But talk of titles and dynasties was far from the minds of a pair of rookies at the start of the '56 season. Lenny Moore was the Colts' No. 1 draft choice out of Penn State, destined to become one of football's great combination running back/receiver.

As for John Constantine Unitas, he had been cut by the Steelers in 1955 after playing college ball at Louisville. He was a sandlot legend in Pittsburgh but not much more.

Moore, who still lives in Maryland after a 12-year playing career that ended in 1967, said he was "too concerned with making the ballclub" to pay much attention to the Colts' new backup quarterback.

But Ewbank, who was in his third season as the Colts' coach, noticed something about the stoop-shouldered Unitas.

"Weeb Ewbank was the kind of coach who could see in your development where you were at," Moore said. "Weeb could see down the line; he could see that maybe it will take another season for a guy to turn the corner.

"This is what he saw in Unitas. He could see growth, he could see improvement."

When starting quarterback George Shaw was injured early in the '56 season, Ewbank didn't hesitate to go with the 23-year-old Unitas, even when his first start resulted in a 58-27 beat down from the Chicago Bears at Wrigley Field.

"When George Shaw got hurt and Johnny had to go in, Weeb said it will take some time for Johnny to develop but he's our quarterback," Moore recalled.

By season's end it was Unitas' team, although with a 5-7 record and a fourth-place finish that didn't seem to mean much. But he had thrown TD passes in his last three games, starting with a 3-yard toss to tight end Jim Mutscheller against the Los Angeles Rams in the Memorial Coliseum, the same stadium where the streak would end four years later.

Ewbank's patience began to bring dividends in 1957 as Unitas started to showcase his uncommon playcalling and leadership skills. The Colts improved to 7-5 and might have won the Western Conference title had they not blown a 27-3 lead against the eventual champion Detroit Lions or a late 21-17 lead against the pre-Lombardi Green Bay Packers.

Unitas led the NFL in touchdown passes and yards passing and earned the NEA's first-team All-Pro quarterback honor as well as its MVP award. He also threw TD passes in all 12 games.

Moore was becoming a bigger part of the passing attack as his touchdown receptions jumped from one to seven. The key, Moore learned, was staying after practice and working with Unitas and Raymond Berry, perhaps the most meticulous wide receiver in pro football history.

"Raymond told me, 'We need more of you but John won't go to you until he has confidence in you. You need to stay after practice and work with John,''' Moore said.

In 1958 all that extra work came together. Baltimore won its first six games and nine of its first 10 in running away with its first Western Conference title.

Unitas, however, was becoming a marked man. During a 56-0 rout of the Packers, Green Bay defensive back John Symank landed on Unitas' chest with both his knees. Unitas had to leave the field with three broken ribs and a punctured lung.

Despite missing two games, Unitas made nearly a half-dozen All-Pro teams as the Colts finished with a franchise-best nine wins. Again, Unitas threw touchdown passes in all 10 games he played. His streak was 25.

Unitas would throw another TD pass in '58, a 14-yard toss to Berry in the Colts' 23-17 overtime win over the New York Giants at Yankee Stadium for the NFL championship. It was called "The Greatest Game Ever Played." In two years Unitas had gone from a nobody to a star.

The 1959 season was nearly a carbon copy of '58 without the sudden death heroics. Baltimore finished 9-3 again as Unitas threw a record 32 touchdown passes. The Colts delighted a home crowd by beating the Giants 31-16 in the NFL title game.

Unitas made every first-team All-Pro squad and was voted the league's MVP. His touchdown streak was at 37, higher than any player before or since.

As the first integrated team south of the Mason-Dixon Line to win a major professional title, the Baltimore Colts had a national appeal that crossed racial and geographic barriers. They may have been the first "America's Team," although it's doubtful such hype would have appealed to the non-nonsense Unitas. He was interested in winning not nicknames.

"Johnny ran the huddle," Moore said. "Some of the guys [on the line] would say, 'John, don't call that play. This guy is beating the hell out of me.' John would say, 'What's the problem? If you can handle it will get someone else in here who can.' He ran the show and we all respected that because he knew what he was doing."

No NFL team had won three straight championships since the playoff era started in 1933 but after eight games the 1960 Colts appeared in good shape with a 6-2 record and a one-game lead over the surprising Packers.

They had survived a brutal 24-20 win in Chicago when the Bears defense pounded Unitas all afternoon, breaking his nose and bloodying his face.

With time running out, Unitas struggled to his feet and threw a 39-yard TD pass to Moore for the win. Even rowdy Bears fans seemed impressed.

One week later, however, the Colts blew a fourth-quarter lead and lost at home, 30-22, to the San Francisco 49ers">49ers as Unitas threw five interceptions. But a Green Bay loss left Baltimore in first place.

In the home finale Dec. 4 against Detroit, the Colts struggled again, trailing 13-8 in the final minute. Unitas, however, was not beaten. With eight seconds left he threw a 38-yard TD to a diving Moore who made perhaps the most spectacular catch of his Hall of Fame career. Delirious Colts fans rushed the field.

"I dove and the ball stuck," Moore said. "How I drew it into my stomach, I don't know. You can't practice things like that. It was nothing but God in charge."

The Colts were about to go 7-3, still in first place with two winnable games on the West Coast remaining. After the kickoff the Lions had the ball on their own 35 with four seconds remaining. Baltimore's secondary drifted toward the sideline, figuring Detroit would try to stop the clock.

Instead, Lions quarterback Earl Morrall, the Colts' future goat of Super Bowl III and a surprise hero of Super Bowl V, called for tight end Jim Gibbons to run down the middle of the field. Morrall hit him for a 65-yard touchdown. The Lions won, 20-15.

In George Plimpton's book Paper Lion, Morrall told the author of the utter silence that immediately descended upon Memorial Stadium.

"Slowest man on the field scores the touchdown," Moore said. "Everybody thought the game was over. All we had to do was close it out. We kind of let up and that's something you can't do. The next thing you know [Gibbons] is running down the field."

With the Packers and 49ers both winning, there was a three-way tie for first in the West. But the Colts were done.

"[That loss] took a lot out of us," Moore said.

The Colts traveled cross country to Los Angeles and played with little energy despite the presence of 75,461 fans in the Coliseum, the third largest NFL crowd that season.

Opposing a Rams team that allowed 25 points per game, the Colts managed only three points in a 10-3 loss. The game's only touchdown came on a 66-yard run by Rams quarterback Billy Wade.

The L.A. secondary, which featured Hall of Fame running back Ollie Matson who had been pressed into defensive service because of injuries, shut down Unitas. Halfback Alex Hawkins couldn't quite hold a potential TD pass in the end zone.

"It was a little behind me, but it was definitely catchable," Hawkins told Unitas biographer Tom Callahan. "John never said a word about the record. I don't think he even knew."

After 47 games, 697 completions, 10,645 yards and 102 TD passes, the great streak was over and so was the Colts' championship run.

Unitas, however, had done his part. He had helped bring professional football to a level of fan interest and media coverage that was unthinkable when the streak started. There was even a new pro league, the AFL. And he had revolutionized the position of quarterback.